Here's what's driving the rural South's COVID-19 outbreaks

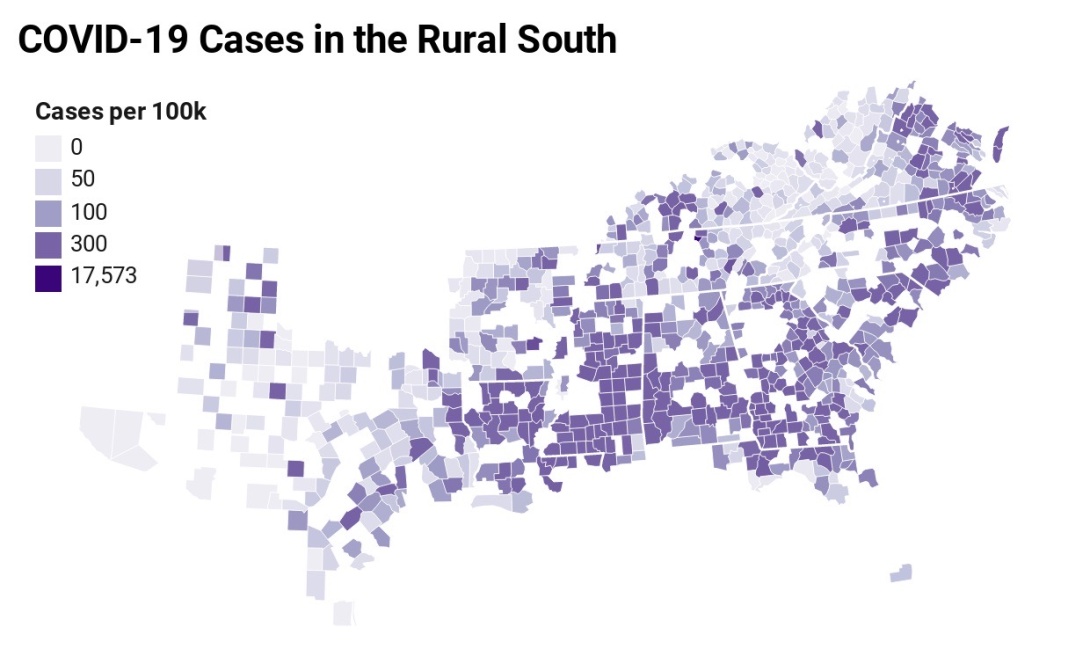

This map shows COVID-19 cases per 100,000 residents in rural Southern counties. (Interactive map by Olivia Paschal using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and USAFacts.org.)

A new Facing South analysis of county-level data across the rural South finds that COVID-19 has hit counties with prisons and meatpacking plants particularly hard, along with majority-black rural counties across the Deep South.

Four of the 10 worst current confirmed outbreaks in the U.S. are in rural Southern counties*, all of them driven by a significant prison outbreak. That includes the nation's most concentrated outbreak, in Trousdale County, Tennessee, where the confirmed case rate is 17,573 people per 100,000. The majority of the county's 1,383 confirmed cases are located in Trousdale Turner Correctional Center, a private prison run by Tennessee-based CoreCivic.

Confirmed case rates don't tell the whole story, though: In some places, including Tennessee, they may reflect where state governments have chosen to devote testing resources, rather than the actual extent of the outbreak, said Whitney Zahnd, a research assistant professor at the Rural and Minority Health Research Center at the University of South Carolina's Arnold School of Public Health. Still, she said, it is noteworthy that many of the most concentrated outbreaks in the South are in rural counties, driven in every case by prisons and meat processing plants that were often brought into communities as economic drivers.

Calculated in terms of cases per 100,000 people to standardize rates among places with disparate populations, the five worst outbreaks in the rural South are in counties with prisons. Each of these counties have more COVID-19 cases per 100,000 residents than New York City, the site of the largest U.S. outbreak in terms of overall numbers.

An outbreak at a prison is not confined within its walls: The virus may have come in through an employee or incarcerated person, and it may be spread out into the community by workers moving in and out of the prison, or by prisoners being sent to work elsewhere. In rural Lincoln County, Arkansas, an outbreak at the Cummins Unit state prison has driven the infection of 965 people, including at least 900 inmates and 60 staff members, and led to eight deaths. In Arkansas, prison guards are currently allowed to go to work while infected.

Meatpacking plants are also a factor behind the rural South's high COVID-19 case numbers. Marshall County, Alabama, is home to a Wayne Farms chicken processing plant and has the fourth-most total cases of any rural Southern county. Virginia's Accomack County is the site of another recent outbreak related to meatpacking; infections at Tyson and Perdue poultry plants there have contributed significantly to its 688 positive cases.

Dramatic racial disparities

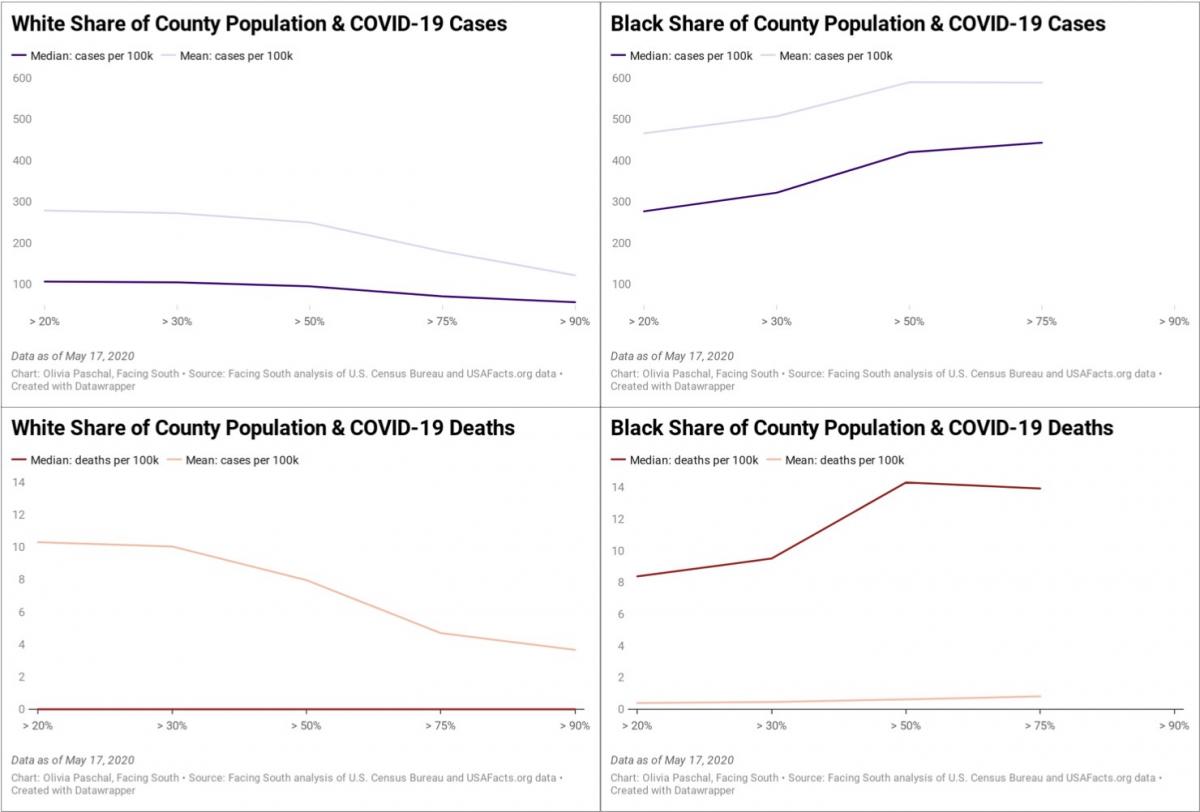

While the counties with the most concentrated outbreaks are places with prisons, where states have undertaken vigorous testing efforts, counties with the highest death rates tell a different story.

According to Facing South's analysis, the three counties in the rural South with the highest COVID-19 death rates are all majority-black counties in Southwest Georgia, where the pandemic took an early and heavy toll. Louisiana's Bienville Parish, which is more than 40 percent black, and Alabama's Tallapoosa County, nearly 30 percent black, round out the five rural Southern counties with the highest COVID-19 death rates.

Facing South also found that the median number of confirmed cases per 100,000 for majority-black counties in the rural South is more than quadruple the figure for majority-white rural Southern counties, while the median number of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 is 0 in majority-white rural Southern counties but more than 14 in their majority-black counterparts. As the black share of the population in rural Southern counties increases, the median number of confirmed COVID cases per 100,000 rises; so does the number of deaths. As the white share of the population increases, the median number of confirmed cases and deaths per 100,000 fall.

The health disparities between black and white communities in the rural South are well-documented and have deep historical roots, Zahnd said. African Americans in the rural South are more likely to live in counties with higher persistent poverty, and are more likely to report concerns over the high cost of health care. There is also a history of racism in the rural South's health care system, such as the infamous Tuskegee study, making people more reluctant to access it.

"A lot of that, quite frankly, is driven by centuries or decades of policies, potentially systemic racism, that has made it where these communities are more unhealthy because of some of those long-term effects," said Zahnd. "We need to do better for rural African-American populations to ensure this kind of thing doesn't happen again."

* For the purposes of this analysis, “rural” means any county determined by the Census Bureau to have a population that is 50 percent or more rural. County-level coronavirus data from USAFacts.org as of May 17, 2020. County-level demographic estimates are from the Census Bureau's ACS 5-year survey.

(Eric Dixon, a graduate student at Duke University, contributed to this report.)

Tags

Olivia Paschal

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Virginia. She was a staff reporter with Facing South for two years and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South's year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also led the Institute's project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive.