The group behind Confederate monuments also built a memorial to the Klan

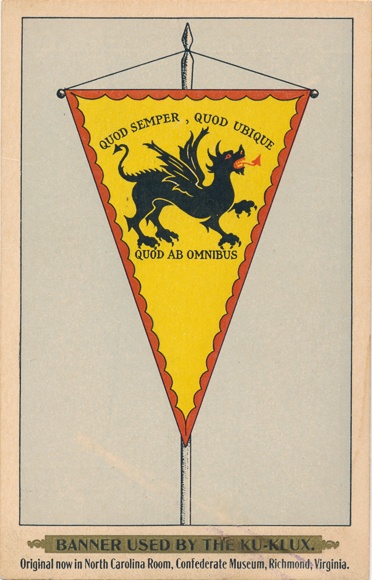

The North Carolina Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy printed postcards bearing the image of a Ku Klux Klan flag to raise funds to purchase the banner for display in the North Carolina Room of the Museum of the Confederacy (now the American Civil War Museum) in Richmond, Virginia. The UDC venerated the Klan and elevated it to near-mythic status. (Image from Alexander Historical Auctions used with permission.)

It was a Saturday. The mailman never comes to my door, but there was his knock. A couple days earlier I had ordered a book on Amazon that I had seen before only in a library. "Sorry to bother you," he said, "but I had to have you sign for this one." The return address on the padded manila envelope was a post office box in Charlotte, North Carolina. No name.

I cut the shipping tape and carefully pulled out the contents, wrapped inside a grocery bag. The worn 1941 first edition of Mrs. S.L. Smith's "North Carolina's Confederate Monuments and Memorials" — one of the only compilations by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) itself, written by the historian of the North Carolina Division — had a new home.

And on page 35, there it was, the answer to my question: Did the UDC — a group responsible for most of the Confederate monuments roiling communities today, and that still promotes itself as "historical, educational, benevolent, memorial and patriotic" — erect a monument to a white-supremacist terrorist group?

IN COMMEMORATION OF THE "KU KLUX KLAN" DURING THE RECONSTRUCTION PERIOD FOLLOWING THE "WAR BETWEEN THE STATES" THIS MARKER IS PLACED ON THEIR ASSEMBLY GROUND. THE ORIGINAL BANNER (AS ABOVE) WAS MADE IN CABARRUS COUNTY.

ERECTED BY THE DODSON-RAMSEUR CHAPTER OF THE UNITED DAUGHTERS OF THE CONFEDERACY. 1926

The answer was yes. Sixty-one years after the end of the Civil War, the UDC constructed a memorial to the Ku Klux Klan outside of the city of Concord, North Carolina.

* * *

Horrible things never stay dead. Sometimes they never die at all. They just lurk under the surface of everyday politeness, eroding the foundation of decency and equity we like to think we have built our world upon. And sometimes, all it takes is one event for the ugliness to erupt like a geyser of bile. That seems to be our world these days. One geyser after another. Fake news, bots, internet trolls, propaganda. Blatant falsehoods presented as truths.

The ugliness isn't really new, though. Only the medium and volume have changed.

Consider the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The Richmond, Virginia-based group is best known for erecting monuments to Confederate veterans, but its influence on American history is far more pervasive. Every time a Confederate monument controversy erupts, someone asks, "Were the monuments meant to be racist?" The short answer is "yes." But the monuments are just single trees in a larger forest. We have to step back and see the forest — and consider who planted it — to fully appreciate what the UDC was able to accomplish in an age before television and the internet.

Immediately after the Civil War, federal troops occupied the South. Newly freed blacks began to hold political office, start businesses, buy property, and go to school. White Southerners violently chafed under the racial role reversal in the era that came to be known, with deep-seated anger, as Reconstruction. The Ku Klux Klan ruled the night. With an abundance of white men with military training sitting about, recruits were easy to come by.

When federal troops ended their occupation in the late 1870s, the festering ugliness burst to the surface. In North Carolina and across the South, whites used violence to remove blacks from office, rig elections, intimidate voters at polling places, destroy black businesses and farms. Whites took control again. The new white-dominated legislatures began passing literacy requirements and property requirements for voting, imposing poll taxes, and institutionalizing racial segregation. Thus began the "Jim Crow" era in the South.

It was against this backdrop that the UDC flourished, eventually growing to almost 100,000** members nationwide and gaining an astounding amount of political power for a women's organization in a time when women could not even vote.

The UDC was organized in 1894 in Tennessee by a group of daughters* of affluent and influential Confederate veterans. While the UDC singlehandedly created a social safety net for Confederate veterans and their families, built veterans homes and hospitals, and engaged in historic preservation, the group also had another agenda. They and leaders of associated organizations like the Confederate Veterans realized that, with the military battles over, they would have to wage a long-term struggle for hearts and minds to solidify white control of the South. It would be a war of ideas.

To that end, the UDC launched a long-term campaign to re-write the history of the Civil War, the South, and the country. By building monuments to the Confederacy and gaining control of school curricula, the Daughters spread a false history aimed at perpetuating the culture and ideals of the Civil War-era South, a society built on white supremacy. And they were remarkably successful.

Their delivery vehicle was the "Lost Cause" ideology, which promoted broad, romanticized, largely fictional assertions designed to absolve the South from any blame in the Civil War and to vindicate the Southern cause. It was pure propaganda. Its core assertions:

- States rights (usually, the right to secede) and not slavery were the cause of the Civil War.

- Slaves were content and happy and not mistreated in slavery. In fact, they benefitted from slavery.

- Confederate soldiers were heroic, mythical figures to be revered for defending the South and its way of life.

Although never named as its goal, white supremacy underpins the entire "Lost Cause" ideology. To focus only on one part, like the monument building, means missing the forest for the trees.

* * *

The UDC and "Lost Cause" monument building spread like wildfire in the Jim Crow era. By 1897, the UDC was in my home state of North Carolina.

The North Carolina Division's original constitution did not explicitly restrict membership to white women, though it effectively did so by requiring that members be direct descendants of Confederate veterans or governmental officials.

But in 1903, the N.C. Division amended its constitution to add a racial requirement that limited membership to white women. And to further sift what it considered to be the wheat from the chaff, many state divisions required that a would-be-member had to be approved by a certain number of other members, which really meant you had to be from the upper crust of Southern society. The UDC wanted your familial and social connections.

An example of an acceptable member was Mrs. I.W. Faison, an officer in the N.C. Division who would eventually become its president. The wife of a prominent Charlotte physician, she was associated with various innocuous women's auxiliary groups, charities and garden clubs — as well as a number of white supremacist organizations in Mecklenburg County, including the bluntly named White Supremacy Club. Her husband, Dr. Isaac Faison, was president of the North Carolina Medical Journal, dean of the medical school that was established at Davidson College for a time, and a close, lifelong friend of Zebulon Vance, the Confederate governor of North Carolina. Prominence and connections mattered.

Politicians loved the UDC. Members were voracious fundraisers. As women, UDC members could not vote, but their husbands could. And given their prominence in the community, UDC members could influence other people's vote.

It was Mrs. Faison who, as president of the North Carolina UDC at its 13th annual convention in 1909, summarized the group's purpose and who it was intended to benefit:

The work of the United Daughters of the Confederacy is not based on sentiment alone, as the records of our work will show. Our main objects are memorial, historical, benevolent, educational and social. We are building monuments of bronze and marble to our noble Confederate dead as an inspiration to future generations. We have built and assisted in building all over the South, monuments in the form of Soldiers Homes, Hospitals, Memorial Halls and Schools for descendants of our Confederate soldiers, in whose veins flow pure Anglo Saxon blood, who otherwise could not be educated.

UDC members frequently use the term "Anglo-Saxon" in their discussion of Confederate soldiers and monuments. In 19th century America, "Anglo-Saxonism" was white supremacy with added conceptual elements. According to Karen Cox, history professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and author of "Dixie's Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture," it celebrates white heroes, mythical or otherwise, and promotes the belief in the superiority of so-called "white civilization."

Some North Carolina UDC members were more explicit in their rhetorical embrace of white supremacy. Consider the declaration of Lucy Closs Parker, president of the Vance County chapter, at the third annual N.C. Division convention in 1899:

The old Confederate soldier looks down from the sky and laughs as he sees the principles for which he fought established, the great battle for the Constitution, State's rights, white supremacy, all the South has conquered.

Parker, in fairness, was quoting the chapter chaplain's opening prayer. But the statement left no room for confusion regarding the racial motivations of the N.C. Division. Their choice of keynote convention and event speakers also made clear their white-supremacist views and motives.

At the group's 14th annual convention in 1910, the welcoming speaker was Joseph B. Ramsey, an affluent lawyer, Rocky Mount city council member, and president of First National Bank of Rocky Mount who would go on to serve as president of the North Carolina Banker's Association, as well as the city's mayor. Ramsey openly praised the UDC's commitment to white supremacy:

You were the song of the Old South: you are the theme of the New South; and to-day in this high hour of peace and commercialism, when men are prone to forget, we find you banded together, United Daughters of the Confederacy, all still loyal to Southern rights, democracy, and, thank God, to white supremacy.

At an address to the UDC and Confederate Veterans in Wadesboro, North Carolina, in August 1903, W.M. Hammond, a former Confederate officer and the keynote speaker, railed against Reconstruction:

They [the North] promoted ignorance over learning, and set brutality and lust to keep rule over innocence and virtue. They wrote negro suffrage and negro equality with bayonets in the code of every Southern State. They ravished the Federal Constitution and wrote it there. They laid interdict after interdict on white supremacy and white control. As well might they have laid an interdict "on seas and worlds to chain them in from wandering."

This sort of thing continued well into the 1930s. In 1933, for instance, Justice Heriot Clarkson of the North Carolina Supreme Court addressed a UDC-sponsored Confederate Memorial Day event in Raleigh. As a politician, Clarkson had been instrumental in gaining and maintaining white rule in North Carolina. Railing against Reconstruction was his raison d'etre, as was promoting segregation and black voter suppression.

Clarkson lashed out against the North setting "millions of negro slaves" loose in the South to subjugate the white man. He blamed the North for slavery. In stunning irony, Clarkson said the suffering of the white Southerner under Reconstruction was far greater than the black in slavery. "The vanquished patriots and their children became the hirelings of the conquerors," as he put it. "No race or people on this earth suffered more." Blacks, he said, were a "barbarous race" that Southern whites had the burden to "civilize and Christianize."

Clarkson wasn't done. He then went on to cite "A Fool's Errand" by Albion Tourgée, the tale of a Northerner who came to the South after the war to help rebuild the South and integrate blacks. A bestseller in 1890s, it was based in part on the life of Tourgée, a lawyer who had come to North Carolina after the war and was active in Reconstruction politics. He eventually left the state disheartened that the federal government would not do more to help blacks. But the book is work of fiction. Nevertheless, "A Fool's Errand" became a favorite of the Ku Klux Klan, which often misrepresented it as fact. Clarkson took the opportunity to do the same.

"He [Tourgée] was one of those who undertook to change the law of God and nature by trying to make an inferior negro race dominate the white race."

Foreshadowing the segregation-forever arguments of white Southern politicians in the Civil Rights era, Clarkson said:

No man or set of men, be they cloistered clergy or laymen, lacking common sense, are justified, in trying to change the natural law. Each race should take pride in its purity and integrity. Separation and segregation with justice has ever been and ever will be the policy of the South as it is founded on the immutable law of God and nature, and be it to the glory of North Carolina that this commonwealth is doing justice to the negro.

Clarkson continued:

When the Anglo-Saxon Confederate Soldiers and the women of the South, and their sons and daughter after years of humiliation, sacrifice and struggle, regained the Government founded on "White Supremacy through white men," these foreign political leaches fled the State like rats out of a sinking ship. In North Carolina, this struggle of white supremacy lasted off and on until the "White Supremacy" General Assembly of 1899.

When we look back at the crucifixion of the South, let us try to forgive and forget. It was the Master on the cross who said "Father forgive them, for they know not what they do." I come now to the turning point in this Commonwealth, when the Anglo-Saxon race gained supremacy in 1899.

1898 was a seminal year in North Carolina racial politics. It was the year of the violent white overthrow of the black-led municipal government in Wilmington, then North Carolina's largest city. The coup was viewed as a horror in the North and a victory and battle cry in the South, and it foreshadowed whites' taking control of the state legislature in 1899. This is what Clarkson was talking about.

Declarations of white supremacy at UDC events were not an exception but regular occurrences. Monument dedications drew massive white crowds; for example, 15,000 to 20,000 people attended a 1907 dedication in Newton, North Carolina. Dedication pageantry was highly scripted. Banners of red and white, the colors of the Confederacy, and the Confederacy's four flags would festoon the town. An elaborate processional would parade into the square, complete with white children dressed all in white in neat lines following the UDC members and Confederate veterans. Little girls in white dresses and red ribbons lined the streets. Often, 13 young women in white and red, representing the 13 states of the Confederacy, surrounded the monument itself as the dedication speaker addressed the gathering. Monument dedications were milestone events for communities that would be remembered for decades. There would be no better venue to send a racially charged message to the populace. And politicians and business leaders often obliged.

In 1909, Gov. William Kitchin spoke at the dedication of the Granville Grays monument in Oxford, North Carolina. He declared that whites and blacks would never be equal and that no army or constitution would ever make them so. He said that the Ku Klux Klan was necessary to keep order, and that whites had dominated every race they ever encountered and always would.

Then in 1913, one of the most famous white supremacist diatribes at a UDC monument event was loosed by Julian S. Carr, the Confederate general, North Carolina industrialist, and renowned white supremacist, at the dedication of "Silent Sam" on the campus of UNC Chapel Hill:

The present generation, I am persuaded, scarcely takes note of what the Confederate soldier meant to the welfare of the Anglo-Saxon race during the four years immediately succeeding the war, when, the facts are, that their courage and steadfastness saved the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the South — when "the bottom rail was on top" all over the Southern States, and to-day, as a consequence, the purest strain of the Anglo-Saxon is to be found in the 13 Southern states — Praise God.

I trust I may be pardoned for one allusion, howbeit it is rather personal. One hundred yards from where we stand, less than ninety days perhaps after my return from Appomattox, I horse whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection in these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterwards slept with a double-barrel shot gun under my head.

* * *

On the national level, the United Daughters of the Confederacy were every bit as open and blunt about their embrace of white supremacy as the N.C. Division.

At their national convention in 1901, the UDC adopted a motto that pledged to educate the descendants of "the men who wore the grey … and thereby fasten more securely the rights and privileges of citizenship upon a pure Anglo-Saxon race."

At a speech in Washington, D.C., in 1912, Mildred Lewis Rutherford, the Georgia-born historian general for the national UDC, stated the group's view of Reconstruction in the South:

It is true, he [white men] had to fight his way with shackled hands during the awful reconstruction period; but wise men of the North understand why it was a necessity then. He [white men] were compelled to establish the political supremacy of the white man in the South. (Applause). So too, the Ku Klux Klan was a necessity at that time, and there can come no reproach to the men of the South for resorting to that expedient.

Rutherford's opinion of the black race was unequivocal. Consider her discussion of slavery in a 1916 speech in Dallas, Texas:

The South was giving to the negro the best possible education — that education that fitted him for the workshop, the field, the church, the kitchen, the nursery, the home. This was an education that taught the negro self-control, obedience and perseverance — yes, taught him to realize his weaknesses and how to grow stronger for the battle of life. The institution of slavery as it was in the South, so far from degrading the negro, was fast elevating him above his nature and his race.

And what did Rutherford see as the nature of the black race? As she explained in a 1914 address in Savannah, Georgia:

What was the condition of the Africans when brought to this country? Savage to the last degree, climbing coconut trees to get food, without thought of clothes to cover their bodies, and sometimes as cannibals, and all bowing down to fetishes — sticks and stones — as acts of worship.

Then in typical Lost Cause fashion, Rutherford claimed biblical justification for slavery:

More negros were brought to a knowledge of God and their Savior under this institution of slavery in the South than under any other missionary enterprise in the same length of time. Really more were Christianized in the 246 years of slavery than in the more than thousand years before.

And she didn't stop:

The negro race should give thanks daily that they and their children are not today where their ancestors were before they came into bondage.

Was the negro happy under the institution of slavery? They were the happiest set of people on the face of the globe-free from care or thought of food, clothes, home, or religious privileges. ...

I am not here to defend slavery. I would not have it back, if I could, but I do say I rejoice that my father was a slaveholder, and my grandfathers and great-grandfathers were slaveholders, and had a part in the greatest missionary and educational endeavors this world has ever known.

Rutherford was arguably the most influential voice in the UDC for decades, and she was highly sought after as a speaker and writer in the post-Reconstruction South. Her views were almost gospel in the UDC. But she wasn't the only prominent UDC member with white supremacist views.

Take the case of Rebecca Latimer Felton, who addressed the national UDC convention in 1897. Felton was one of the most influential women in Georgia and a renowned white supremacist. Her prime concern was making sure that white women bore only white children (i.e., no relations with black men).

"The destiny of the white population rests in their hands," she said. "They will make or unmake the progress of their own race and color…" Interestingly, Felton thought the UDC was putting too much time and money into monument building and not enough time and money into schools and education efforts for the children and families of veterans, which made her an outlier of sorts in the UDC. She campaigned tirelessly for such funding.

* * *

Perhaps nothing illuminates the UDC's true nature more than its relationship with the Ku Klux Klan. Many commentators have said the UDC simply supported the Klan. That is not true. The UDC during Jim Crow venerated the Klan and elevated it to a nearly mythical status. It dealt in and preserved Klan artifacts and symbology. It even served as a sort of public relations agency for the terrorist group.

At the ninth annual N.C. UDC convention held in Morganton in 1905, Lucy Closs Parker announced that an original Ku Klux Klan flag from Cabarrus County was being offered for sale. The Klan went through several incarnations in the South, and the UDC considered sacred anything from the first phase in 1870s and 1880s. The UDC's N.C. Division had gotten into a fervent bidding war for the flag with divisions from other states. It asked local chapters to pledge to the effort, and most halted other fundraising initiatives so they could concentrate on the flag purchase.

Parker noted that there was deep desire in the N.C. Division to procure the Klan flag for display in the North Carolina Room in the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia. Apparently, a number of UDC members had family in the Klan. One UDC member told Parker that five of her family members were in the Klan — her husband and four brothers. Getting the flag became an urgent priority.

By 1906, the N.C. UDC had closed the purchase for what amounted to $1,318 in today's dollars. Parker, by that time the director of the North Carolina Room, announced the purchase at the group's 10th annual convention in Durham. The flag was sent to Richmond. Hundreds of commemorative postcards were printed and sold depicting the banner. As late as 1915, the N.C. UDC continued to sell the Klan postcards to the public. Today, the flag resides in The American Civil War Museum in Richmond.

In another instance, the N.C. UDC commissioned a portrait of Randolph Shotwell (for over $2,300 in 2018 dollars) to hang in the North Carolina Room. Shotwell was a Confederate veteran, newspaper editor, and the self-confessed leader of the Ku Klux Klan in a large section of western North Carolina. He went to federal prison for his Klan activity during Reconstruction. The Klan in North Carolina was fiercely loyal to Shotwell, who they revered and considered a martyr to the cause. Shotwell was also revered by the North Carolina UDC.

The Shotwell portrait was dedicated at the UDC's 1909 N.C. Division convention. The dedication speaker was Capt. Walter Taylor, a Confederate veteran and Ku Klux Klan leader who took the convention podium fully robed and hooded in formal Klan regalia. Taylor even had his own Klan attendant present to pull back his hood in ceremonial fashion; the attendant was married to an active UDC member. Taylor's dedication speech was an excoriation of Reconstruction, black suffrage, and racial equality, and a defense of the actions of the Klan and those that opposed Reconstruction. He gave a long discourse on the Tourgée book, and he roared that when Shotwell was arrested he was "slapped with the white palms of black hands."

In accepting the portrait for the UDC, Mrs. Eugene Little, chairperson of the North Carolina Room, compared the Pope's beatification of Joan of Arc as a saint to the UDC's own beatification of Shotwell.

When Shotwell got out of federal prison, he was elected to the North Carolina legislature and eventually became the state auditor.

While there was already a monument to Shotwell at his grave in the Confederate Cemetery in Raleigh, Mrs. Faison, the president, issued the plea for a separate NC Division monument to Shotwell at the 12th Annual Convention:

Your President cannot bring this lengthly report to a close without making a plea for the Randolph Shotwell Monument. If there ever was a man who deserved a monument to his memory this is the one. During the trying days of the "Ku Klux" he was a leader and suffered much for the good of the South He always stood firm and wavered not in his love for and allegiance to his people, for what he knew to be right.

Today the Shotwell portrait resides at the American Civil War Museum, the renamed Museum of the Confederacy.

The national UDC also embraced the Klan. Let's circle back to UDC historian Mildred Lewis Rutherford, who viewed the Klan as a counterpart to the federal agency that helped formerly enslaved people after the Civil War. Speaking in 1915 to the UDC national convention in San Francisco, she said:

The North said the Freedman's Bureau was necessary to protect the negro. The South said that the Ku Klux Klan was necessary to protect the white woman.

The trouble arose from interference on the part of the scalawags and carpetbaggers in our midst and they were ones to be dealt with first to keep the negros in their rightful place.

And in a 1912 address to the UDC's national convention in New Orleans, Rutherford endorsed the notion that the South is "a white man's country":

The Ku Klux Klan was an absolute necessity in the South at this time [Reconstruction]. This Order was not composed of the "riff raff" as has been represented in history, but of the very flower of Southern manhood. The chivalry of the South demanded protection for the women and children of the South.

Justification and veneration of the Klan aside, this is a rather telling statement. It expresses a truth that some Southerners of my own generation may only now be willing to admit: When a white person in the South says "South" or "Southern" or "Southerner," they are not necessarily talking about everybody. They are usually talking about whites. In this way of thinking, black people are not part of the South. This was certainly true in the Jim Crow era.

This notion of black Southerners as "other" was promulgated by the UDC. At its national convention in New Orleans in 1913, the UDC unanimously endorsed a book titled "The Ku Klux Klan or Invisible Empire" by UDC member Mrs. S.E.F. Rose. The book is a highly revisionist version of the history of the Klan and Reconstruction. Rose distinguishes between whites as the true "Southern people" and the "negroes" as something else. The prime lesson of the Klan, she wrote, was "the inevitability of Anglo-Saxon Supremacy."

Discussing the post-war period, Rose continued, "the sturdy white men of the South, against all odds, maintained white supremacy and secured Caucasian civilization, when its very foundations were threatened within and without."

The national UDC recommended that Rose's book be included in public school curricula and pressured school boards on the state and local level to require it in history classes.

The unanimous endorsement of Rose's book by all the state divisions of the UDC and the national organization itself undercuts any notion that white-supremacist sentiments were isolated to select state divisions like North Carolina's. In the late 1800s and well into the 1900s, the UDC as a whole advocated for white supremacy — so much so that they would raise a memorial to the Klan on equal terms to that of Confederate soldiers.

But in the UDC's eyes, a monument to the Klan and to the Confederacy were not merely equal: They were one and the same. After all, the UDC included the Concord Klan memorial in its own compilation of North Carolina's Confederate monuments and memorials. The conclusion is obvious — though not to a substantial number of Americans, particularly in the South.

The UDC of today is different than that of the Jim Crow era. Its members are committed to preservation of Southern and Union history, both black and white. They still raise funds for civic and charitable causes. They accept blacks as members. They have deeply held convictions and views regarding the Civil War, its causes, and the South in general. They zealously defend their monuments as honoring history and heritage and not racism, while making no apologies for the actions of their ancestors. Whether or not you agree with their views on history or monuments, their dedication to their communities is undeniable. It is an organization of complex, fascinating contradictions, some of its aspects wonderful and new, and some ugly and old — much like the South itself.

The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that there are more than 1,700 Confederate monuments and symbols still in public spaces around the country. They include named public buildings (including schools), highways, and the like. The count does not include monuments on private land, of which there are many. Not all of these are UDC monuments.

After the rioting in Charlottesville in 2017, the UDC issued statements rejecting racism and white supremacist groups. But it added this qualifier:;

We are saddened that some people find anything connected with the Confederacy to be offensive. Our Confederate ancestors were and are Americans. We as an Organization do not sit in judgment of them nor do we impose the standards of the 21st century on these Americans of the 19th century.

One would wonder if the UDC took into account its own memorial to the Ku Klux Klan.

But there's a problem with the notion that you can't judge the past with modern day morality: It means that, even today, the UDC is excusing and justifying slavery. It also means that the UDC is excusing and justifying the past actions of the Klan. And they are asking us all to do so.

Their qualifier also ignores the historical reality that American slavery was controversial even in its day. Half of the country considered it an abomination, as did almost all westernized countries that had already abolished slavery. The U.S. South was the exception.

This is who planted the forest.

* * *

Traipsing through the woods of Cabarrus County, North Carolina, in the June heat is not something I would recommend. After spending most of the day along Old Charlotte Road in Concord looking at every boulder I came across, that is where I found myself, plunging through underbrush, vines and briars.

Mrs. S.L. Smith's description of the location of the Klan memorial was somewhat vague: a bronze plaque placed on a natural boulder 12 feet high and 15 feet wide, beside Highway 15 four miles from Concord.

The Concord Ring Dike is the geologic term for the massive boulders that protrude from the ground in the area. Composed of syenite and gabbro rock, the formation is an oddity unique to that part of the state. Visually it's quite striking. Over the years, various groups have placed memorial plaques on the boulders. A good many still exist.

The landscape has changed drastically since 1926. Charlotte has expanded to the south side of Concord. Residential development has boomed, and what was once the two-lane rural road of Highway 15 is now remnants of Old Charlotte Road and the newer Highway 49, a four-lane highway with a grass median separating northbound and southbound lanes. A lot of earth was moved when 49 came through.

There were plenty of boulders to check, in front yards, at churches, at the old Stonewall Jackson Training School, which was created as a reformatory for white boys in the early 1900s as part of prison reforms championed by women's groups including the UDC.

After hours of driving and walking up along the road, knocking on doors, pestering a couple of Concord police officers at a nearby substation, and then checking the map again, I found myself on top of a hill just behind the tree line. There were several boulders of the right size, some covered in years of growth. Could this be where the Klan monument had been?

Then I found a curious thing. Just inside the tree line near some rocks was a 5-foot cross made out of heavy white PVC pipe, driven deep into the ground. Beer cans and liquor bottles littered the area. A roadside tribute to an accident victim, or something else?

The local historical groups were gracious and helpful but had no solid information about the monument's whereabouts either.

Picking my way back through the trees, I came to the clearing where I had entered the woods and walked down to the road to my car. I set out for home across the rolling green hills of Cabarrus County, where it seemed like every other house flew a Confederate flag. At one point, a quartet of Harley riders rumbled in front of me, the Confederate battle flag adorning their leather vests.

The scene brought to mind the words of one of the UDC's favorite monument inscriptions, which was taken from a short verse British poet Phillip Stanhope Worsley dedicated to Confederate General Robert E. Lee: "No nation rose so white and fair, or fell so pure of crimes."

* Correction: This story originally said that the UDC was founded by wives of Confederate veterans. While some of the older members may have been married to veterans, the founders were younger women married to men of influence who may not have been veterans themselves.

** Correction: This story originally said 200,000 due to an error introduced during editing.

Tags

Greg Huffman

Greg is a North Carolina attorney who also serves as the chancellor of the Western North Carolina Conference of the United Methodist Church.