In Supreme Control: What do justices owe voters in exchange for taking their cash?

By Sharon McCloskey, NC Policy Watch

By all accounts, the 2014 North Carolina Supreme Court race, with four of seven seats up for grabs, is destined for the record books.

Already spending in the race is nearing $4 million, with a little under a month to go before votes are counted.

And with public financing dollars gone, the candidates are on their own in the escalating hunt for funds.

It's a process that has experts and pundits crying for reform and leaves voters leery of a politicized judiciary parading as non-partisan.

What then to make of a Supreme Court composed of justices who act as politicians yet shield themselves from public scrutiny?

Voters expect the justices to be "fair and impartial" -- a tagline for many of their campaigns -- yet under current law, they're encouraged to behave like politicians.

They can personally solicit campaign cash, including from attorneys and firms appearing before them, and can speak at political fundraisers and affiliate with political parties.

But when it comes to questioning their biases and partiality, the process -- created by the members of the court themselves -- is as opaque as can be.

Rarely do voters, or even attorneys appearing before the justices, learn why or how a particular justice has stepped away from participating in a case.

And rarer still in North Carolina does a justice in fact take that step.

Politicized but not partisan?

Judges raising campaign dollars, particularly from attorneys and firms likely to appear before them in court, is a scenario so obviously rife with the potential for undue influence and bias that it's been banned in most places.

Thirty-nine states have some form of elections for judges, and in 30 of those judges are prohibited from personally soliciting campaign contributions.

This term the U.S. Supreme Court will consider whether such solicitation bans violate the First Amendment in Williams-Yulee v. the Florida State Bar.

But in North Carolina and eight other states, judges are free to ask for money from attorneys and law firms as well as any other member of the public. (The other states are Alabama and Texas, which hold partisan elections; Georgia, Montana, and Nevada, which like North Carolina, hold nonpartisan elections; and California, Kansas, and Maryland, which hold retention elections.)

That's been the law since 2003, when according to this report from the Brennan Center for Justice, the justices of the Supreme Court radically revised the rules of judicial conduct, without any input from the public:

North Carolina not only turned the political activity regulations on their heads -- changing the basic canon from "A judge should refrain from political activity inappropriate to his judicial office" to the current "A judge may engage in political activity consistent with his status as a public official" -- but also eliminated the Pledge or Promise Clause and the ban on candidates' personally soliciting campaign contributions.

(The Pledge or Promise Clause prohibits judicial candidates from making "pledges or promises of conduct in office other than the faithful and impartial performances of the duties of the office.")

The current judicial code of conduct allows judges to speak at political party events, personally solicit contributions, identify themselves as affiliated with a particular party and otherwise engage in activities "consistent with the judge's status as a public official."

Appearances don't matter

The 2003 revisions to the code of conduct -- which came under considerable attack from judges across North Carolina at the time, as University of North Carolina Law School professor Jon McClanahan notes in this article -- did more than just address judicial campaigning.

They eliminated an overarching and critical standard governing judicial behavior, the caution that a judge avoid the "appearance of impropriety" in all of his activities -- making North Carolina one of only two states that lack that standard.

As revised, the code states simply that a judge must "avoid impropriety" in all of his activities.

The code also sets forth some specific examples of when a judge -- if asked -- should step aside in a case.

For example, a judge should excuse himself if he has a personal bias against a party in a case, if he has a financial interest in the outcome of a case, or if he has had some personal involvement in the facts giving rise to the case.

But none specifically address situations arising from the receipt of campaign contributions -- and it is in that area, from the public's perception, that "appearances" matter.

The code does require a judge to disqualify himself whenever his "impartiality may reasonably be questioned." That determination, though, is problematic because it turns in large part upon a judge's own assessment of bias.

The "appearance of impropriety" standard, on the other hand, serves as a check on that judicial self-reflection because it incorporates the interests of those to whom elected judges are accountable -- their electorate.

Whether judges here even consider appearances anymore is unknown, given the dearth of judicial recusals in recent years and the lack of written guidance handed down by the court on the subject.

As far as can be ascertained, there have been very few, if any, recusals on the Supreme Court based upon impartiality or impropriety.

To date this year, in 28 cases that have resulted in written opinions, only Justice Cheri Beasley recused herself, four times -- most likely either because she sat on the Court of Appeals panel that heard the case below or because -- as the newest member of the court, she did not participate in hearing the case once it reached the Supreme Court. (Reasons for the recusal are not stated).

In 2013, Beasley's first full year on the court, she recused herself 31 times in the 63 cases that resulted in opinions (followed only by Justice Barbara Jackson in five cases and Justice Robin Hudson in one).

In 2012, in the 59 cases that led to opinions, only Justice Jackson recused herself, once.

And in 2011 it was all Jackson, in her first year on the court, who recused herself in 14 of 38 cases.

Flunking on recusal

So what happens when a campaign contribution raises eyebrows and calls into question a judge's impartiality?

Most often, as McClanahan notes in his review of recusals in the absence of an "appearance of impropriety" standard, parties in a case will have to ask the judge to step aside:

North Carolina Code permits a judge to recuse himself or herself "on the judge's own initiative." But there is nothing in the Code that requires -- or even encourages -- that a judge consider whether recusal is appropriate absent a motion. Given that judges overwhelmingly think of themselves as being personally immune to bias, it is unlikely that they would consider whether recusal was appropriate sua sponte.

What occurs next remains a mystery to attorneys and voters alike. Who decides whether a justice should step aside, and what standard do they apply?

The recent effort to have Justice Paul Newby recused from the redistricting case pending before the state Supreme Court illustrates just how opaque the process is.

During Newby's 2012 re-election campaign, the Republican State Leadership Committee spent millions to air the pro-Newby banjo ad.

The principal function of that group was to pave the way for Republicans in state legislatures by directing redistricting efforts -- particularly in North Carolina -- and while that ad was running on television, a legal challenge to the 2011 maps was working its way to the state Supreme Court.

The parties challenging the redistricting plan asked Newby to step aside because of the exorbitant amount of outside redistricting-related money that flooded his campaign and filed a formal motion in court.

Shortly after, without an opinion or any other guidance on the subject, the Supreme Court denied that motion. Who and how they decided and what standards were applied remain unknown.

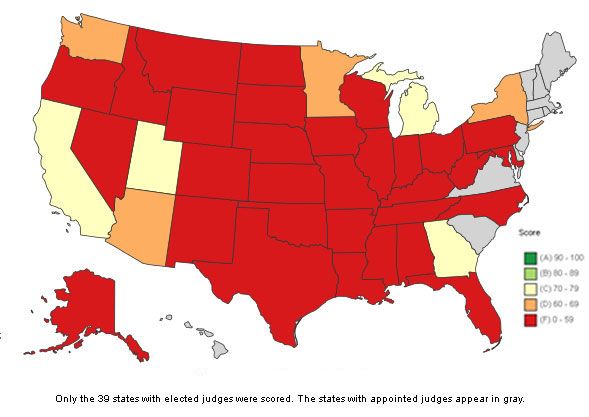

Recently, the Center for American Progress reviewed state judicial codes of conduct to see what, if any, revisions states had made in light of the increasing amount of campaign cash flooding judicial elections.

And although most states flunked the Center's test for more transparent and accountable courts, North Carolina was dead last -- sharing that spot with Wisconsin.

(Source: Center for American Progress)

Behind the curtain

The lack of guidance from the court on recusals is even more troubling when considered along with the recent changes made to judicial discipline.

In late summer 2013, pushed by the apparent lobbying efforts of Justices Mark Martin and Paul Newby, the General Assembly passed a bill that effectively allows the justices to discipline themselves behind closed doors -- including in matters related to recusals.

With the enactment of that law, North Carolina became not only one of a minority of states that have closed public hearings, but also a minority of the minority, by keeping everything closed until the Supreme Court has the final word, according to Cynthia Gray, Director of the Center for Judicial Ethics at the non-partisan American Judicature Society.

"The state judicial conduct organizations serve the pivotal function of ensuring the public that judges who abuse their power and engage in other forms of misconduct can be held accountable without political pressure," Gray said. "Trust in the efficacy of public proceedings is one of the hallmarks of American democracy in general, and public hearings for judges charged with misconduct complements the pride judges justifiably take in the openness of the judicial system in particular."

Recently at a lunch event, Justice Cheri Beasley discussed her time on the campaign trail, bemoaning -- as have most of the candidates for the state's highest court -- the time spent away from the courthouse and on the campaign trail, raising money now needed because of the disappearance of public financing.

When asked about the changes to judicial discipline in the 2013 law, Beasley noted how closely the seven justices work together and how awkward, and difficult, it would be to have to rule on one another's conduct.

And then she added: "I think the members of the public should be very concerned about those changes."

Tags

NC Policy Watch

A project of the N.C. Justice Center, N.C. Policy Watch is a news and commentary outlet dedicated to informing the public and elected officials as they debate important issues and to improving the quality of life for all North Carolinians.