Gov. Abbott's long record of voter suppression

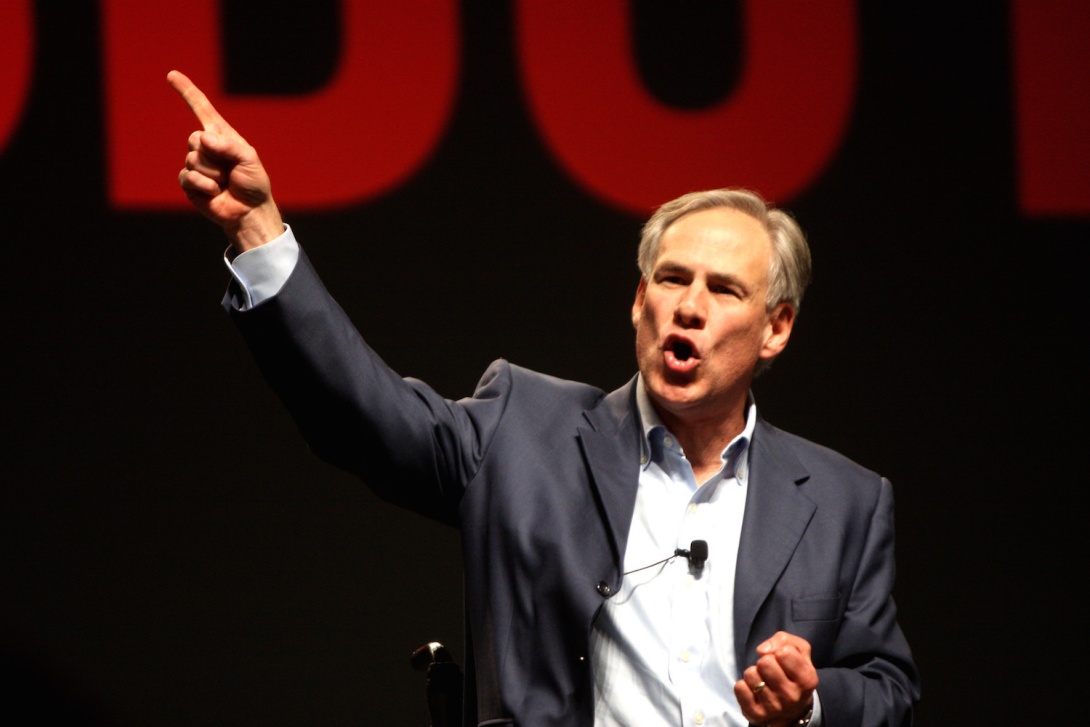

Voting rights advocates say Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) has done more to undermine voting rights for African Americans and Latinos than any other modern-day governor. (Photo by Gage Skidmore via Flickr.)

Texas Secretary of State David Whitley resigned last month after his reappointment bid lost the support of state lawmakers because of his failed effort to remove from the state's voter rolls more than 90,000 people he wrongly claimed were not citizens. The voter purge was blocked by a federal court after a lawsuit brought by the state and national chapters of the League of United Latin American Citizens.

According to recently released electronic correspondence, Whitley was acting under the direction of Gov. Greg Abbott, a fellow Republican. The emails show that Abbott pushed for the voter information used to initiate the purge, though Abbott's office has denied that he gave the instruction to launch the process.

This wouldn't be the first time Abbott has been involved in voter suppression: Since his time as Texas attorney general, Abbott has repeatedly supported restrictive voting policies designed to curb the political influence of a diverse electorate. Maintaining without evidence that voter fraud is rampant in Texas, he has been part of various schemes that directly impact the power of voters of color.

Abbott "has done more to damage and undermine African-American and Latino civil and voter rights" than any modern-day governor, according to the Arlington, Texas, branch of the NAACP.

As attorney general from 2002 to 2015, Abbott was a staunch supporter of voter ID requirements that have been shown to discriminate against people of color — a fact he vehemently denied. "There is absolutely zero proof, zero proof, that there is any suppression of the vote whatsoever because of voter ID laws," Abbott said in 2014 before the November election in which he would become governor.

Originally introduced in 2011, Texas's voter ID law was considered to be one of the nation's strictest and could have excluded up to 600,000 voters. The measure limited acceptable forms of identification and made no exceptions for reasonable impediments to getting one. The law was blocked by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2012 under the Voting Rights Act (VRA).

But after the Supreme Court struck down a key part of the VRA, Texas officials rushed to implement the voter ID requirements — a decision Abbott celebrated. "With today's decision, the state's voter ID law will take effect immediately," he said at the time. "Photo identification will now be required when voting in elections in Texas."

In response, the DOJ and voting rights groups filed a federal lawsuit against the state, arguing that the voter ID law discriminates against minorities and suppresses voter turnout. With Attorney General Abbott at the helm, Texas continued to defend the law in court. In April of this year, a federal appeals court upheld the law, which the legislature revised to allow people who lack an authorized photo ID to show other documentation, such as a utility bill. The court said the revisions had made "improvements for disadvantaged minority voters."

No escape from liability

Along with the voter ID bill, Abbott also endorsed a controversial redistricting proposal that opponents argued was racially biased.

Between 2000 and 2010, Latinos and African Americans accounted for 90 percent of Texas' population growth, resulting in the state becoming majority minority. In response to the changing demographics, the Republican-controlled state legislature redrew congressional and legislative maps in a way that undermined the political influence of non-white voters.

As attorney general, Abbott denied that the maps were motivated by race, though he acknowledged that the districts were designed to benefit Republican candidates. "In 2011, both houses of the Texas Legislature were controlled by large Republican majorities, and their redistricting decisions were designed to increase the Republican Party's electoral prospects at the expense of the Democrats," as Abbott wrote in a court brief at the time.

Civil rights groups and voters of color immediately challenged the proposal in federal court. They argued that, because of the surge in the Latino population, 13 or 14 districts should have been allocated to the state's Hispanic population, which instead was packed into nine. The federal court produced a temporary redistricting plan that was used in the 2012 elections while the new maps were pending DOJ preclearance. Texas subsequently adopted the court's interim maps on a permanent basis in 2013, but the plaintiffs continue to argue that those maps still had a discriminatory effect against minority voters.

In 2017, the federal court concluded that state lawmakers "intentionally diluted the Latino vote," which violates the Voting Rights Act and the 14th Amendment. The state appealed to the Supreme Court, where last June the justices in a 5-4 decision upheld Texas's legislative and congressional maps.

In response to the Supreme Court's ruling, Abbott tweeted: "Contrary to Democrats repeated claims to contrary the Supreme Court rules Texas lawmakers did not intentionally discriminate in drawing political maps. Our legislative maps are legal." The decision concluded a legal battle that continued for much of a decade and will impact the future of elections in the state for years to come.

"Greg Abbott as attorney general was the mastermind of both a failed redistricting plan that has intentionally discriminated against minority voters, and he was also the chief architect of clearing a voter ID proposal that was also found to be discriminatory," said state Rep. Trey Martinez Fischer, a San Antonio Democrat who served as a plaintiff in lawsuits against both the voter ID measure and the redistricting proposal. "The fact that he's governor now doesn't give him an escape from liability or responsibility for setting that tone."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.