Civil rights martyr's family sends letter of encouragement to NC voting rights marchers

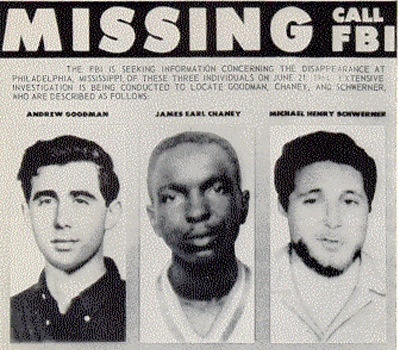

The brother of slain civil rights volunteer Andrew Goodman, seen here in this 1964 FBI missing persons poster, sent a letter of encouragement to voting rights advocates in North Carolina.

Following the opening day of the federal trial over North Carolina's restrictive voting law, as many as 6,000 voting rights supporters marched through the streets of Winston-Salem, where the trial is taking place.

The marchers gathered at a downtown plaza, where they heard from speakers including Rev. Dr. William Barber II, president of the North Carolina NAACP and architect of the Moral Monday movement, and Rev. T. Anthony Spearman, senior pastor at St. Phillip AME Zion Church in Greensboro who's been arrested several times for engaging in civil disobedience at Moral Monday protests.

Spearman read from a letter sent to Rev. Barber and the movement he leads from David Goodman, the brother of Andrew Goodman, who along with his colleagues James Chaney and Michael Schwerner was murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan while trying to register black Mississippians to vote as part of Freedom Summer in 1964.

"Please, please let us cherish the memory of Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner," Spearman said. He then read an excerpt from the letter:

Dear Brother Rev. William Barber and all those assembled on this important day,

Thank you all for your patriotic action to let all of America know that Moral Monday is here to stay as long as necessary. I am sorry that I cannot be with you. Please accept my comments as encouragement for us all.

Fifty-one years ago, on June 21, 1964, my brother Andrew Goodman and his co-workers James Chaney and Michael Schwerner were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in Neshoba County, Mississippi. Andy was just 20 years old, James was 21, and Michael was 24. These young men were investigating the burnt remains of the Mount Zion United Methodist Church, which was going to be part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer project to register African Americans to vote. In our New York City apartment a couple of weeks before he left for Mississippi, my brother Andy told me that most African Americans in Mississippi were denied [audio drops out] state-sanctioned segregationists. My brother said that was just unfair, and he wanted to do something about it. So he joined the Freedom Summer project as a volunteer.

Approximately 100 black leaders and 1,000 mostly white volunteers collectively participated in Freedom Summer 1964, one of history's most effective nonviolent social actions. Our brothers' lives were stolen because of the systemic oppression that has been with us hundreds of years before the signing of the Declaration of Independence and is still with us today. It creates a huge divide between that glorious ideal of all people are created equal, and our everyday practices. This is the dilemma that has long bedeviled America.

On June 21, 1964, at 17 years old, I became witness to the hatred that oppression engenders. It changed the course of my entire life. But the story of Goodman, Chaney, Schwerner is not my story alone. It's the story of we the people.

"We the people can never be defeated when we stay united," Spearman continued. "As I look out at our diverse faces I am extremely inspired as one who was only 13 years old when Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman were killed. Their death is etched in my memory, and I say to us today, we have to continue to move forward together, and not take one step back. Forward together!"

"Not one step back!" the crowd answered.

"Forward together!"

"Not one step back!"

You can watch Spearman read from the letter in this video. He appears at the 5:30 mark:

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.