Experts warn that the 'sky is falling' for rural health care in the South

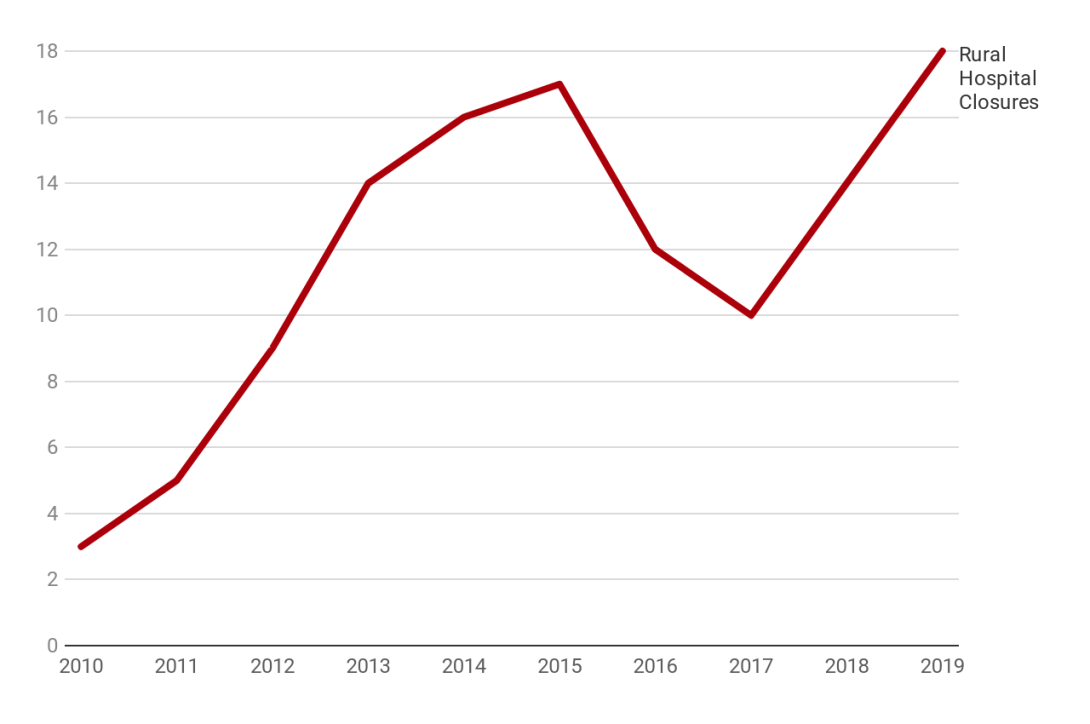

As of May 12, more than 43,000 people living in the rural South have been infected with the coronavirus. Over 1,700 have died. The outbreak, compounded by the financial strain the fallout from COVID-19 has wrought on health care providers across the country, has many experts worried that the pandemic could hasten the closure of rural hospitals providing critical care to underserved populations.

"I don't tend to be a doom and gloom person," said Michael Topchik, the national leader for the Chartis Center for Rural Health, a research and consulting group. "But I think right now, the sky is actually falling."

Nearly 200 rural hospitals across the South are in counties that have already seen at least one death from COVID-19 and have budgets in the red, according to a Facing South analysis of data reported to the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2017. The South's rural hospitals have struggled in the past several years, due in part to federal policy changes that affect how rural hospitals are paid by safety net programs, and to the continued refusal of most Southern states to expand Medicaid.

"They may be having an influx of patients. That doesn't mean they're having an influx of money," said Max Isaacoff, the government affairs and policy manager at the National Rural Health Association, an advocacy group for providers.

A February report from the Chartis Center, co-authored by Topchik, which analyzed past rural hospital closures to understand what could lead to future closures, found that 241 rural hospitals in the South were vulnerable to closure. Of those, 77 are in Texas, 27 in Mississippi, and 25 in Tennessee. Many of the backstops in place in other regions of the country — a high number of hospitals operated by state governments, for instance, or the expansion of Medicaid — are far less prevalent in the South. In every Southern state except Florida, more than 40 percent of rural hospitals operate with negative margins. And in Tennessee and Texas, two states which have not expanded Medicaid, the Chartis Center found that more than 50 percent of rural hospitals were vulnerable to closure.

That was all before the pandemic. COVID-19 has led most Southern states to ban elective procedures, and made patients fearful of coming into hospitals and clinics for regular check-ups. For many rural health providers, outpatient procedures traditionally fill the gaps left by treating uninsured patients, providing about 75 percent of total revenue — and losing them has been a near-death blow.

Negative margins alone won't necessarily force a hospital to close, but lack of financial flexibility does make it hard to pay staff, keep pace with changing technology, and, during a pandemic, purchase personal protective equipment as costs rise. Rural hospitals in the South are more likely to serve poorer communities, which makes them more reliant on public health insurance programs like Medicare and Medicaid to keep their doors open. But in states that have not expanded Medicaid, hospitals are treating more uninsured patients and not being compensated for their care.

"We support Medicaid expansion," said Isaacoff. "It's just in the data. Expansion states are doing better with their rural hospitals than non-expansion states."

Of the 740 Southern hospitals that reported a negative net income to the CMS in 2017, 13 in rural communities closed over the next two years. At least nine of those are in counties that have seen at least one COVID-19 death. And with revenues plummeting, the in-the-red rural hospitals that are not in counties with large COVID-19 outbreaks are still not protected from the disease or its fallout.

"I think what we are seeing is probably some long-term systemic damage to the safety net, and some patterns of behavior amongst consumers and patients that could have a long-lasting impact on the rural hospital safety net," Topchik said.

Rural health advocates have long argued that the federal government's policies around rural health care do not match the reality on the ground. "There has to be a new payment model," Isaacoff said. "Rural hospitals are not the same as urban hospitals."

Widening disparities

The threat to health care access presented by the closure of rural hospitals is not months or years away — it's already here. And it threatens some communities more than others.

Last month, the West Virginia Gazette-Mail reported that, in Fairmont, West Virginia, an African-American woman sick with COVID-19 symptoms had to take an ambulance ride of more than 25 minutes to a hospital emergency room in a different county. Just weeks earlier, that ambulance ride would have been to the Fairmont Regional Medical Center, in her own town, which closed near the end of March because of financial difficulties unrelated to the pandemic. As the COVID-19 outbreak continues to escalate, experts say they expect rural hospital closures to accelerate.

A 2015 report from the Sheps Center for Rural Health, which tracks rural hospital closures, found that from 2010 to 2014, hospitals were more likely to be "abandoned," meaning closed entirely, with no type of even outpatient care still provided, in markets with a higher proportion of black patients.

Rural African-American communities are at particular risk of losing health care — and have been particularly vulnerable to the coronavirus. According to a Facing South analysis of Census Bureau data and county-level COVID-19 data from USAFacts, four of the five rural Southern counties with the highest numbers of COVID-19 deaths have a population that is more than 45 percent black. In each of these counties, more than 25 people have died. Early County, Georgia, with a population of just over 10,000 people that is more than 50 percent black, had 228 cases and 27 deaths as of May 12. And each of the dozen rural Southern counties with the highest death rate from COVID-19 has a black population of more than 25 percent. The three counties with the highest COVID-19 deaths per capita are all more than 50 percent African-American.

In many parts of the Black Belt, coronavirus tests are still hard to come by. "Our health care system was not necessarily built to ensure that people of color, and black people in particular, thrive in the same ways that white communities do," said Dr. Rachel Hardeman, a professor at the University of Minnesota's School of Public Health whose research focuses on health disparities.

The disparities threaten to persist through the pandemic, and even after it ends. Many rural health care providers are transitioning to telemedicine to keep patients from having to come into a doctor's office, but rural African Americans are less likely to have access to broadband internet — making it harder for them to see a doctor or primary care physician while the pandemic stretches on. A 2019 study from the University of South Carolina's Rural and Minority Health Research Center found that rural African Americans are much more likely to live in counties with persistent poverty, and more likely to live in regions that the federal government has designated as Health Professional Shortage Areas.

Though there has been some federal funding allocated to rural hospitals during the pandemic, the experts Facing South spoke to said it was not enough to ensure long-term stability. Topchik characterized the measures as a "stopgap." Barring a more robust influx of funding, some hospitals may close entirely. But others will simply choose to cut certain types of services, and begin sending some patients to hospitals in more populous cities for specialized types of care.

One of the most frequent targets for cuts in rural regions is obstetrics wards, said Isaacoff of the National Center for Rural Health. This could be an especially hard loss for black women in the rural South; birth services are already less accessible to black women in the region, and many were already wary of rural health care providers due to a history of subpar treatment.

But if rural hospitals begin closing the doors on their maternity wards, Hardeman told Facing South, health care for black mothers and their children might only get worse. And that will have long-lasting effects.

"Who has access to care and who doesn't have care has implications for generations to come," she said. "It's one of the ways that social inequities continue to replicate themselves, and it continues to depress the ability for a community to thrive."

Tags

Olivia Paschal

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Virginia. She was a staff reporter with Facing South for two years and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South's year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also led the Institute's project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive.