The shadows behind conservatives' sunny NC jobs claims

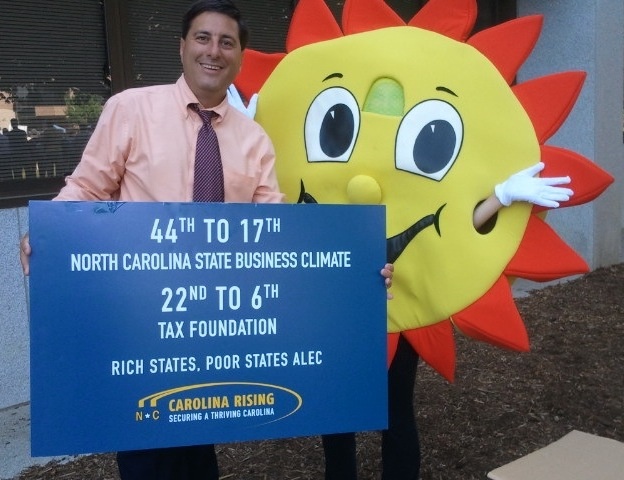

As protesters gathered outside the North Carolina legislature this week for Moral Monday, a counter-protester stood on the sidelines next to a young woman in a sun costume, handing out Sunkist sodas and yellow sun-shaped stress balls emblazoned with the cheerful message, "Jobs up, unemployment down."

The man was Dallas Woodhouse, former director of the North Carolina chapter of Americans for Prosperity, a conservative political advocacy group founded by the billionaire brothers behind the Koch Industries oil and chemical conglomerate. Woodhouse left AFP recently and now serves as president of Carolina Rising, a 501(c)(4) "social welfare" nonprofit he formed earlier this year.

The group, which is not required by law to disclose its donors, is aligned with the agenda of Republican Gov. Pat McCrory and North Carolina's Republican-controlled legislature. In his bio on the Carolina Rising website, Woodhouse touts his close relationship with McCrory, noting that in 2010 the two men worked together to block an ethics bill that would have expanded public financing of political campaigns, improved access to government records, and forbade elected officials from soliciting campaign contributions from industries they regulate.

Lately Carolina Rising has been promoting the economic policies of the governor and the legislative majority. As Woodhouse wrote in the press release announcing this week's counter-protest:

"As the protesters begin to realize the McCrory and legislative economic reforms are working these stress relievers provide these committed leftist [sic] a way to vent their frustration over being on the wrong side of the policy battles in North Carolina."

It's true that North Carolina has the nation's second-fastest-falling unemployment rate after South Carolina. Woodhouse pointed to recent jobs data that showed a drop in the unemployment rate in 99 of the state's 100 counties, which he attributed to cuts to taxes and unemployment insurance benefits.

Last year, state lawmakers and McCrory slashed the maximum weekly unemployment insurance payment by 35 percent and cut the maximum duration of benefits from 26 to 19 weeks. And by cutting weekly benefits, North Carolina was disqualified from a federally funded program to assist the long-term unemployed. Consequently, more than 100,000 North Carolinians lost their unemployment benefits sooner than they would have otherwise.

Woodhouse suggests these cuts to unemployment benefits pushed people back into the workforce. But economic experts raise questions about such claims.

In an op-ed published earlier this year in The News & Observer of Raleigh, economists John Quinterno of South by North Strategies in Chapel Hill and Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC noted that the dramatic drop in North Carolina's unemployment rate -- from 8.8 percent last June to 6.9 percent by December -- "did not come about because people rushed out and found jobs." After all, employment as measured by the household survey used to determine the jobless rate rose by only 1 percent over that period, they observed:

If people weren't finding jobs, why did the unemployment rate fall? It turns out that the legislature's prescription for lowering the unemployment rate worked through a different channel. Nearly 52,000 people were reported as "leaving the labor force" between June and December, meaning that they were no longer employed nor actively seeking work.

In fact, North Carolina ended 2013 with a labor force that had 111,000 fewer participants (-2.3 percent) than was the case a year earlier.

The decline in North Carolina's labor force has continued since then, though it has gotten smaller each month this year. An analysis released last month by the liberal NC Justice Center's Budget and Tax Center said this "suggests that unemployed workers who dropped out of the labor force in 2013 due to the lack of available job openings are starting to return to the workforce as the economy continues to slowly improve."

However, the Center's analysis also found that job growth in the state remains "anemic." At the current rate, it would take North Carolina another year to replace the 300,000 jobs lost during the recession and an additional eight years to create enough jobs to keep pace with the state's 10 percent population growth since 2007. And it would take some of the state's metro areas more than a decade to create enough jobs to return to pre-recession levels.

At the same time, the jobs that are being created are concentrated in industries that pay far less than the average state wage, the Center pointed out:

Just three industries accounted for 56 percent of the state's total job growth over the last year, and all of them paid significantly below the state's average wage of $20.40 per hour. Administrative and Waste Management accounted for 32 percent of all jobs created last year and paid just $14.83 an hour. Jobs created in Retail Trade accounted for 12 percent of the state's total employment growth and paid $12.28 per hour, while ultra-low-wage Accommodation and Food Services accounted for 13 percent of the state’s job growth and paid just $7.40 an hour.

"The last year has been a boom-time for ultra-low-wage work," said Budget and Tax Center policy analyst Allen Freyer. "As long as North Carolina keeps creating the lion's share of jobs in industries that pay poor wages, the strength of the state's long-term recovery will remain weak. A low-wage labor market simply doesn't put enough money into the hands of workers to adequately support local business growth. Low wages mean fewer customers and lower sales, which ultimately will put the brakes on hiring."

Meanwhile, North Carolina leaders are seeking further cuts to unemployment benefits. A bill introduced in the state House last month would cut the maximum number of weeks someone could receive benefits to just 14 -- the fewest in the nation. The change would apply to people who file unemployment claims after July 6.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.