Fables of the Reconstruction: Why Clinton's comments about Southern history matter

At a CNN town hall for the Democratic presidential hopefuls this week, Hillary Clinton was asked a seemingly softball question: Who is your favorite president of all time?

Clinton's answer: Abraham Lincoln, a safe bet given Lincoln's consistent ranking among scholars as the country's best leader. But Clinton's response took an odd turn — and generated national controversy, at least among historians and pundits — when she appeared to suggest Lincoln's death was tragic not only because of the South's descent into Jim Crow and white terror, but equally disastrous because of the experiment in postwar democracy known as Reconstruction:

You know, [Lincoln] was willing to reconcile and forgive. And I don't know what our country might have been like had he not been murdered, but I bet that it might have been a little less rancorous, a little more forgiving and tolerant, that might possibly have brought people back together more quickly.

But instead, you know, we had Reconstruction, we had the re-instigation of segregation and Jim Crow. We had people in the South feeling totally discouraged and defiant. So, I really do believe he could have very well put us on a different path.

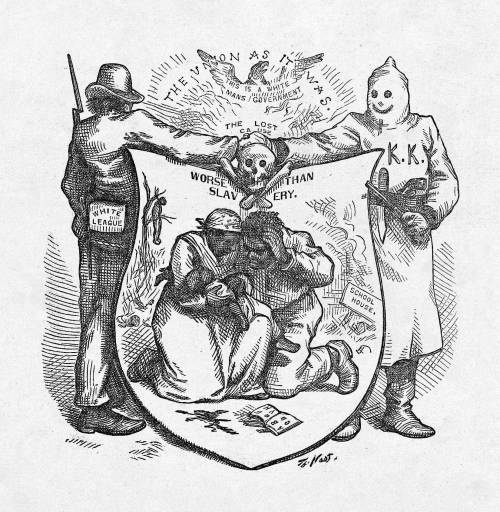

Clinton's comments seemed to revive a longstanding but now-discredited idea that Reconstruction — the period of political, economic and social upheaval after the Civil War from 1863 to 1877 — was a mistake, a period of violent and incompetent rule forced on the South by vengeful Northerners.

This view of Reconstruction, first made popular by scholars connected to Columbia professor William Archibald Dunning, took hold in the early 1900s and persisted as the dominant narrative through the 1960s. This view was challenged, most forcefully in 1935 in historian W.E.B. DuBois' classic work "Black Reconstruction," which argued that not only was Reconstruction a critical moment of progress — for example, the multiracial governments created the South's first systems of state-funded public education — but that the period's failures were largely because Reconstruction didn't go far enough.

Over time, more and more scholars chipped away at the myths of Reconstruction. Today, most of the old narrative has been disproved, including notions that the North subjected the South to military rule, that Klan violence was only a small part of the resistance to Reconstruction, and that African-American lawmakers were incompetent and corrupt — convenient fictions that were used to justify the restoration of white supremacy in the South.

But as noted by Eric Foner, author of "Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877," which is now widely viewed as the seminal book on the period, it was only after the successes of the civil rights movement — often called the Second Reconstruction — that a more accurate version of history could take hold:

The traditional or Dunning School of Reconstruction was not just an interpretation of history. It was part of the edifice of the Jim Crow System. It was an explanation for and justification of taking the right to vote away from black people on the grounds that they completely abused it during Reconstruction. It was a justification for the white South resisting outside efforts in changing race relations because of the worry of having another Reconstruction.

All of the alleged horrors of Reconstruction helped to freeze the minds of the white South in resistance to any change whatsoever. And it was only after the civil rights revolution swept away the racist underpinnings of that old view — i.e., that black people are incapable of taking part in American democracy — that you could get a new view of Reconstruction widely accepted. For a long time it was an intellectual straitjacket for much of the white South, and historians have a lot to answer for in helping to propagate a racist system in this country.

Given this background, it's no wonder that Clinton's comments, which could be read as reviving the old view that Reconstruction was the tragic result of Lincoln's assassination on par with Jim Crow itself, would ignite controversy. As Ta-Nehisi Coates — who had earlier lambasted Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders for not supporting black reparations — wrote in The Atlantic:

Yet until relatively recently, this self-serving version of history was dominant. It is almost certainly the version fed to Hillary Clinton during her school years, and possibly even as a college student. Hillary Clinton is no longer a college student. And the fact that a presidential candidate would imply that Jim Crow and Reconstruction were equal, that the era of lynching and white supremacist violence would have been prevented had that same violence not killed Lincoln, and that the violence was simply the result of rancor, the absence of a forgiving spirit, and an understandably "discouraged" South is chilling.

Clinton's campaign has since clarified her comments, issuing a statement this week that said, "Her point was that we might have gotten to a better place under Lincoln's leadership. What we needed after the Civil War was equality, justice, and reconciliation. Instead we saw the federal government abandon Reconstruction before real change took hold, which ultimately led to a disgraceful era of Jim Crow."

Whatever Clinton intended, the controversy pointed to a larger issue: The debate over Reconstruction is from over.

Reconstruction: Still a live debate

Why does the debate over Reconstruction matter today? For one, because it's a piece of our country's past that's often still misportrayed in public history, distorting our understanding of the role of slavery and race in shaping society.

The way Reconstruction is taught in textbooks has greatly improved since the days of the Dunning School's dominance. But the discredited old narrative can still be widely found. As historian James Loewen noted in a recent column in The Washington Post, a 2013 exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum on "The Civil War and American Art" claimed:

Reconstruction began as a well-intended effort to repair the obvious damage across the South as each state reentered the Union. It was an overwhelming task under ideal circumstances. Following Lincoln's assassination, that effort soon faltered, beset by corrupt politicians, well-meaning but inept administrations, speculators, and very little centralized management for programs.

In 2010, right-wing ideologues on the Texas State Board of Education generated national attention for approving a history curriculum that not only downplayed the centrality of slavery in starting the Civil War, but also the role of white terror by groups like the Ku Klux Klan in bringing an end to the South's post-war experiments in racial equality.

Last year, the debate over Confederate symbols that swept through the South brought attention to the way history is often mis-remembered in our public spaces. In South Carolina, the Confederate flag was brought down over the statehouse, but not a statue to the avowed white supremacist "Pitchfork" Ben Tillman, who led paramilitary Red Shirts in violently opposing Reconstruction, voiced sympathy for black lynchings and ushered in the Jim Crow era during his time as governor and U.S. Senator from 1890 to 1918.

In the South, the first and second Reconstruction eras still serve as a source of inspiration and a framework for those working for a more equitable and just future.

In the early 2000s, at the Institute for Southern Studies we began discussing the concept of a "Third Reconstruction" to grapple with the persistent barriers to economic, racial and political equality in the South. Around the same time, scholars and organizers connected with the Industrial Areas Foundation launched a Third Reconstruction Institute to discuss the theory and practice of, in the words of co-convener Romand Coles, a "radical democratic" vision for change.

More recently, Rev. William Barber II, leader of the North Carolina NAACP and the state's Moral Monday movement, has used the idea of a "Third Reconstruction" as a framework for a vision of a multiracial movement for justice in the South, detailed in his recent book by the same name. In "The Third Reconstruction," Barber recounts the swelling Moral Monday protests in North Carolina in 2013, and coming back to the state after attending the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington:

I came home to the beginnings of a Third Reconstruction. After America's First Reconstruction was attacked by the lynch mobs of white supremacists in the 1870s, it took nearly a hundred years for a Second Reconstruction to emerge in the civil rights movement. Though we ended Jim Crow segregation in the 1960s, structural inequality became more sophisticated in the backlash against the movement's advances. We have a black man in the White House that was built by slaves, but the wealth divide that is rooted in our history of race-based slavery is more extreme than it ever has been. Nothing less than a Third Reconstruction holds the promise of healing our nation's wounds and birthing a better future for all.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.