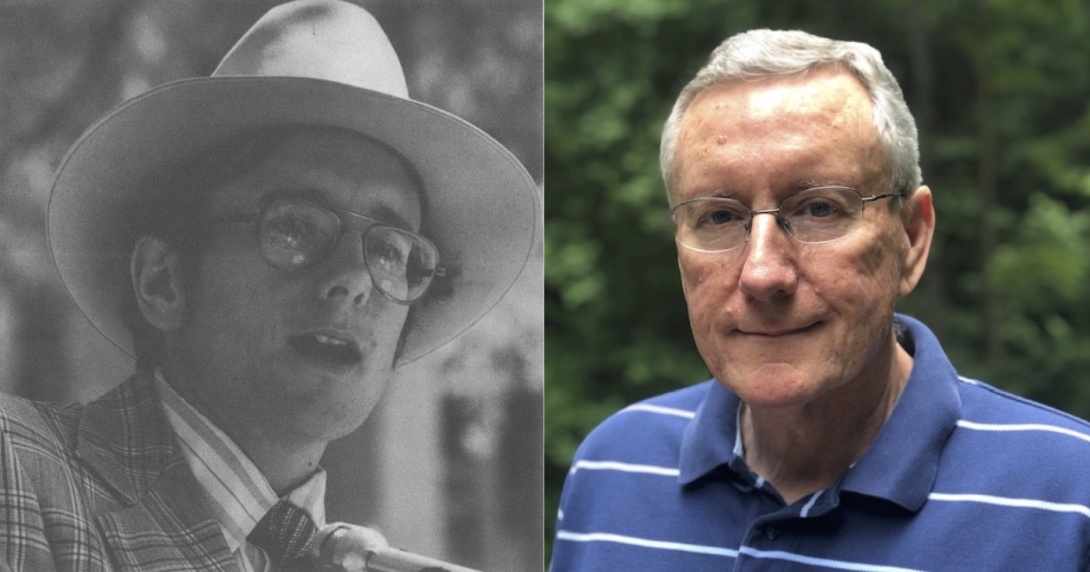

'The genie is out': Joe Ingle on 50 years of working for change in Southern prisons

Joe Ingle was interviewed in 1978 by Southern Exposure, the print forerunner of Facing South, about his prison reform work in the South. He continues to do that work today and recently talked with Facing South about the changes he's seen over the decades in both the U.S. prison system and the prison reform movement. (Photo at left by Doug Magee via Southern Exposure; photo at right courtesy of Joe Ingle.)

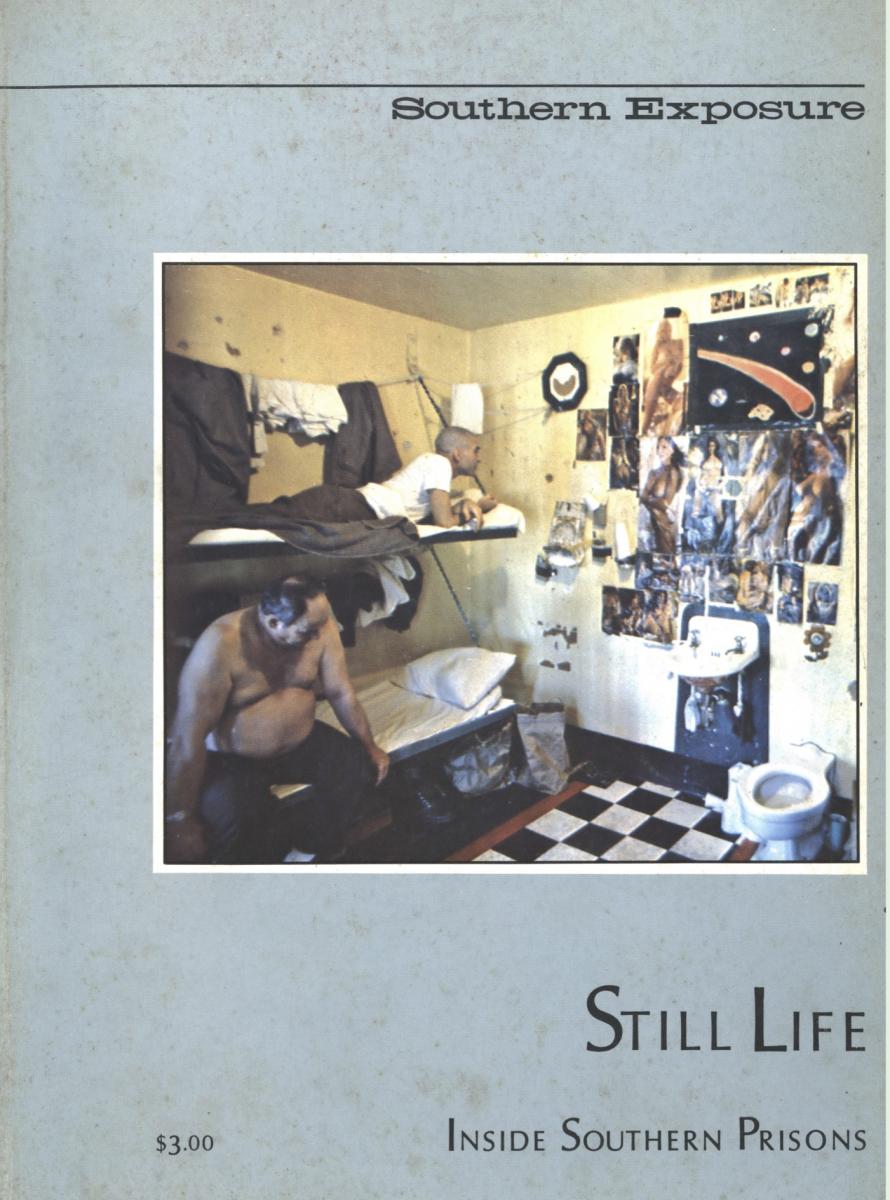

In 1978, Southern Exposure magazine, the print forerunner of Facing South, published a 116-page issue on prisons in the South. It exposed abusive conditions, quantified growing racial disparities, warned of coming prison expansion, and amplified voices calling for reform.

Pulled from the archives 42 years later, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons" serves as a time capsule offering a peek into the criminal justice system at a key turning point in U.S. history. The country was on the precipice of an era of mass incarceration that we are now struggling to escape.

Pulled from the archives 42 years later, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons" serves as a time capsule offering a peek into the criminal justice system at a key turning point in U.S. history. The country was on the precipice of an era of mass incarceration that we are now struggling to escape.

In 1978, the national prison population was around 292,000 inmates. Today it is nearly 1.5 million, not counting those in jails or on probation or parole. The prison population had already begun to rise in the 1970s when politicians from both major parties used fear and barely disguised racial rhetoric to promote increasingly punitive policies. President Nixon started the trend by declaring a "war on drugs" and delivering speeches about being "tough on crime." Under President Reagan the prison population exploded, jumping from 329,000 when he took office in 1980 to 627,000 when he left office eight years later, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. The dramatic rise in incarceration hit communities of color hardest, and they remain disproportionately impacted today.

Today there's a robust and growing people's movement pressing for reforms to the prison system and an end to mass incarceration — and some of the people involved have been in it for the long haul. They include Rev. Joe Ingle of Nashville, Tennessee, who was interviewed about his work for the 1978 issue of Southern Exposure.

A North Carolina native, Ingle graduated from St. Andrews Presbyterian College in Laurinburg in 1968 with a degree in religion and philosophy and then attended Union Theological Seminary in New York City, where he first worked with prisoners. After his time in New York, Ingle returned to the South and began working with Will Campbell and Tony Dunbar to found the Southern Coalition for Jails and Prisons in 1974 with offices in eight Southern states. Using lawsuits, advocacy, and civil disobedience, they worked to fight the death penalty and the abusive prison system. The organization folded in the early 1990s, but Ingle, a United Church of Christ minister, continues his work fighting against the death penalty, proposing alternatives to incarceration, and advocating for the rights of the incarcerated.

Ingle has been a witness to the monumental change that has happened in the past decades, both in the prison system and efforts to reform it. In this interview, which has been edited for clarity and brevity, Ingle offers his insights into the history and future of the prison reform movement.

* * *

Let's step back in time to 1978, when Southern Exposure interviewed you. At that point, how long had you been working in prison reform, and how did you get involved in that work?

In September of 1971, I was looking around for how I wanted to spend my 20 hours a week (doing community service as part of studies at Union Theological Seminary). One day, on my little fuzzy black and white TV in my tenement apartment, I watched the rebellion in Attica prison take place right before my very eyes. The prisoners had gained control of the prison and were giving press conferences. And I thought, if even 10% of what these guys were saying was accurate, I would have been angry, too.

So here I am, a white guy in East Harlem. I have never been in a prison or a jail in my life, but my friends who grew up in East Harlem deal with the cops and the criminal justice system all the time. So I decided to spend my final year of seminary visiting some kind of prison or jail.

The only one I could get into was the Bronx House of Detention. So I drove up there in my little blue Toyota for my first visit. I had my little badge on that identified me as the chaplain, and I rode the elevator up to the sixth floor. The guard lets me in, says, "Come with me." As I am walking, I look to my right, and see this really huge cage of men. We get to the end of the cell block and the guard gestures at this smaller room to the left. "That's where we have clergy and lawyer visits," he said. Now I looked in that big room, and I thought instead: "Why don't you let me in there with these guys?"

That guard looked at me like I was nuts. Clearly no one had ever asked him that, but he shrugged his shoulders and said, "All right." He went over to unlock the door to the cell block. Now remember, I'm the well-meaning white guy from the South. I stepped across that threshold, and that guard took great joy in slamming that cell door behind me. I can still feel it. As soon as that happened my instantaneous thought was this: "Oh my God, he's locked me in here with these animals." As soon as I had that thought, I realized — this is how I've been socialized.

A guy in the first bunk looks up at me and says, "Man, what are you doing here?" This guy introduced himself to me and then introduced me to everybody else. I spent that year visiting those guys, and this is what I learned. The 44 men I was visiting in that cellblock were all awaiting trial. At that time, the average length of time to trial was 18 months. That was the first stunning thing. The second was everybody I visited there was either black or Puerto Rican, except for one white guy. So that let me know how this whole thing worked racially. And the third thing I realized was that these guys are just like me. Just like me. Same hopes, same fears, just less chances because they were all poor. But we were brothers, literally brothers. So that's what I learned that first year at the Bronx House of Detention — that we were up against a monster system that was really out to do people in. It had nothing to do with justice.

In re-reading your Southern Exposure interview, what were your immediate thoughts?

I was very sad, because it meant a lot of losses. A lot of good people who've worked with me over the years are dead. A lot of prisoners I know are dead. Many have been executed, and some just died of old age. And that is all in a context where things have become progressively worse.

And that's not an abstract statement, when you know people who are actually caught in the maw of this machinery, when you know human beings who are trapped in this criminal legal system and are being destroyed. It's a very painful thing to feel and experience, even as someone who's just a visitor and has come to care for people. Especially when those people end up getting executed.

So the article reminded me where we were and where we are now. And it's like a chasm has opened up between then and now. And a lot of people have fallen into that chasm.

Having said that, I also felt great gratitude, immense gratitude, for the people who I've had the opportunity to work with through the years. I've also seen some people that I dearly love get out of prison and have successful lives. I just wish there could be more of them who have that opportunity.

You know, I've seen way too much. I really have. So I find that I don't have the patience perhaps I had in 1978 because there's been too much loss. It's time. We need to be moving toward a way of doing restorative justice in this country and away from this whole retributive model because it's such an utter failure. And to do that you have to change the economic framework. Because let's face facts, this is big money in the criminal-industrial complex. It's only when you move the money that you change the way we do justice in this country. How that happens? I don't know. But that's what needs to happen.

Give us a glimpse in the prison reform movement in those earlier years. How would you characterize the movement at that time?

To understand any movement for prison reform, you have to put it in the larger social context. So in 1978, we were still in the aftermath of the civil rights movement. Matter of fact, that's the reason so many white guys were the first people up for execution in North Carolina. James Hutchins was first up. Why was James first? Because they were not going to execute a black person first. And it was before we reached the worst context we've ever had as a society that I've lived through with Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, you know, pick your pumpkin — when we were literally throwing people in prison and jail willy-nilly. When the crime rate went up, people went for the easy solution: Lock people up. However, when you look at the crime rate, it usually correlates to unemployment rate. So when you have high unemployment, you usually have more crime. So any movement toward prison reform happens in the context of broader social issues.

As long as you have a judicial system that's sitting there based on the premise of retributive justice, you're going to have mass incarceration. There's no way around it. Because this this system has to be funded. You have to move the money to move the system.

There were things going on in the reform movement that were very creative. We had a conference here in Nashville at one of our Southern Coalition staff meetings. The National Moratorium on Prison Construction (a joint project of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee and the National Council on Crime and Delinquency) came in and we proclaimed "Jubilee Day." So in the Bible, Jubilee is when they marched around the city of Jericho and the walls came tumbling down. This is when the old Tennessee State Prison was still there. So we went out to the old prison when it was still operating and, with our trumpets and everything, we marched around the prison singing for the walls of Jericho to come tumbling down. Now, I don't know what the prison people thought, but was great. So when the walls of Jericho actually did come tumbling down at that prison as a result of the lawsuit (Grubbs v. Bradley, which won far-reaching reforms to Tennessee prisons), I always recall fondly that time we marched around blowing our trumpets.

With all the reform work that's been done over the years, why do you think we're just now having this reckoning with mass incarceration?

That's a really good question. I don't know off the top of my head if I know the answer. Because you could not have a greater contrast in today to what we were dealing with in the '70s, '80s, and '90s, back when I was getting death threats for speaking out against the death penalty. So how do you make that kind of cultural shift is the question. I really don't know what it is.

Except I think one part of it is that so many more people are affected by this monstrosity of a system now than there were previously. It has kind of percolated out to a wider audience. And with things like DNA testing, there is more and more awareness that innocent people are being sent to prison, or even to death row. Or even executed. It's like there have been these shafts of light into a mine. The shafts of light are becoming united, if you will, exposing what's actually going on.

And I think that's probably an accumulation of a lot of things, including cell phones. I mean, let's face facts: With no cell phones back in the day to see people getting killed, the police were running amok and with impunity. So I think it's been a gradual awareness and educational process that we had some role in. But also there are much larger societal factors that really opened people's eyes. And frankly, I think the younger generation has a lot to do with it. We had a (Black Lives Matter) march last week that six teenagers organized in Nashville, Tennessee, that turned out 10,000 people. Think about that for a minute. And how did they do it? They did it through social media. We're talking about high school kids. And it was peaceful. It was beautiful. Very powerful.

You're a North Carolina native who's been working in Tennessee for many years now. Why do you choose to focus your work on the South?

A lot of this is very personal. For me, it's wrapped up in race and class. Here I am growing up in North Carolina, seven years old, when I watched my father die of a heart attack. My mother moved us from Jonesville, North Carolina, to Greenville to live with my grandparents. And it was in that year that I got my first lessons on race. I remember we were in the kitchen in my grandmother's house and the bourbon was flowing. Man, I had some great storytellers in my family — my Uncle Blue, Aunt Grace, Aunt Frances. They always used the word "n-----" like it was like nothing. One night when I was 8 years old in this circle I thought, "Well, I can tell a story like my Uncle Blue can." So I told a little story and I used the word "n-----." My mother grabbed me by the arm, led me out of that room, set me down on her bed, and said "Joe, we do not use that word in this family. It is demeaning to Negros." Of course I said, "But Aunt Grace and Uncle Blue, Aunt Francis — they all say this." She replied, "I don't care what they say, you are my child, and we will not use that language in our family."

That was my first lesson on race. And little later that year, I was going downtown in the backseat of my Aunt Frances's car and there was a Black woman waiting to cross the street with this really beautiful, multicolored dress. I pointed and said, "Aunt Frances, look at that colored lady's beautiful dress." Aunt Frances leaned around, quit driving, grabbed my arm, and pulled me to her face and said, "Don't you ever call a n----- a lady again." When I came home my mom straightened me out on that, too. As unhappy as I was, I was obviously learning some lessons that year.

My final lesson was in May of 1954 after Brown v. Board of Education ordered the desegregation of public schools. Now, in the summer in Greenville, North Carolina, we had no air conditioning, so we would always walk down to the public swimming pool. So in the summer after Brown I was in my little bedroom, getting my stuff together to go down to the pool. Mom walked in and said, "What are you doing?" "I'm going swimming," I said. "It's too hot, Mom. I can't take this." She said, "You're not going swimming. They closed the pool." I was incredulous. She told me, "The people who run the city don't want to swim with Black people."

So there were three lessons — this is the way the South is. That made an early impression on me. Having said that, these are still people I loved. So when I got through seminary, I wanted to come back to where I was born and raised. I wanted to work with the people I loved, but I wanted to change them. Because this stuff can't stand. Whatever it takes, we have got to address it. If it takes going to jail, then it takes going to jail. If it takes marching, then it takes marching. Whatever it takes, we have to do it. Because the fundamental essence of the American South is still the race problem. And my friends up North, they've got their issues, too. But these are my issues. This is what I was born into. This is what I was born to deal with. This is my people.

It feels like we are living through a moment in history right now that will have big implications for criminal justice. While the Black Lives Matter movement focuses the nation's eyes on police brutality, how do you think this moment will impact prison reform?

We have to have structural change. We have to change the whole policing system in the South. When you look at law enforcement, how did it originate in the South? With slave catchers. Then after Reconstruction they were running black people into the convict lease system. So until you realize how all this stuff came about, you're not going to realize how to affect the fundamental structure. And the fundamental structure has got to go. Retributive justice has got to go. Restorative justice has to be the main model of justice in this country. That's where the victim and offender come together with a trained facilitator and solve their problem. It doesn't need a judge. It doesn't need all of the accoutrements of a court system. It's very simple, and it's being done throughout the world.

We had a conference here three years ago with Michelle Alexander, Bryan Stevenson, and Howard Zehr. We wanted to begin this discussion of re-visioning justice. It was a great conference, and when you have people like that, resources like that you can draw upon, they ought to be in front of every legislative body in this country, state and federal. And they need to be listened to. Because these are the people who are on to the fundamental issues we're encountering here. And unless you deal with the shaking of the foundations, we're going to miss this opportunity.

But it's a long haul. You've got to dig in and go to the roots. And you can't just do one thing. The police are part of a larger system. Now granted, if we set up social workers to work with the homeless and take that money out of the police budget, that gets less and less of those kind of folks in jail. That's important. But you have to understand that, as long as you have a judicial system that's sitting there based on the premise of retributive justice, you're going to have mass incarceration. There's no way around it. Because this this system has to be funded. You have to move the money to move the system.

We've talked about how the problems that we're facing have evolved. How have the solutions evolved?

Well, the fundamental need now is still the same as 1978 — restorative justice. So that hasn't changed. Having said that, we were advocating for alternatives to incarceration. Now we have got alternatives to incarceration. The problem is, when you have all kinds of incarceration, you got to tie it to a decrease in the prison system. You just can't have two parallel systems, that's just more people. We talked about doing away with the drug laws, and today we're doing that slowly. So I think we made some gains, but the reality is that the foundations are still needing to be shook. Hopefully that's what this current process will do.

It's been a very interesting year for me because in November 2018 I was with my dear friend Ed Zagorski here on death watch and he was electrocuted. (In Tennessee, death watch is a three-day period before an execution when the prisoner is moved to a cell next to the execution chamber and kept under 24-hour surveillance.) You can have a spiritual advisor. I was Ed's spiritual advisor. We had done a death watch 17 days previous to that with Ed, and he got a stay an hour and a half before his execution. So I was with him for those three days the first time around, and then three days the second time around. And then he was killed. Now, I should have never done that. I mean, if you step back and look at this, it's like being in an emotional vise and somebody is cranking it shut. You're just being squeezed and squeezed and squeezed. So after that first one, I should have stepped back and let somebody else do the second one. But I didn't, and it wiped me out. I fell into melancholia and PTSD. I just got off my last psychiatric meds two weeks ago. I haven't been into the prison in a year. I have been in trauma therapy on a weekly basis for all that time. So to have that personal experience of your own mortality, and to realize there's so little you can do — when you're in that state and look around and see all these wonderful things that are happening right now is a real lesson in humility. A lesson in just realizing, you know, this is a really cool time for a lot of issues that I care about. And it can happen without me.

I think the best generation is yours. These six teenage girls in Nashville — give me a break. It's just percolating. It's percolating all over the country. That's something I haven't seen before. I mean, when Martin Luther King was active and civil rights were huge, it was pretty much a Southern phenomenon, but this is percolating all over the nation. It's really amazing. And who knows what's going to come. Yeah. I like to think that once the genie is out of the bottle, we can't get the genie back in the bottle. The genie is out.

Tags

Grace Abels

Grace is a 2020 summer intern at the Institute for Southern Studies. She is a rising junior at Duke University studying history and journalism. She enjoys digging through the Southern Exposure archives and writing about social movements.