Special interests ramp up outside election spending, but is it working?

Super PACs, "social welfare" nonprofits, and other outside groups are spending record amounts on ads in the 2016 presidential race, more than triple the total at this point compared to four years ago. (Image from Wikipedia; layout by Alex Kotch.)

Nearly six years after the U.S. Supreme Court's Citizen United decision changed the landscape of campaign finance in the United States, political spending is skyrocketing. The decision allowed outside groups such as super PACs and "social welfare" nonprofits to receive and spend unlimited amounts of money from individuals, corporations, unions, and other political groups to influence an election as long as they do not coordinate with a candidate.

Outside groups have invested far more money at this point in the election season than ever before — and the Republican presidential primary is driving that increase.

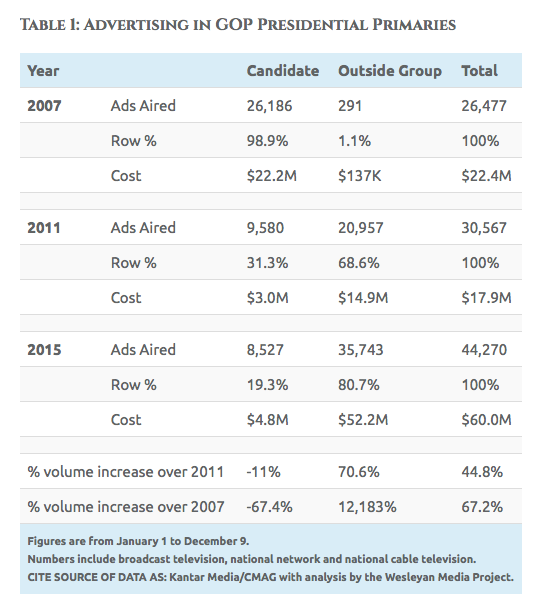

Overall spending on TV ads in the GOP primary contest, including both spending by campaigns and by outside groups, is at its highest ever this year, with $60 million spent to date, according to a recent study by the Wesleyan Media Project.* That compares to $18 million spent on TV ads for GOP candidates in 2011 and $22 million in 2007. So far this year Democratic candidates and supporting outside groups have spent just $13.4 million on TV ads.

The overall spending is being driven by outside groups. They account for 87 percent of expenditures on TV ads for the Republican presidential race, which at one point featured 17 candidates. Most of the TV spending supporting the six Democratic candidates has come from their own campaigns.

Outside groups spent more than $52 million on TV ads in the Republican presidential primary from Jan. 1 through Dec. 9. That's more than three times the $15 million outside groups spent on Republican presidential candidates at this point in 2011. So far this year, outside groups have bought more than 35,000 presidential ad spots related to the GOP primary, up 71 percent from 2011.

The dramatic change in election spending patterns becomes even more apparent looking back to 2007, before the Citizens United ruling. This year GOP presidential campaigns paid for only one-third of the ad spots they bought in 2007, while outside groups have bought 120 times more ad spots in the Republican primary this year than eight years ago.

Are the ads working?

Are the ads working?

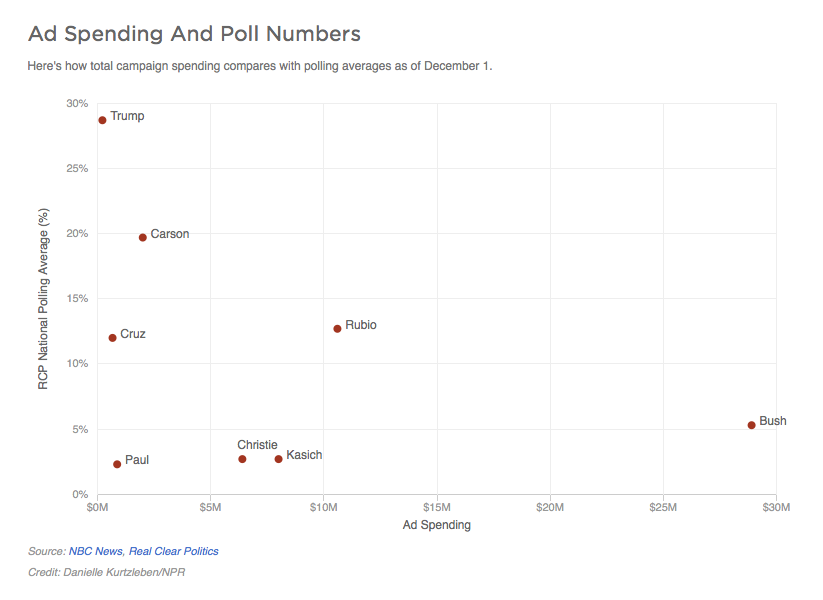

This increased spending doesn't appear to be paying off in the polls, however.

Right to Rise, the super PAC supporting Republican presidential candidate and former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, has spent $35 million on TV and radio ads since September, according to NBC News/SMG Delta.* Yet Bush's low single-digit polling average puts him at a distant fifth place in the Republican primary field. In fact, over the time this spending occurred Bush dropped 5.5 percent in the polls.

In contrast, as NBC/SMG Delta reports, no outside groups have bought ads for consistent GOP frontrunner Donald Trump, whose own campaign has spent only $217,000 on ads since September. Altogether, outside groups have spent $337,000 to support Trump, with most of that coming from a super PAC called Patriots for Trump and going toward calls, emails and mailers, according to the Sunlight Foundation.* At the same time, Trump seems to be weathering the $1.2 million spent against him by outside groups including the conservative super PAC Club for Growth Action, another super PAC supporting presidential candidate John Kasich, and the Service Employees International Union.

And while outside groups supporting the GOP presidential bid of U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas have spent just $340,000 on TV and radio since September, he's running second in the national polls.

On the Democratic side, most of the spending on behalf of frontrunners Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders is coming from their own campaigns. The super PAC supporting Clinton spent just $200,000 on TV and radio ads since September, according to NBC/SMG Delta, compared to the $11.5 million spent on ads by her campaign.

On the Democratic side, most of the spending on behalf of frontrunners Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders is coming from their own campaigns. The super PAC supporting Clinton spent just $200,000 on TV and radio ads since September, according to NBC/SMG Delta, compared to the $11.5 million spent on ads by her campaign.

Sanders has discouraged any potential super PACs from supporting him and has not seen any outside spending on his behalf. His campaign has spent $7.2 million on TV and radio ads since September.

Outside spending's mixed results

Previous elections show that outside spending is not always effective, as sometimes the candidate who attracts less outside money wins.

Consider the 2012 presidential general election. President Obama relied on considerable fundraising and spending by his own campaign ($541 million) compared to spending by outside groups ($131 million). His Republican opponent, Mitt Romney, spent less from his campaign ($336 million) but benefited from more outside spending ($419 million).

Last year, in the most expensive U.S. Senate race in history, incumbent Democrat Kay Hagan of North Carolina benefited from more outside spending ($44 million) than her Republican challenger, Thom Tillis ($33.5 million), who went on to win a tight election. (Hagan's campaign also raised and spent millions more than Tillis's.)

North Carolina state elections also show that more outside spending doesn't necessarily translate into victories at the ballot box. Outside money appears to have been a factor in some cases, such as the 2010 legislative races where groups tied to conservative businessman and mega-donor Art Pope spent more than $2.2 million on 22 key state House and Senate races, with Pope-backed candidates winning 18 of those seats. And in 2012, outside groups spent $5.5 million on behalf of winning Republican gubernatorial candidate Pat McCrory, versus $2.6 million for his Democratic opponent.

But in North Carolina's 2014 Supreme Court elections, two candidates who faced an onslaught of outside-money attacks emerged victorious. In the state race with the highest outside expenditures, incumbent justice Robin Hudson won despite benefiting from just 3 percent of the $1.3 million spent by outside groups, while incumbent justice Cheri Beasley narrowly won even though almost all of the race's $428,000 in outside spending benefited her opponent.

One possible explanation for poor returns on ad dollars is that voters increasingly don't trust political advertising.

People are "demanding authenticity and something that they think is real, and they know that advertising is not real," GOP political strategist Mark McKinnon recently told National Public Radio. "[Y]ou might as well just burn that money. It'd be a better investment."

*Expenditure figures differ among various analyses, depending on the data used. The Wesleyan Media Project uses Kantar Media/CMAG data, which tallies only TV spending, and NBC/SMG Delta data include spending on TV and radio. The Sunlight Foundation uses Federal Elections Commission data, which includes all independent expenditures.

Tags

Alex Kotch

Alex is an investigative journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, and a reporter for the money-in-politics website Sludge. He was on staff at the Institute for Southern Studies from 2014 to 2016. Additional stories of Alex's have appeared in the International Business Times, The Nation and Vice.com.