Descendants of Arkansas' Elaine Massacre victims push for restorative justice

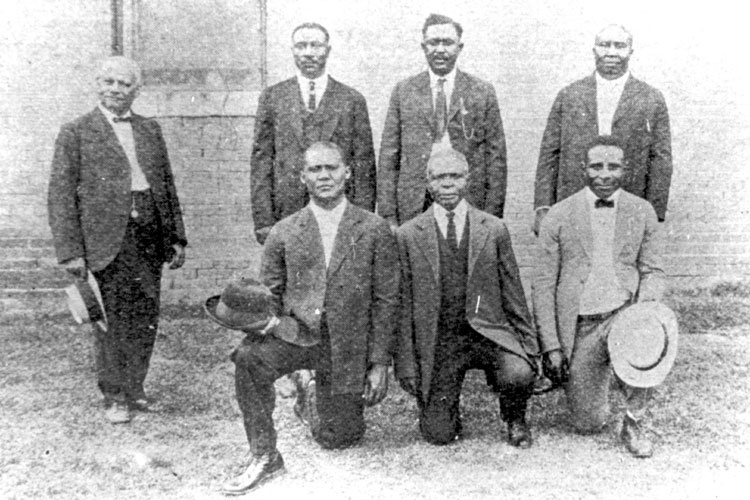

Six of the 12 Black sharecroppers sentenced to death following the Elaine Massacre pose with their lawyer Scipio A. Jones, left. Known as the Moore defendants, these six men — Ed Hicks, Frank Hicks, Ed Moore, J. C. Knox, Ed Coleman, and Paul Hall — appealed their case to the U.S. Supreme Court, resulting in a precedent-setting decision. Lisa Hicks-Gilbert, the founder of the Descendants of the Elaine Massacre of 1919 Facebook page, is a descendant of Frank and Ed Hicks. (Photo courtesy of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System.)

Late last September, hundreds of people flocked to Phillips County, Arkansas, for events held to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Elaine Massacre, when mobs of white planters and their allies killed hundreds of Black sharecroppers in retaliation for their attempt to unionize. Hundreds gathered in Helena-West Helena, where a large, privately built memorial was dedicated in the town square. In Elaine, the rural namesake of the massacre and the epicenter of the violence, people gathered at the Elaine Legacy Center for a service and healing event of their own. There were panels, sermons, and songs, the beginning of what residents hoped would be a first step towards real reckoning with how the murder of hundreds of Black residents of a small county in the Arkansas Delta has impacted the generations that came after.

Then the outsiders left. And the attention to Elaine's past did not translate into care for the town's present.

"The centennial last year left a lot of emotions up in the air. It was like a wound had been opened, a bandage had been removed from a wound, and the wound was just left open," said Ora Scaife-Truitt, a "descendant of the massacre," as Black people whose families were in Elaine and the surrounding rural townships at the time of the massacre often refer to themselves. Because there has never been a full accounting of the Black people murdered, imprisoned, and dispossessed of crops and property during the massacre, every Black family whose ancestors were in the region when it happened must assume that their family was impacted by the violence. Scaife-Truitt was born in Elaine and still lives there, volunteering with the town's children at the Lee Street Community Center.

"The documentaries have been done, the articles have been written, the books have been written," she said. "They talked to the individuals here in Elaine, talked to the elderly that would talk. But once everybody left, what were we left with?"

Scaife-Truitt and other descendants feel that the voices of those who have been most tangibly impacted are being left out of the broader conversation about the Elaine Massacre, which took place during 1919's "Red Summer" when incidents of white supremacist violence and riots took place in more than three dozen communities across the U.S. As academics continue to uncover new information about the Elaine Massacre, descendants are learning the details of the mob violence, torture, and theft used against their ancestors at the same time as the rest of the country. It has been a painful, traumatic experience for many Black families with roots in the region.

* * *

Lisa Hicks-Gilbert grew up in Elaine and attended its public schools, which have since been closed following a 2006 consolidation with a neighboring district. She first heard about the massacre 12 years ago in a Facebook post. "I thought it was fiction at first," she recalled. On her next visit with her grandmother, who lived at the time in an assisted living facility in Elaine, she asked whether she knew about it. Her grandmother closed the always-open screen door, Hicks-Gilbert remembers, and told her not to speak too loudly, worried that white residents of the living facility would overhear.

As she coaxed the story out of her grandmother over five years, Hicks-Gilbert learned that she is related to Frank and Ed Hicks, two of the dozen Black men who were convicted and sentenced to death after the massacre in sham trials. They are known collectively as the Elaine 12. Hicks-Gilbert's grandmother, who passed away late last year, made Hicks-Gilbert promise not to speak publicly about the massacre until after her grandmother's death. Like other Black Elaine residents who grew up just years removed from the massacre, she was afraid talking about it would trigger more white violence.

That silence has only recently started to break. Black people in Elaine still live and work on white-owned land. The families there now are the same ones there a century ago. The social and economic power structures of the town have not noticeably changed: Elaine and the surrounding rural townships still face continued segregation, poverty, and massive wealth disparities between their Black and white residents. In Phillips County, which is 63% Black, the poverty rate for Black people is 45% compared to just 12% for white people. According to the most recent Census estimates, 85% of those who live below the poverty line in Phillips County are Black.

Some descendants within and outside of Elaine and the surrounding townships now worry that their history and their families' trauma have become pawns for outside voices. Among those they have criticized is Mary Olson, a white Methodist minister who grew up in Wisconsin and has lived in Phillips County for two decades. She is the president of the Elaine Legacy Center, which until now has been the primary voice of the massacre victims' descendants in Elaine. Hicks-Gilbert believes that Olson — who was featured in much of the media coverage of last year's centennial commemorations and has been one of the main representatives of the Legacy Center in regional and statewide conversations about the massacre — has overstepped her position and claimed to speak for people she does not represent.

Before this year's anniversary, Hicks-Gilbert sent Olson an email asking her to reconsider her position in the community. "Many powers that be have swooped in on Elaine and taken advantage of and exploited the fact that people in Elaine are reluctant and afraid to speak out. Then there are those who come to Elaine to be the savior they think Elaine needs, instead of empowering the community to put in the work to help itself," she wrote in the email, which she shared with Facing South. "You and others need to recognize the privilege you have to use your voice without repercussion. I challenge each of you to use your voice to help address true reconciliation in healing in Elaine instead of being in constant conflict with each other to control the narrative."

Olson did not provide an on-the-record response to Hicks-Gilbert's critique of her work. The legacy center's board and staff includes Olson and several Black descendants of the massacre's victims, who have been working to gather oral histories and open a civil rights museum in the town.

"The Elaine community and the descendants do not need someone to lead us. We need someone to help us learn how to lead," Hicks-Gilbert, who currently lives in Little Rock but whose family is still in Elaine, told Facing South. To provide a space dedicated solely to empowering descendants' voices, she created a group and Facebook page called Descendants of the Elaine Massacre of 1919. This, she hopes, will create a seat at the table for her community, for descendants of the massacre's victims.

Last week, in collaboration with the Arkansas Peace and Justice Memorial Movement (APJMM), which was co-founded by Clarice Abdul-Bey, another massacre descendant, the Descendants of Elaine page hosted a week-long commemorative virtual event for the 101st anniversary. Tracing the historical arc of the massacre, it featured histories posted to the page in addition to a film screening, video messages from allies, and Zoom events.

Through the page, Hicks-Gilbert has begun to build a community of descendants focused on Elaine, but spread across the country. After the massacre, some Black families fled the Delta; some, like union leader Robert Hill, headed to Topeka, Kansas, while others went further north to cities like Chicago. Hicks-Gilbert has already met cousins whose ancestors left the state soon after the massacre; they're planning to hold a family reunion when the COVID-19 pandemic allows. She estimates that there are already more than 100 descendants actively engaged with the page.

She envisions the community she's facilitating as a way to heal and empower descendants. In the last year, Hicks-Gilbert and Scaife-Truitt have been in counseling that has helped them grapple with their own emotions of anger and fear related to the massacre. Soon, they plan to help provide that same counseling to others in Elaine experiencing similar trauma. Controversial though speaking out about the massacre and its impacts can still be, both hope they're leading by example.

"All I need to show my people [is] an example of what is possible," Hicks-Gilbert said. "Let me be your mountain until I can convince you to go over it or go around it."

* * *

It is evident to descendants of the massacre's victims that healing, restoration, and even restitution are necessary. The Elaine Legacy Center held a truth and reconciliation ceremony in 2019, and has since partnered with nationwide civil rights groups for continued conversation about reparations. "When the dreamers are martyred and murdered, then the dream has been destroyed. And it deprives so many future generations of education and other things," Lenora Marshall, a descendant who sits on the board of the Elaine Legacy Center, told Facing South.

Over the week-long virtual event hosted by the Descendants of Elaine and APJMM, descendants came together on multiple webinars to discuss what restorative justice and healing for their families, their towns, and their people could look like.

There is mounting historical evidence that in 1919, the federal troops who were called to Phillips County to restore order in fact participated in the massacre, killing Black sharecroppers and helping imprison hundreds of innocent Black people. The oral histories passed down through descendants and their families recall horrible instances of near-genocidal violence committed by white mobs: women and children placed in steel drums and thrown into the nearby lake, mothers jumping out of church windows with their children to escape gunfire, Black women agreeing to work for white families for free in exchange for letting their husbands out of prison.

"Restorative justice is basically repairing harm done," Abdul-Bey said during one of last week's virtual panels on healing and justice. And there was much harm.

In her 1920 investigative pamphlet "The Arkansas Race Riot," Black journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett calculated the approximate amount of money lost in cotton crops by the Elaine 12 and 75 other men convicted and imprisoned in the aftermath of the massacre while they sat in jail. Records show that 122 Black people were spuriously charged with crimes like accessory to murder or "night riding." In all, five white people were killed across three days of violence. But more than 200 Black people are believed to have been killed; nobody was charged in their murders.

"[The] white lynchers of Phillips County made a cool million dollars … off the cotton crop of the twelve men who are sentenced to death, the seventy-five who are in the Arkansas penitentiary and the one hundred whom they lynched outright," Wells-Barnett wrote. "[Not] one of them has ever been arrested for this wholesale conspiracy of murder, robbery and false imprisonment of these black men, nor for driving their wives and children out to suffer in rags and hunger and want!"

There are clear economic and personal losses to recoup. Descendants in Elaine say there is much to be done to ensure the town has a strong future, especially for its children. Since Elaine's public schools closed in the 2006 merger, some students travel up to an hour to and from school on back country roads, said Scaife-Truitt, the descendant who volunteers at the Lee Street Community Center.

On the panel, Scaife-Truitt said that there needed to be a real, concerted attempt at telling the truth about the massacre to the children. "Teach our history. Put it out there as it should be," she said. "Reparations look like you're going to build this community up for our youth. This is history that is ongoing, that really meant something." Teaching the history of the union, the massacre, and the Elaine 12 should be a priority, said Steven Bradley, whose ancestor Edward Coleman was also a member of the Elaine 12.

"Talk about Black truth, Black stories, Black histories, Black ancestors," said Bradley, who lives in Memphis. "Everything Elaine is suffering with is the same thing every Black community in America is suffering with. Everything is systemic."

There is also room for the descendants of white perpetrators and the descendants of Black victims to come together, Sheila Walker, whose great-uncle Albert Giles was one of the Elaine 12, told other descendants. She and J. Chester Johnson, a white poet who grew up in Southern Arkansas and learned as an adult that his grandfather had taken part in the killing, have spent the last several years on a path of conversation that has led to forgiveness and reconciliation. It's a potential model for other restorative conversations between living white and Black people whose ancestors were on either side of the massacre, so long as white people are willing to be empathetic and open to the conversation.

Other descendants want government restitution — starting with an acknowledgement from the local, state, and federal governments that they were involved in the massacre. Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge, a Republican running for governor in 2022, filmed a video for the Descendants/APJMM commemoration acknowledging the massacre. It marked the first time an official in Arkansas' executive branch has acknowledged the injustice and the loss of life that occurred in Elaine. "That helps bring some power to the descendants," Hicks-Gilbert said.

It's a step in the right direction, Abdul-Bey added, but still not enough. "If you make an acknowledgement, we need to hear from you that there are plans in the works that will lead to restorative justice," she said. On the virtual panels last week, some descendants asked for a written apology from the city and state. Hicks-Gilbert called on the state, the Elaine mayor, who is white, and the city council to come to the table and collaborate with them.

One place to start, descendants said, is serious investment in their hometown – a sustained plan for economic development and wealth-building in the Black community. "Elaine doesn't have broadband. Our water tower is rusting," and the library closes before children get back from school, said Scaife-Truitt. "I would like to see some kind of public acknowledgement," said Candace Williams, another descendant who lives in Elaine and is the executive director of the Rural Community Alliance. "Some kind of investment from our state legislature — investing in us economically, investing in our youth."

* * *

With the week of virtual events at a close, Hicks-Gilbert and APJMM are moving forward with efforts to lift up Elaine's history and direct resources back into the town. During the last state legislative session, Abdul-Bey and APJMM worked to push Senate Bill 591, which would have created a remembrance commission, a truth and reconciliation committee, and a history curriculum that engages with Arkansas' history of racist violence. The bill stalled in committee. But along with Hicks-Gilbert and the Descendants Facebook page, they're preparing to rewrite the bill and mount a second effort.

The Descendants and APJMM are also working together on a petition to exonerate all 122 Black people who were charged with crimes following the massacre. Along with the Elaine Alumni Association, Hicks-Gilbert is working on plans to repurpose the old Elaine High School building, which was gifted to the association, and use it as a community education center.

"The fact that the descendants are controlling the narrative and taking it back, that's part of the truth that's going forward," Abdul-Bey said.

Tags

Olivia Paschal

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Virginia. She was a staff reporter with Facing South for two years and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South's year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also led the Institute's project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive.