Alabama considers a step back from prosecuting pregnant drug users

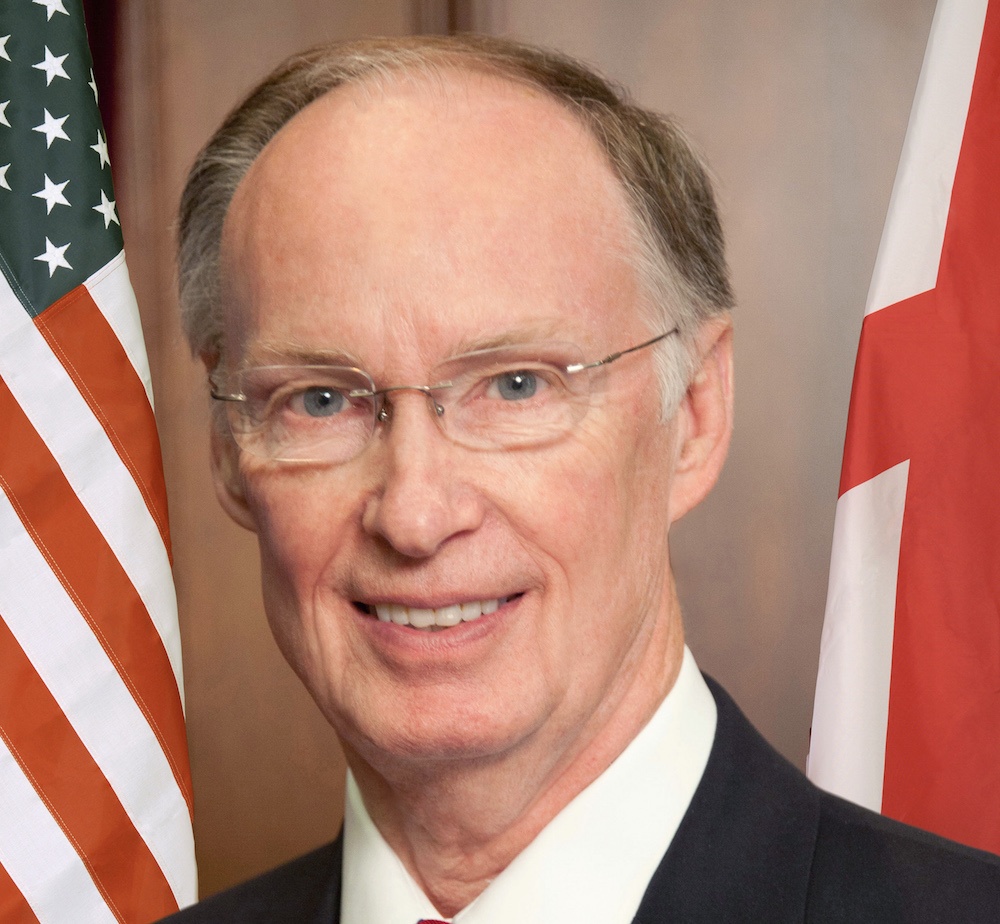

A health policy adviser to Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley (R) said his boss would ask who's in favor of a proposal to reform the state's harsh law against drug use during pregnancy before supporting it. (Photo of Bentley from the Alabama governor's website.)

By Nina Martin, ProPublica

A health task force appointed by Alabama's Republican governor is weighing proposals that could dramatically reform the nation's harshest law against drug use during pregnancy, with a draft bill expected by the beginning of the February 2016 legislative session.

ProPublica wrote about problems with the state's chemical endangerment law in September in partnership with AL.com. The law makes it a felony to "knowingly, recklessly, or intentionally" expose a child to controlled substances or drug-making chemicals. Sentences are tough: up to 10 years in prison if a child is unharmed and 99 years if a child dies.

Nearly 500 women have been arrested for pregnancy-related drug use since 2006, many turned over by hospitals that conducted legally dubious drug tests. Some have faced bails of $100,000 to $500,000, even when they had no prior record and their babies were fine.

Because chemical endangerment is considered a form of child abuse, accused mothers have lost custody of their newborns and other children. Women can even be charged if they take controlled substances such as opiate painkillers and methadone prescribed by a doctor.

Civil rights groups and public health experts have blasted the law, saying it does nothing to address the underlying problems of poverty and addiction. They say it discourages women most in need of prenatal care from getting it and burdens families with crushing fees and fines that increase economic stress and make recovery more difficult.

The proposals under discussion by a subcommittee of the Governor's Health Care Improvement Task Force take aim at some of those issues.

At a meeting of the task force Wednesday, Dr. Darlene Traffanstedt, a Birmingham-area internist who heads the subcommittee on quality of care, said her group is considering three proposals.

One would require prosecutors to offer drug treatment to pregnant women in lieu of prosecution; another would protect women who are using legally prescribed drugs. The third would return the law to its "original intent" by preventing it from being used against women for pregnancy-related drug use, Traffanstedt said.

Sara Ainsworth, director of legal advocacy for the New York–based National Advocates for Pregnant Women, which has worked to turn back laws that criminalize drug use in pregnancy, said the group was "thrilled and excited" about possible reforms in Alabama.

NAPW has fought to curb expansion of the chemical endangerment law for years without much success. The Alabama Supreme Court has twice ruled that the statute could be applied to unborn children.

In Alabama, reaction to the task force proposals was more cautious. The issue could easily be overshadowed by the group's top priority: Medicaid expansion. More than 13 percent of the state's population, and 20 percent of adults aged 18–64, are uninsured.

The chemical endangerment proposals also face likely pushback from law enforcement officials, especially any attempt to limit the law to cases where children were exposed to meth labs and other drugs after birth.

Steve Marshall, the district attorney of Marshall County in north Alabama, said the law has been a powerful tool to force pregnant women and new mothers into drug programs and to ensure that they remain clean after court-mandated treatment ends.

To qualify for drug court and diversion programs, he noted, women charged with chemical endangerment must first plead guilty. If they do well, the charges may be dropped and their records wiped clean, but they know that if they relapse, they will end up behind bars.

"Without the threat of prosecution, you have no stick," he said. "Treatment and recovery are a sustained process. You need a level of accountability."

The proposal that drug-using pregnant women be offered drug treatment in lieu of prosecution needs to be "fleshed out," Marshall said, noting that Alabama's drug abuse programs are woefully underfunded and scarce.

State Rep. Patricia Todd, a Birmingham Democrat who has been one of the chemical-endangerment law's biggest critics in the Legislature, said she favors making long-acting birth control more widely available for poor women and substance abusers.

Medicaid expansion could accomplish that, she noted, and would also provide coverage for drug treatment. "This problem [of drug use in pregnancy] is a byproduct of poverty, lack of health care, lack of good jobs, a terrible public education system," she said. "It's all tied together."

The pressure to take some kind of action is growing along with an increase in opiate and heroin-exposed newborns in the state. The number of Medicaid-covered babies born with drug-withdrawal symptoms, a condition known as neonatal abstinence syndrome, doubled in Alabama from 2010 to 2013.

Dave White, health policy adviser to Gov. Robert Bentley, said getting Marshall and the state's other 41 district attorneys on board will be key. "The governor's going to ask who's for it" before deciding whether to support any of the task force's ideas, he said.

Traffanstedt’s subcommittee "has a lot of work to do to politically smooth the way," White said, "or they're wasting their time."

The group's next meeting is in December.

Tags

ProPublica

ProPublica is an independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism in the public interest.