Kavanaugh's role in championing a segregationist judge

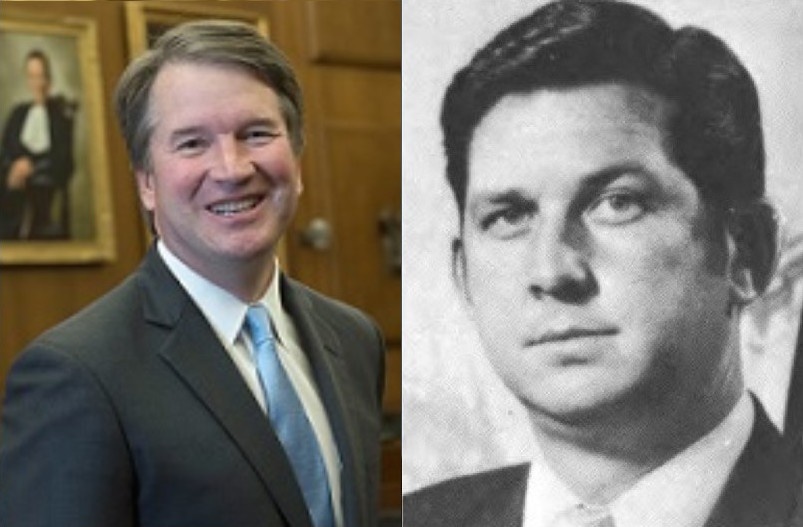

As a lawyer for the George W. Bush administration, Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh (left) worked on the push to confirm Charles Pickering (right) of Mississippi to a federal appeals court despite objections about the nominee's anti-civil rights record. (Kavanaugh photo from the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals; Pickering photo from the Mississippi official register.)

When U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh worked as an attorney for President George W. Bush, he helped to get Charles Pickering of Mississippi on the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals — despite questions about whether the attorney and former prosecutor left the Democratic Party because it embraced civil rights in the 1960s. Kavanaugh downplayed his role in the Pickering nomination at his first confirmation hearing in 2006, but recently released emails raise questions about whether in doing so Kavanaugh misled the Senate.

During his 2002 confirmation hearing, Pickering refused to answer a senator's questions about his decision to leave the party after the 1964 Democratic convention. Pickering told a local paper at the time that Mississippians were "heaped with humiliation and embarrassment" after black delegates, whom the state Democratic Party refused to seat, formed the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and demanded to be included.

The Democratic-controlled Senate rejected Pickering's initial nomination, but Bush renominated him after Republicans took control in 2002. New evidence then emerged that countered Pickering's claim that he had worked to improve race relations. Records unearthed by a reporter at Salon showed that Pickering had actually "worked to support segregation, attack civil rights advocates who sought to end Jim Crow, and back those who opposed national civil rights legislation."

Once in the Bush White House, Kavanaugh worked diligently behind the scenes to push Pickering's confirmation. He circulated information on the nominee to senators, and he worked on a lengthy op-ed by the attorney general supporting Pickering. But the Senate ultimately refused to confirm his nomination, leading President Bush to put him on the appeals court via a temporary recess appointment.

A few years later at his own confirmation hearing, Kavanaugh testified that Pickering was "not one of the judicial nominees that I was primarily handling." However, the new emails show that on Jan. 28, 2003, he had a list of six "to-do" items related to the Pickering confirmation.

Earlier this month, U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California said that Kavanaugh "led on key parts of the Charles Pickering nomination, which he denied." Feinstein and other Democrats are protesting that only a fraction of Kavanaugh's papers will be available by the time of his Supreme Court confirmation hearing on Sept. 4. So far Republican leaders have refused to slow the process.

Segregation's ghosts

When Pickering was nominated in 2002, Mississippi was wrestling with the political ghosts of its segregationist past. That year, for example, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott of Mississippi was forced to resign after praising Sen. Strom Thurmond's 1948 segregationist presidential campaign. During a celebration of Thurmond's 100th birthday, Lott said Mississippi was proud to have supported the campaign.

"And if the rest of the country had followed our lead," he added, "we wouldn't have had all these problems over all these years, either." Lott was Pickering's strongest supporter in the Senate, and media accounts speculated that the nomination was doomed after Lott stepped down.

Pickering was an eyewitness to history as part of the pro-segregation Mississippi Democratic Party's all-white delegation to the 1964 Democratic convention. Fannie Lou Hamer and other black civil rights activists formed the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) as a rebuke to segregationists and demanded to be seated. After the MFDP delegates were given formal at-large status, Pickering and his fellow white delegates walked out. That's when he told a reporter that the MFDP had embarrassed Mississippi.

After Pickering's renomination, records from his longtime law partner, the staunch segregationist Carroll Gartin, showed that Pickering had switched to the Republican Party due to the Democrats' evolving support for civil rights.

At Pickering's confirmation hearing, senators also asked him about his contacts with Mississippi's notorious Sovereignty Commission, a taxpayer-funded, segregationist agency that targeted civil rights activists and sympathizers. Pickering claimed he contacted the commission because the Ku Klux Klan had infiltrated a local labor union, but the commission's records showed that he had actually contacted it about a civil rights group infiltrating the union.

National civil rights groups came out hard against Pickering. Julian Bond, at the time the NAACP's national chair, told senators that "a vote for Pickering is a vote against civil rights."

However, some Mississippi civil rights leaders initially supported the nominee. The newly released emails show Kavanaugh sent his colleagues news items featuring local black leaders backing Pickering. Charles Evers, the brother of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers, praised Pickering's role in the prosecution of several members of the Ku Klux Klan. Said Evers:

Judge Pickering was a locally elected prosecutor who took the stand that year and testified in the criminal trial against the Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, who was accused of firebombing a civil rights activist. Judge Pickering later lost his bid for reelection because he dared to defy the Klan.

Pickering's supporters also cited the fact that he sent his children to integrated public schools at a time when many wealthy white Mississippians did not. Evers continued to defend Pickering even after his law partner's papers and the Sovereignty Commission's records surfaced.

Unprecedented opposition

Kavanaugh is expected to face questions at his Supreme Court confirmation hearing about whether he previously misled senators about his role in the Pickering nomination and other controversial Bush administration actions such as the torture of terror suspects. Civil rights advocates and other progressive groups are protesting the nominee, who has the least public support of any Supreme Court nominee in decades. When he was nominated to his current position on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in 2003, he was not confirmed until three years later amid concerns about his record.

Critics worry that Kavanaugh would vote reliably with the other conservatives to reject challenges to voter suppression laws. In 2012, for instance, Kavanaugh wrote an opinion rejecting a challenge to South Carolina's voter ID law. The U.S. Department of Justice had blocked the law under the Voting Rights Act because it would have disproportionately impacted black voters, marking the first time since 1994 that the Department blocked a voter ID law. South Carolina appealed to the D.C. Circuit, which allowed the law to go into effect. Kavanaugh's opinion said the law was not discriminatory and noted that in recent years "many states … have enacted stronger voter ID laws."

A recent report from the Lawyers' Committee for Civil and Human Rights raises concerns that Kavanaugh adheres to the idea of a "color-blind Constitution" that, for example, does not conform to Supreme Court precedents allowing universities to use affirmative action policies to achieve diversity. The progressive think tank Demos agreed and explained that the "color-blind" approach "is a way of pretending that discrimination does not exist, or that it would disappear if we would just not focus on it."

Kavanaugh's Supreme Court nomination comes amid a record number of confirmations of President Trump's judicial nominees, 90 percent of whom are white. And it is happening while Trump faces allegations of criminal activity and possible impeachment. Even though he worked for Kenneth Starr's investigation of President Bill Clinton, Kavanaugh changed his mind about investigating the president after Clinton left office and he went to work for President George W. Bush. He has since said that the law authorizing special prosecutors like Starr is unconstitutional and that a sitting president cannot face criminal charges.

Despite the many concerns about Kavanaugh's record, Republican leaders in the Senate are moving at a brisk clip, with the goal of confirming Kavanaugh before the November election.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.