Proceed with caution: Lessons from New Orleans' charter school takeover

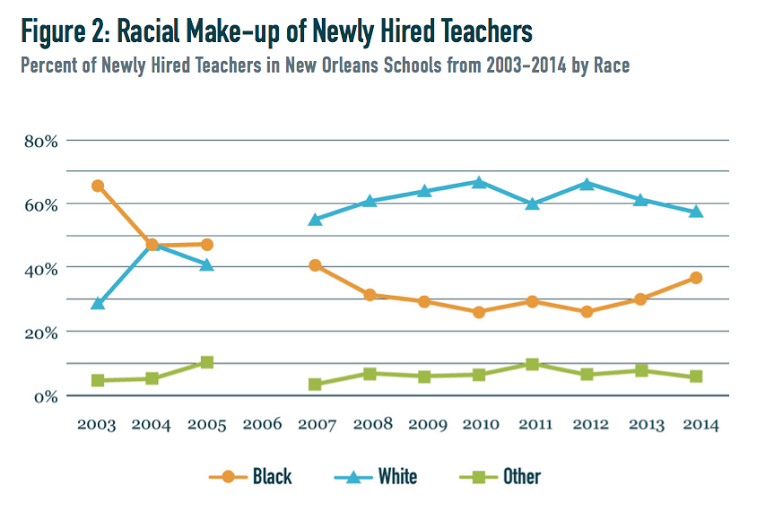

After the firing of all public school teachers and the charter school takeover in post-Katrina New Orleans, schools have hired far more white teachers even as students remain predominantly black. (Chart from "Significant Changes in the New Orleans Teacher Workforce" by the Education Research Alliance.)

Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, New Orleans did something unprecedented: The local school system fired all of its teachers and staff and converted almost all of its schools to charters. Last fall, 92 percent of the public schools in New Orleans were charters, which are publicly funded but independently managed and subject to less oversight than traditional public schools.

Since the drastic makeover in New Orleans, states such as Tennessee and Michigan have tried their own charter school takeovers with mixed results, and officials in states including Georgia and North Carolina are considering similar plans. Replicating the New Orleans model may prove difficult, as the reforms there happened under the unique circumstances of a devastating disaster. But these states have much to learn from both the successes and the failures of the New Orleans school system reforms.

After Katrina, the state legislature ordered most of New Orleans' city schools to be placed into the state-run Recovery School District, which was created two years earlier to manage the state's lowest-performing schools. Some higher-performing schools remained in the Orleans Parish School District, and most schools in both systems were converted to charters.

The academic improvements that followed were considerable. Students test scores in New Orleans have risen significantly since Katrina, though they are still lower than the state average. Researchers from Tulane University, The Data Center, and The Hechinger Report recently released a study of New Orleans public schools' transformation since 2005. It found that the percentage of students who are proficient on standardized state tests overall rose 27 percent between the 2004-2005 and 2013-2014 school years. However, the average ACT score was still below the minimum required for admission to a four-year public university in Louisiana.

The report also found higher graduation and in-state college enrollment rates for New Orleans students. The data suggest that the high school graduation rate increased by 19 percent between the 2003-2004 and 2013-2014 school years, though it dropped 5 percent in the final two years of that period. While data for out-of-state college enrollment weren't available, the study shows that the percentage of high school graduates who enrolled in in-state colleges rose 11 percent from 2004 to 2014.

The reasons for these improvements are not completely clear, as the study notes. Other factors besides the school reforms may have played a role, including increased funding, other policies aimed at helping low-scoring students such as No Child Left Behind, and the effects of students having studied elsewhere while displaced before returning to New Orleans.

But the school reforms in New Orleans have also created problems. For example, the network of independent, decentralized charter schools that has replaced the pre-Katrina system of traditional public schools has often proved inadequate for families with limited English skills. Two groups representing Asian Americans filed a federal civil rights complaint that documented sub-par English-as-a-second-language courses and a lack of interpreters for parents at school meetings.

The decentralized system has also proved problematic for special-needs students. Parents and guardians of 10 special-needs students filed a federal lawsuit, alleging physical and emotional abuse by the disjointed charter school system, which shuffled students from one school to the next and failed to provide students with needed services. A settlement was reached in February that requires schools to have an independent monitor and undergo random audits, and requires the state and the Orleans Parish School Board to pay $800,000 in the plaintiffs' legal fees and costs.

In addition, New Orleans' schools remain highly segregated, with almost three-quarters of them enrolling fewer than 10 white students in fall of 2014. White students, who make up just 6 percent of students in the city, are concentrated in very selective schools that are part of the smaller and now higher-performing Orleans Parish school system, according to the recent report.

The racial divisions extend to residents' perception of the state of the city's public schools, where 85 percent of the students are African-American. A recent poll found that two-thirds of white residents say the schools have gotten stronger since the disaster compared to only 55 percent of black residents.

The reforms also took a heavy toll on the school system's employees — and on New Orleans' black middle class. The mass firing after Katrina left 8,600 teachers and other school employees without jobs, many of whom were African-American women with extensive teaching experience. In the 2004-2005 school year, 71 percent of New Orleans' teachers were African-American; by 2013-2014 that number was down to 49 percent. Following the mass firing there was an influx of young, white, inexperienced teachers, many of them from teacher placement programs such as Teach for America and the New Teacher Project.

Tenured school employees sued for wrongful termination, but the Louisiana Supreme Court dismissed the case and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review that decision. Many of these employees were union members, but now the charter schools, unlike many traditional public school systems, don't have to engage with teachers unions, thus affording teachers fewer employment protections.

Because of the unpopular state takeover of schools and the firing of all school employees, many New Orleans citizens feel distrust toward the school system. Parents have felt shut out of the decision-making process because charter school boards, which are unelected, have sometimes violated open meetings laws and ignored recommendations of school employees and parents.

Finally, policy makers seeking to implement new charter-focused state school districts should be aware that improvements in test scores don't necessarily translate into material improvement in children's lives overall: Today's child poverty rate in New Orleans is at an astonishing 39 percent, roughly the same level as before Katrina, and 18 percent of its youth are neither working nor in school.

Tags

Alex Kotch

Alex is an investigative journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, and a reporter for the money-in-politics website Sludge. He was on staff at the Institute for Southern Studies from 2014 to 2016. Additional stories of Alex's have appeared in the International Business Times, The Nation and Vice.com.