Lawyers pour money into N.C. Supreme Court race, raising conflict-of-interest concerns

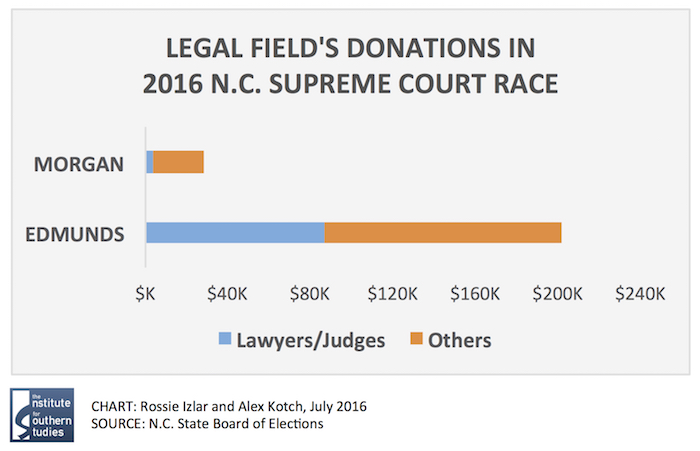

North Carolina's high court race is drawing intense interest from the legal profession. Lawyers who could have business before the court have contributed almost half of Republican incumbent Justice Bob Edmunds' (right) campaign funds while sending a smaller amount to Democratic challenger Mike Morgan (left). (Images from candidates' campaign websites.)

Starting in 2004, most state Supreme Court candidates in North Carolina used an acclaimed public financing program under which they raised a number of small contributions to become eligible for a grant to run their campaigns. Since the Republican-led state legislature killed the program in 2013, candidates have had to rely more on big-money fundraising and help from outside spending groups.

In 2012, with the public financing program still in place, high court candidates raised $80,000 on average. In 2014, with that program gone and the contribution limit raised by lawmakers from $1,000 to $5,000, the average amount raised was about $500,000. Much of that money came from lawyers with potential business before the court, raising conflict-of-interest concerns.

In this year's race for an open seat that could shift the court's ideological balance, lawyers continue to donate heavily. To date, incumbent Justice Bob Edmunds, a registered Republican, has taken in a much higher percentage of money from the legal field than his Democratic opponent, Superior Court Judge Mike Morgan.

From the beginning of 2015 through June 30 of this year, Edmunds' campaign has raised over $200,000 from individuals and political action committees, excluding donations from him and his wife. According to a Facing South analysis of state elections data, lawyers and judges have contributed over 43 percent of Edmunds' total. Morgan, who joined the race only a few months ago, raised close to $25,000, excluding donations from him and his family, with less than 16 percent of that coming from attorneys. Partners and other attorneys who have taken cases to the N.C. Supreme Court have contributed to Edmunds' campaign. A few examples:

Partners and other attorneys who have taken cases to the N.C. Supreme Court have contributed to Edmunds' campaign. A few examples:

* Thomas Farr of Ogletree Deakins, who successfully defended the state's controversial 2011 redistricting maps against racial discrimination claims, gave $1,000.

* Tharrington Smith's Michael Crowell gave $500 in May. A month earlier, he argued for the plaintiff who successfully challenged the legislature's recent move to retention elections for the N.C. Supreme Court — a verdict that decreased re-election odds for Edmunds, who recused himself from the case. Two other Tharrington Smith attorneys added $400 total.

* Paul Hendrick and Matthew Bryant each gave $300. The partners at Hendrick Bryant Nerhood Sanders & Otis argued on behalf of plaintiffs in an important eminent domain case in which the N.C. Supreme Court upheld a lower court's ruling that the state must pay landowners whose properties lie in the path of a future state beltway.

* John Culver, a partner at K&L Gates, donated $200. He argued before the N.C. Supreme Court last year on behalf of House Speaker Tim Moore and Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger, in a case over control of appointments to the Coal Ash Management Commission. K&L Gates partner Eugene Pridgen gave another $250.

Of Morgan's 258 donations, 18 came from attorneys. They include a $100 donation from attorney Chandra Taylor of the Southern Environmental Law Center, which has argued on behalf of environmental groups at the court.

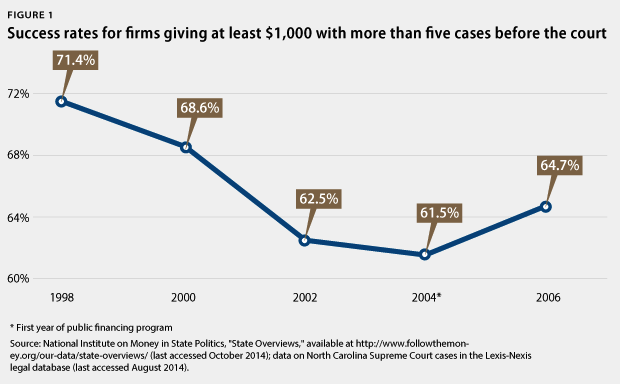

Research suggests a connection between attorneys' contributions to judicial candidates and case outcomes.

According to a 2014 study by the Center for American Progress, law firms that gave at least $1,000 to N.C. Supreme Court candidates and had more than five cases before the court had higher success rates than firms that gave less than $1,000. But after the state launched its public financing program, the correlation between donations and wins weakened, raising questions about judicial impartiality in a campaign system dependent on special-interest money. The following chart is from that study: Further heightening concerns about impartiality, North Carolina ranks last in the nation in judicial recusal rates.

Further heightening concerns about impartiality, North Carolina ranks last in the nation in judicial recusal rates.

Among the other findings of Facing South's analysis of spending in the Edmunds-Morgan race:

* Contributions from corporate executives make up over 14 percent of the Edmunds campaign's large donations — $50 or more — compared to under 4 percent of Morgan's. Edmunds' contributors include executives with tobacco giant Reynolds American and CaptiveAire Systems, who are also major donors to state and federal races.

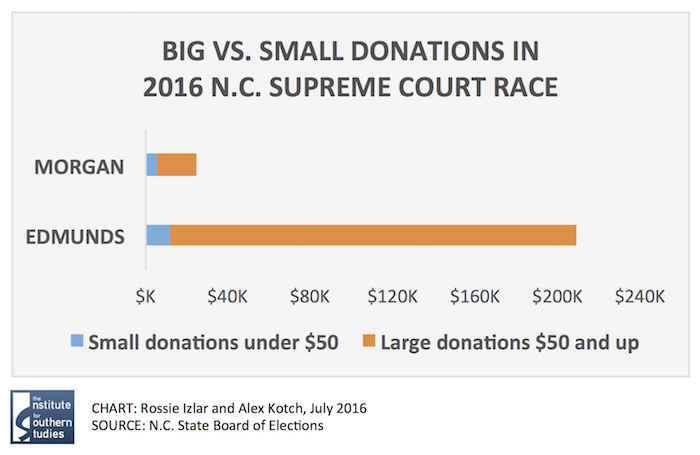

* Almost 21 percent of the money raised by Morgan has come in the form of small donations of $50 or less compared to less than 6 percent for Edmunds. Fifty-seven percent of Morgan's individual donation amounts were small versus less than 16 percent for Edmunds. Outside money is expected to be another factor in the race, and in fact it has already played a major role. A political spending group representing business interests spent $450,000 on an ad supporting Edmunds in the primary. The N.C. Chamber of Commerce made the buy, which was financed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Judicial Crisis Network, a group that has challenged President Obama's U.S. Supreme Court nominees and is now spending heavily on state supreme court races.

Outside money is expected to be another factor in the race, and in fact it has already played a major role. A political spending group representing business interests spent $450,000 on an ad supporting Edmunds in the primary. The N.C. Chamber of Commerce made the buy, which was financed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Judicial Crisis Network, a group that has challenged President Obama's U.S. Supreme Court nominees and is now spending heavily on state supreme court races.

In 2014, outside spending in four N.C. Supreme Court races topped $1.8 million, much of it originating from the Washington, D.C.-based Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC), which is funded mostly by corporations including North Carolina-based Duke Energy, Reynolds American and Variety Stores.

Two years earlier, the RSLC channeled close to $1.2 million to state-based groups that spent in support of Justice Paul Newby in a race where total outside spending exceeded $2.5 million. Newby won.

Institute intern Rossie Izlar contributed research for this report.

Tags

Alex Kotch

Alex is an investigative journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, and a reporter for the money-in-politics website Sludge. He was on staff at the Institute for Southern Studies from 2014 to 2016. Additional stories of Alex's have appeared in the International Business Times, The Nation and Vice.com.