What's at stake for Southern Dreamers awaiting a SCOTUS decision on DACA

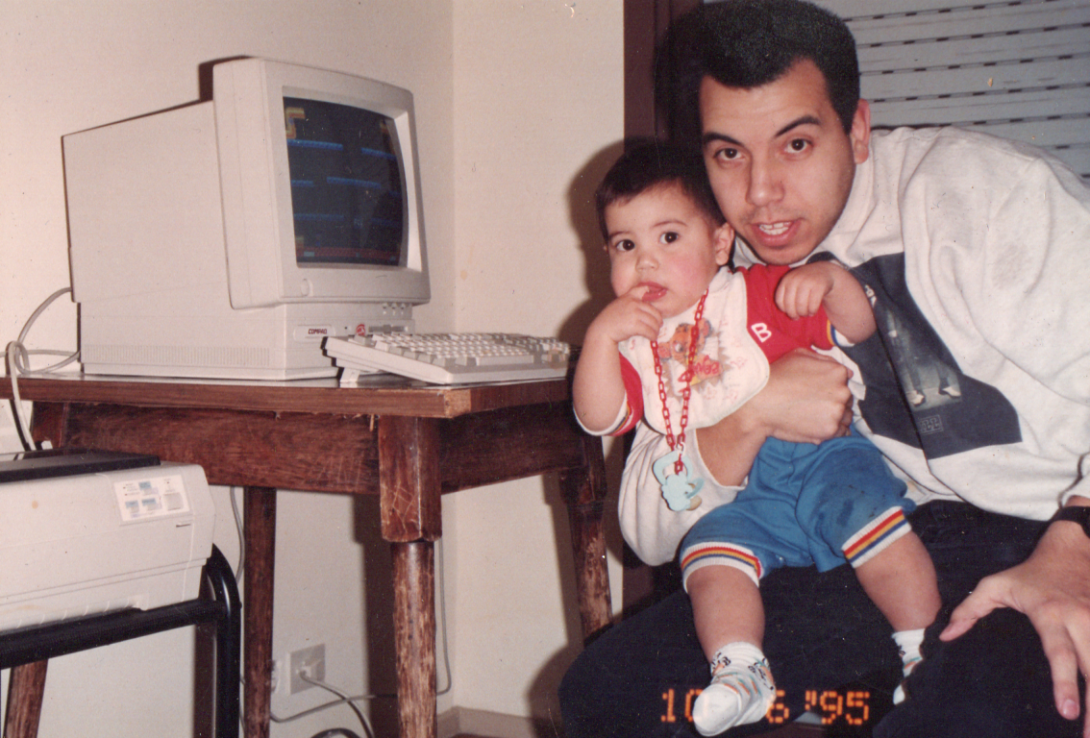

Tomás Monzón with his father in Buenos Aires, Argentina. (Photo courtesy of Tomás Monzón.)

The South is home to one-third of all Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, undocumented immigrants who arrived in the U.S. as children and whose deportations have been temporarily waived by an Obama-era program.

Tomás Monzón is one of them.

In June 2012, Monzón, then a recent high school graduate and valedictorian, was months shy of a one-way trip to Buenos Aires, Argentina, a place he last set foot in at age 6. He says he didn't want to continue living in the U.S. as an undocumented immigrant.

But then DACA was announced.

"My immediate thought was 'yeah that kind of sounds like what I need but there must be some catch,'" he said. "It took me a few days to really wrap my head around it. It was really a blessing."

Monzón remained in the country. He applied to the Obama-era program and received a work permit. Now 25, he's built more than a quarter of his life under DACA. He's travelled to Boston, San Antonio and Puerto Rico. He owns a car and has a driver's license. He is not afraid of being deported.

In seven years, DACA has changed what Monzón can access. But it has not solved his problem: Though DACA lets him work legally, he has no lawful status.

In that immigrant twilight zone, Monzón has built a life.

Déjà vu?

On Sept. 5, 2017, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions made his way to a podium at the Department of Justice. He straightened out a stack of papers, greeted those present, and within several seconds announced DACA's end, throwing the plans of more than half a million beneficiaries into question.

"This will … create a time period for Congress to act — should it so choose," Sessions said of the program.

DACA had come full circle. Only five years earlier, in 2012, then-President Barack Obama had rolled out the program as a Band-Aid solution meant to force Congress' hand.

"Precisely because this is temporary," Obama said then, "Congress needs to act."

But Congress has passed no legislation addressing the status of DACA recipients. And its failure to act has left active beneficiaries clinging to the words of two administrations that agreed on at least one point: The program is temporary.

DACA advocates challenged the Trump administration's decision to end the program in lower courts. And their efforts kept it partially alive.

That legal process came to its final stages last month, when a collection of DACA-related cases was heard before the U.S. Supreme Court. Those arguments will now decide the fate of the program.

Meanwhile, since receiving DACA, Monzón has graduated college and landed several jobs.

Figuring out you're undocumented

Monzón's family settled in South Florida in 2001. He says his father left a telecommunications company in Argentina and picked up food service jobs around Miami. His father made ends meet as he could.

"He would sometimes take me to school on the back of a bicycle," Monzón says.

But Monzón was unaware of his family's legal status until he asked his mother about an amusement park discount on the back of a soda can.

They are meant for Florida residents only, he remembers her saying.

"What do you mean Florida residents?" he asked. "We live in Florida. Why can't we qualify?"

Only much later did his mother's answer fully dawn on him.

'The egg has been scrambled'

DACA has let its recipients weave themselves deep into the American fabric.

Many beneficiaries have tapped into the U.S. credit system, and through their employers have accessed private health insurance plans and retirement accounts.

A recent survey of more than 1,100 DACA beneficiaries published by the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, shows 89 percent of respondents are currently employed. Nearly 80 percent say they've earned more money after receiving DACA, more than 65 percent say they've received their first credit card, and nearly 60 percent say they've bought their first car.

The potential loss of these benefits concerns not just DACA sympathizers.

In August 2018, after Texas and other states asked a federal judge to halt the program, Judge Andrew Hanen, presiding over the case, compared the idea of ending DACA to an unrealistic operation.

"Here, the egg has been scrambled," he wrote. "To try to put it back in the shell with only a preliminary injunction record, and perhaps at great risk to many, does not make sense nor serve the best interests of this country."

A South without DACA

Living in Florida, Monzón stands to lose more if the Supreme Court were to let the program end than if he lived in an immigrant-friendly state like California.

He would lose not only his work benefits. Since Florida and other Southern states do not give undocumented immigrants driving privileges, he'd be unable to legally drive.

"Once your driver's license expires … then that cuts off your ability to go to work, to go to the hospital, to go to school, to do anything in your life," says Bruna Sollod, communications director at United We Dream, a national advocacy group for immigrant youth.

For Monzón, losing the ability to drive legally would be just the tip of the iceberg.

Florida is one of several states where local jurisdictions have voluntary agreements with the federal government allowing their officers to take on limited immigration enforcement functions.

A Florida law that recently came into effect goes even further by requiring police officers to help ICE, the Department of Homeland Security's immigration enforcement agency. Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) argues the law will make communities safer.

And this could soon be Monzón's new reality if the U.S. Supreme Court were to let DACA end.

But he remains optimistic.

"I always try to do things in such a way that if the current reality does a 180, I'm ready to tackle what happens," Monzón says. "If tomorrow I did have to leave to Argentina, I'd like to think I'd be able to do it."

Tags

Rolando Zenteno

Rolando Zenteno is the inaugural recipient of the Julian Bond Fellowship with Facing South.