What's next for ex-felon voting rights

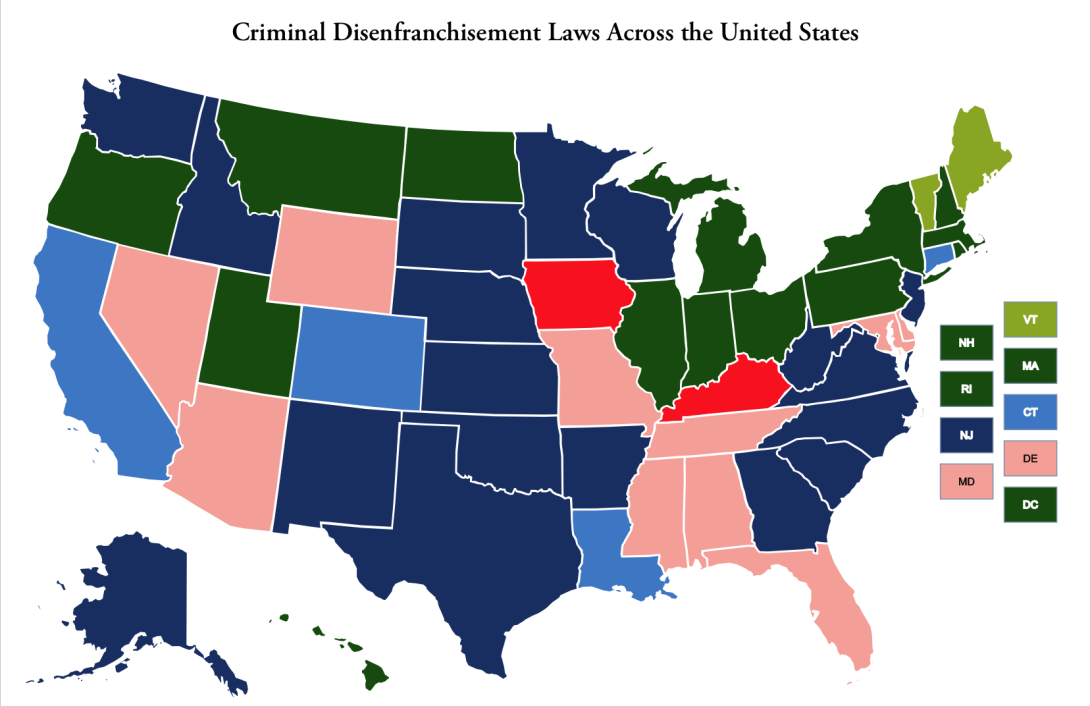

This map from the Brennan Center for Justice shows criminal disenfranchisement laws by state. Kentucky and Iowa, in red, are now the only states to permanently disenfranchise people with felony convictions. Those in pink permanently disenfranchise at least some people with felony convictions; dark blue states restore voting rights upon completion of prison, parole, and probation; those in lighter blue allow people on probation to vote; dark green states automatically restore voting rights after release from prison; and those in lighter green do not disenfranchise people with criminal convictions. To view the original map with more details, click here.

A new state constitutional amendment took effect in Florida this week that automatically restores voting rights to most ex-felons in the state, except for those convicted of murder or sexual offenses. The state's voters approved Amendment 4 in November by a margin of 64.5 percent, more than the 60 percent needed to pass.

The new policy makes up to 1.4 million Floridians eligible to register to vote again, a group that's disproportionately black. Many of these returning citizens showed up at local elections offices on Jan. 8, the day the new policy was implemented, to register in person.

Among them was Desmond Meade of Orlando, president of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC), a broad, nonpartisan effort that brought together groups ranging from the ACLU to the Christian Coalition for the Amendment 4 campaign. He lost his voting rights after being convicted of a drug- and firearms-related offense in the early 2000s, and later went on to earn a law degree from Florida International University.

Meade was accompanied at the voter registration office by his wife, Sheena, and three of their five children. He described the moment as "just overwhelming." Other new returning-citizen registrants told reporters that they felt like "a part of this society" and like "a human being again." FRRC political director Neil Volz, who lost his voting rights over a conviction for his role in the Jack Abramoff public corruption scandal and who now works with a homeless services and addiction ministry program in Southwest Florida, called Jan. 8 a day of celebration for him and other returning citizens.

In a call with amendment supporters the day before the policy took effect, Meade and Volz discussed the next step organizers are planning: actually getting people registered. But the campaign will do more than simply register them. It will also emphasize education and engagement to ensure new registrants actually show up to cast ballots.

"We want to make civic engagement and voting something that is fun again," said Meade.

Organizers say they don't want to limit outreach to returning citizens but will target all eligible Floridians who haven't registered to vote. There are 4.6 million Florida residents who can drive but aren't registered, according to the Electronic Registration Information Center, a national nonpartisan group that works to improve the accuracy of state voter rolls. However, that number includes non-citizens and others ineligible to take part in elections; in addition, there are some felony convictions that affect an individual's ability to get a driver's license in Florida.

FRRC organizers are now hatching a voter engagement plan with help from voting rights groups including the League of Women Voters and the NAACP. They're also working with voting rights attorneys from nonprofits including the ACLU, Advancement Project, Brennan Center for Justice, and Demos, as well as private-practice attorneys, to address any problems that may arise with the new policy.

Though Amendment 4 was crafted to be self-implementing, Florida's newly sworn-in governor, Ron DeSantis (R), has repeatedly tried to cast doubt on that by calling for implementing legislation to spell out the rights restoration process. The legislature convenes on March 5.

But legal experts, including the head of the state ACLU and the Republican state House speaker, say the amendment's Jan. 8 effective date is clear.

A legal challenge in Kentucky

Previously, Floridians who had completed felony sentences had to seek restoration of their voting rights through an arduous individual process before the state's Executive Clemency Board. With implementation of Amendment 4, restoration will happen automatically for those covered.

Now, the only two states that impose lifetime bans on voting for people with felony convictions are Iowa and Kentucky. While the Virginia constitution also permanently disenfranchises citizens with past felony convictions, it gives the governor authority to restore voting rights. After the Virginia Supreme Court struck down former Gov. Terry McAuliffe's (D) 2016 executive order automatically restoring voting rights to over 200,000 citizens, he began individually restoring rights to qualified people who completed their sentences, a policy that's been continued by current Gov. Ralph Northam (D).

These harsh felon disenfranchisement policies, which have roots in the Jim Crow era, have the effect of disproportionately suppressing the black vote. In Kentucky, for example, nearly one in 10 of the state's adults have lost their right to vote because of a felony conviction. But the figure for African American Kentuckians is one in four — the highest rate of black disenfranchisement in the nation.

Kentucky's policy is facing a legal challenge, however.

This week, the day after Florida's Amendment 4 took effect, Fair Elections Center and the Kentucky Equal Justice Center sent out a press release announcing that they had joined a lawsuit challenging Kentucky's felon disenfranchisement policy. The action was brought on behalf of four Kentuckians with felony convictions: Stephon Doné Harbin, Bryan LaMar Comer, Roger Wayne Fox II, and Deric James Lostutter.

Currently in Kentucky, those who have completed felony sentences and want to vote again must apply to the Department of Corrections' Division of Probation and Parole, which screens applications. It then forwards them to the governor, who has the power to grant or deny restoration. But there are no specific rules governing those determinations. The lawsuit says the arbitrariness of the process and risk of biased treatment violates the U.S. Constitution:

An unbroken, 80-year-old, and well-settled line of Supreme Court precedent prohibits the arbitrary licensing of First Amendment-protected conduct. This is because the risk of viewpoint discrimination is highest when a government official's discretion to authorize or prohibit First Amendment-protected activity is entirely unconstrained by law. Officials with unfettered authority to selectively permit felons to vote may grant or deny restoration applications on pretextual grounds while secretly basing their decision on information or speculation as to the applicant's political affiliation or views, the applicant's race, faith, wealth, or other characteristics. This is why conditioning the enjoyment of a fundamental constitutional right on the exercise of unfettered official discretion and arbitrary decision-making violates the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

"With Florida adopting a non-arbitrary voting rights restoration system, Kentucky is fighting an increasingly lonely battle to preserve a 19th century system that forces American citizens to plead for restoration of their voting rights," said Jon Sherman, senior counsel at Fair Elections Center. "This lawsuit gives state officials and legislators an opportunity to reform a broken and unconstitutional system which excludes hundreds of thousands of people from our democracy, even if they have already done everything the criminal justice system required of them."

The lawsuit is asking the court to order Kentucky to create a non-arbitrary system for rights restoration, with specific and neutral criteria for all residents with felony convictions.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.