Ranked-choice voting could fix the problem of ballots cast for dropouts

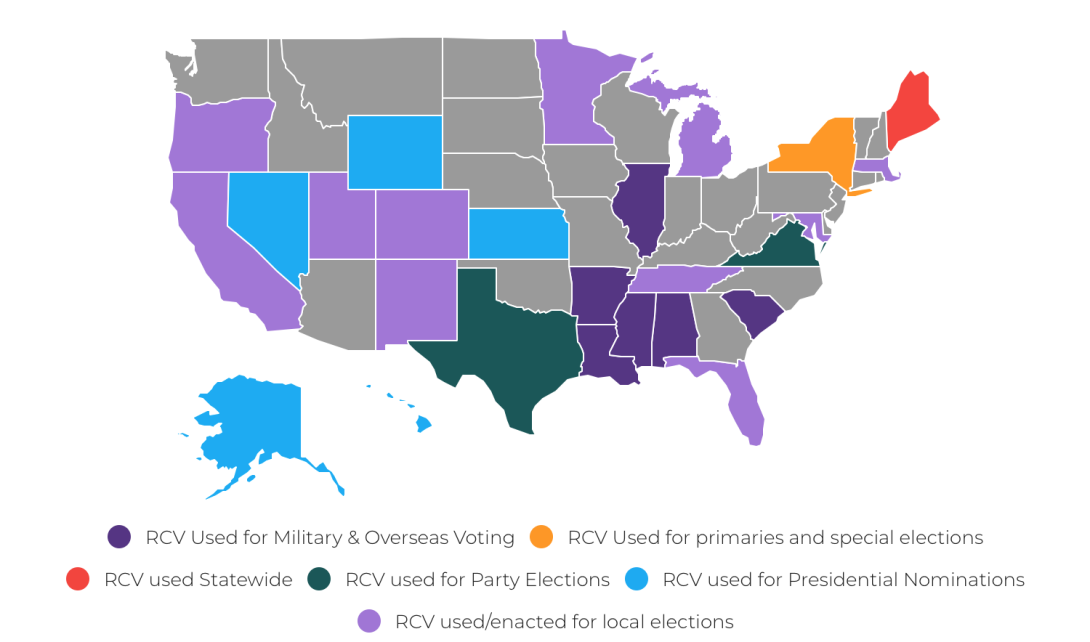

Over the last two decades, a growing number of states and localities have adopted some form of ranked-choice voting. The decision by some Democratic presidential candidates to drop out of the race after early voters already cast ballots for them has renewed interest in the system. (Map via FairVote.)

Thirty-eight states nationwide, including eight in the South, have early voting, which allows voters to cast ballots up to two weeks before the official Election Day. Democracy advocates embrace early voting because it gives voters flexibility and cuts down on some of the challenges they can encounter on Election Day, like long lines and precinct confusion. And in some states, it also gives voters the ability to register on the same day they cast their ballots and vote at polling places outside of their assigned precinct.

But right before March 3's Super Tuesday, when voters in 14 states headed to the polls, three Democratic presidential candidates — Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, and Tom Steyer — dropped out of the race. In California alone, over over 2.5 million people cast early ballots, and polls found that somewhere between 1/8 and 1/5 of early voters in Super Tuesday states had voted for Buttigieg and Klobuchar.

With many early voters lamenting that they had wasted their votes, political observers pointed to a potential solution: ranked-choice voting (RCV), also known as preferential voting or instant-runoff voting.

Under this system, which is currently used to elect the presidents of India and Ireland, voters would rank all candidates in the race by order of preference. If a candidate wins a majority of voters' initial choices, then they are declared the winner. If no candidate wins the majority outright, the person with the least number of first-preference votes is eliminated, their votes are distributed to the second-choice candidates, and a new tally is conducted. This process continues until there is a clear majority winner. Since U.S. presidential primary candidates need to win at least 15% of the votes to receive delegates, the candidate with the least number of votes below that threshold would be eliminated first.

Supporters of RCV believe it has the potential to minimize wasted votes and better reflect the voters' will.

"Ranked-choice voting makes democracy more fair and functional," according to FairVote, the Maryland-based nonprofit that advocates for electoral reforms including RCV. "It is a form of fair representation voting which more accurately represents the full spectrum of voters".

RCV's long history

Besides determining the results in single-winner elections like a presidential primary contest, RCV can also determine the results in multi-winner elections, like city councils. While a candidate in a single-winner election must receive at least 50% of the vote to win, candidates in an election for three council seats, for example, must receive at least 25% of the vote.

Ashtabula, Ohio, became the first place in the United States to use multi-winner RCV in its 1915 city council election. From there, cities across Ohio and elsewhere began to use RCV, with New York City embracing the multi-winner form to decide its school board elections in 1936.

By the early 1940s, nearly two dozen cities in six states — none in the South — were using some form of RCV, but a repeal effort soon followed. During the 1940s and '50s, the system was repealed in 23 of the 24 cities where it was being used; by 1962, Cambridge, Massachusetts, was the only city with its RCV system still in place.

There's been an RCV resurgence in the U.S. over the past two decades. Maine is currently the only state to use RCV for statewide and federal races. But nationwide, more than 20 cities have adopted RCV, though some have not yet implemented it, including New York City. Voters in Sarasota, Florida, and Memphis, Tennessee, approved local RCV in 2007 and 2008, respectively, though county and state officials have effectively blocked its implementation. Elsewhere in the South, RCV is also currently used for military and overseas voting for congressional runoffs in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, and for state Democratic Party elections in Texas and Virginia.

Meanwhile, there have been over a dozen bills proposed in Southern states in recent years including North Carolina and Virginia to implement RCV, though few have passed. In North Carolina, for example, a bill to establish RCV for any state or federal office, with the exception of the presidency, was sent to the House Elections Committee in April 2019. But earlier this year in Virginia, the legislature approved two measures to allow municipalities in the state to adopt RCV in certain local elections. The bills are now awaiting Gov. Ralph Northam's (D) signature.

Though support for RCV is growing, it is not without its problems. The system is more complicated than single-choice voting, and fatigued voters could be less likely to rank the entire ballot, skewing the election results. And when there was an RCV referendum on the ballot in New York City last year, which ultimately passed, the city council's Black, Latino, and Asian Caucus spoke out against it over concerns that it could hurt candidates of color by requiring them to get a majority of votes to win.

A study by FairVote in California's Bay Area found that candidates of color won 62 percent of ranked-choice races, compared to 38 percent before the switch. But Craig Burnett, an associate professor of political science at Hofstra University, found that voters in black and Latino neighborhoods there were more likely to choose just one candidate and leave the rest of the ballot blank, while voters in white neighborhoods were more likely to complete the ballot, increasing their influence.

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.