We need solid ground, not an escape route

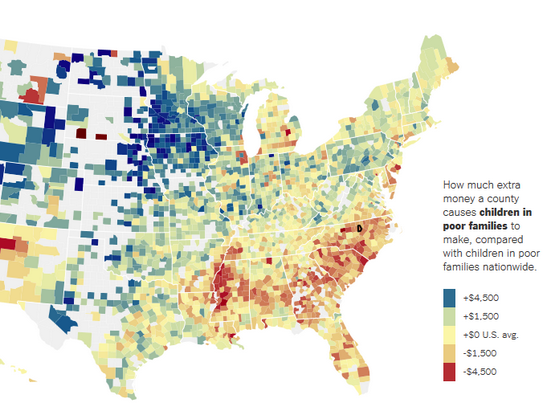

Map from The New York Times using Equality of Opportunity Project data. Click on it for a larger version. For an interactive version, click here.

By Alyson Zandt, MDC

It's your lucky day! There's new data available about inter-generational income mobility, this time at the county level. Sadly, the data show fewer lucky days for children born in the South. Once again, it's the region of the country with the lowest levels of mobility.

Twenty-five of the 100 largest U.S. counties are in the South. When the 100 largest counties are ranked by mobility, 18 Southern counties are in the bottom half of the list. The seven Southern counties that make it into the top half are all in Florida, Virginia, and Texas. A low-income child growing up in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, will earn 13.8 percent less as an adult than in a county with an average level of mobility. (We went to Charlotte to find out how leaders there are responding to low mobility.)

Data from the Equality of Opportunity Project.

The above data come from the Equality of Opportunity project. (We used one of their earlier studies on the geographic variation of mobility in the State of the South report.) Using data from Moving to Opportunity, a Department of Housing and Urban Development initiative, this new study illustrates the influence that birthplace has on a child’s income as an adult. As the NYT coverage of the study explains:

The main innovation of the new paper — part of the Equality of Opportunity Project, involving multiple researchers — is its focus on children who moved. Doing so allows the economists to ask whether the places themselves actually affect outcomes. The alternative is that, say, Baltimore happens to be home to a large number of children who would struggle no matter where they grew up.

The data suggests otherwise. The easiest way to understand the pattern may be the different effects on siblings, who have so much in common. Younger siblings who moved from a bad area to a better one earned more as adults than their older siblings who were part of the same move. The particular environment of a city really does seem to affect its residents.

The idea of comparing kids who move from a low-mobility place to a more mobile place is very useful for demonstrating the problem that the resources and infrastructure of place matter significantly for success. But the study's results don't suggest a clear solution for improving mobility at scale. Do we build escape routes for the lucky few to leave communities with low rates of mobility, or do we invest in the creation of conditions where economic success is possible, and consistently likely, everywhere? To significantly change the patterns of mobility in the South, we can't just move everyone out of high-poverty counties or neighborhoods — we have to invest in those places to improve outcomes.

While the Equality of Opportunity Project's research on the geographic variation of income mobility doesn't demonstrate causal links (meaning, they don't speculate on why a particular place has a low or high level of mobility), it does find strong correlations between five factors and the level of income mobility: economic segregation, social capital, family structure, income inequality, and school quality. Again, this doesn't necessarily mean any of these factors are causing low mobility; it's likely that the historical and economic factors that led to low mobility in a place have also contributed to disparities, like lower quality schools or concentrated poverty.

The history of a community influences its current structure; wages, occupation types, economic and racial segregation, resource allocation for public services, and wealth distribution all follow the pattern of a place's particular history of social exclusion and economic exploitation. Because of these place-specific contextual factors, many of the interventions we can make to improve economic mobility are within the sphere of control of local actors.

Southern communities must build strong place-based infrastructures of opportunity, consisting of a clear and deliberate set of pathways and supports that connect youth and young adults to educational credentials and economic opportunity. This work is already happening across the South, from Brownsville's community partnership focused on improving postsecondary success, Durham's effort to improve education-to-career pathways, and Greenville's public-private partnerships to combat intergenerational poverty. By investing in long-term, place-based efforts like these across the region, we can get closer to providing all Southern young people with a chance to thrive, regardless of race and ethnicity, gender, class, and neighborhood.