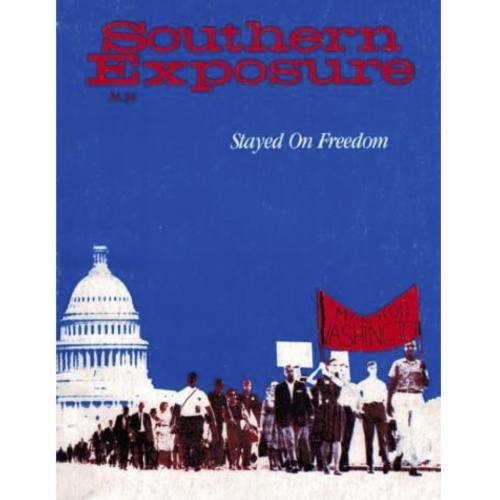

From the Archives: We needed to know more about the South

Stacks of Southern Exposure magazines, as seen in the 10th anniversary issue.

The Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, was founded 51 years ago this week. Though the COVID-19 pandemic has thus far stymied our plans for an in-person 50th anniversary celebration, we're revisiting our founding motivations, which we think resonate through the decades. Soon, we'll have more of the research, stories, oral histories, and photos that were originally published in the Southern Exposure magazine up on our website.

In 1983, for the 10th anniversary issue of Southern Exposure, some of the Institute's early staff members reflected on its founding. Below, we are reprinting the recollections of Sue Thrasher, an Institute founder and one of the original practitioners of Southern oral history, who went on to work at the Highlander Research and Education Center in Tennessee and later became an academic and educator.

As they sought to carry forward the work of the civil rights and Black freedom struggles to create a more just and democratic South, Thrasher writes, the Institute's founders believed that the movement needed to know more about the South as it was — about "'the system' ... How it worked. Who it helped, and who it hurt." And so the Institute for Southern Studies was born, a place to conduct and disseminate research in service of the South, its people, and those who want to change it for the better.

* * *

For such an advocate of oral history, I'm unfortunately a prime example of its limitations. I cannot recall the exact sequence of events that led to the formation of the Institute for Southern Studies. What I do remember — sometimes vividly, and sometimes through a glass darkly — are some of the experiences, encounters and impulses that set it in motion.

At least one of the early discussions took place sometime around 1965 in the communications office of SNCC. Julian Bond headed that office, and despite its grim task of chronicling civil-rights violations throughout the South, I remember it as a place for talk and laughter.

Our lives, at the time, were all consumed by "The Movement." Mississippi was the most obvious front, but we were, after all, creating a "new South." Opportunities for changing the world existed on every college campus and in every community. It was never necessary to question the work that had to be done, and more important, it was never necessary to question the "rightness" of what we were doing. There was an easy confidence and arrogance that came from knowing right from wrong, future from past.

The moment was all too brief. Things began to get complicated by Vietnam and the black rebellions in Northern cities. It began to dawn on us that freedom might not come with the hamburger or even with the ballot. Suddenly the New South began to appear more elusive and more complex. Perhaps it would take longer. Perhaps we needed to know more.

We talked that day in Julian's office about our need to "know more." We needed to know more about this new term, "the system." How it worked. Who it helped, and who it hurt. And who, besides us, wanted to change it. We freely imagined how much better — i.e., more informed, more organized, and more directed — "The Movement" would be if it just had a research arm that could supply it with this essential information. I don't think we were naive enough to think we would then proceed to go out and change the world. But we had smartened up enough to know that it might help.

Once the idea of a Southern research institute was planted, it hung around. A good idea with no particular plan of action. Still, the idea was occasionally tossed about with the underlying assumption that one day its time would come. In the meantime Julian was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives and then had to fight like hell to be seated because of his outspoken stand on Vietnam. Howard Romaine helped start one of the better underground papers in the country, Atlanta's Great Speckled Bird. I put in some time out of the South, for more reason than rhyme, choosing the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC. Like other Southerners who travel north, my plan was to watch carefully, cull whatever was inappropriate and bring the rest back for application on home turf. As far as I was concerned, this could mean either money or ideas!

In 1969 I came back home. IPS had given me $1,000 and the title of Associate Fellow. I cannot recall ever using the title, but the money allowed me to act as point person for beginning the organizational work on the Institute for Southern Studies. Howard, Julian and I picked up our discussions, located a sympathetic lawyer, and a year later the Institute for Southern Studies opened a small office in downtown Atlanta. By some fortuitous circumstance (in truth, Howard's persistence and cunning), our first public seminar was with Gunnar Myrdal, on his first return trip through the South since writing The American Dilemma.

But the pizzazz and prestige bestowed by an international visitor did not change the fact that the Movement we thought of ourselves as serving was breaking into many tiny pieces. We found ourselves in the odd position of trying to produce information that would help people get organized. There was a growing anti-war movement in the South, and we began to focus some of our work on the disproportionate share of military dollars flowing into the region.

For a while we maintained loose ties with the Institute for Policy Studies and the other two new "satellites," the Bay Area Institute (later to become Pacific News Service) and the Cambridge Institute (later the publisher of Working Papers). But we were always the poor cousins, and as our work began to center more and more around regional issues, institutional ties reverted to personal friendships. (To this day I am convinced that I am the mental image conjured up by Mark Raskin when he hears "The South.")

I can't recall a time along the way when any of us thought we should hang it up, have our heads examined or even seek gainful employment. Paychecks were occasionally missed, but no more often than in other social change organizations. Internally we managed to maintain mutual respect and a sense of humor, without depriving ourselves of the usual screaming matches, frosty silences, and bruised egos. We never even came close to sainthood in that regard, but we did remain friends and believed enough in each other and what we were doing to keep moving ahead.

Around us, things were going to hell in a handbasket. The progressive left had taken a decisive turn toward sectarianism, and we watched several friends march off to a shrill cadence that seemed utterly unreal. Divisions between black and white were often distant, if not downright strained. And the war in Southeast Asia had come home to campuses at Kent State, Ohio and Jackson State, Mississippi.

For some reason we persisted. Raising money was always hard, but feeling confident about the value of the work was always harder. New staff helped. First Bob Hall, and later Reber Boult and Leah Wise. We kept at the military research; Bob began to develop a corporate research project, and Leah and I, along with Jacquelyn Hall, began to pursue oral history as a means of discovering the hidden history of the South.

The turning point came when Bob decided it was time for us to start a magazine, a research report of sorts, for the Institute. Skeptical of the time, energy and money it would take, I was also mindful that we desperately needed some way to disseminate our work. And, secretly, I was happy for any opportunity for more writing and editing.

In retrospect, I think that without Southern Exposure the Institute would not have been able to remain a viable institution. The journal helped give us substance, direction, discipline and, most hated of all, deadlines. It also made us reach out for help. Well-known journalists such as Kirkpatrick Sale, Robert Sherrill, Derek Shearer and Jim Ridgeway all came to our aid that first year with investigative pieces for which they were paid our usual $50 "honorarium."

The first three issues were a pent-up fury of publishing what had been accumulating in our heads and our filing cabinets for the preceding three years — defense spending, energy and utilities, and Southern oral history. Number five was our first "what do we do now" issue and the first indication that we could lighten up and have some fun with this project.

We took turns editing that first year. Leah and I got number three and four. "No More Moanin'" nearly killed us. I have no idea how many months it took to deliver to the printer; I simply know that it took forever. It was our first book-length issue, the first with a perfect binding and the first with a slick cover. It was also our first issue without a prominent date ("We can control the numbers; we cannot control the seasons," said Bob.)

But the real importance of "No More Moanin'" was its reflection of our growing consciousness and acknowledgment that "people's words" were research tools as important as the charts, graphs, and hard data of earlier issues. Southern "voices" — of struggle, history and culture have continued to be a part of SE's research report on the region, and fortunately in that issue we had the foresight to acknowledge that it was only a beginning:

The pages that follow are bits and pieces of Southern history — determined in part by our own interest and by our access to people and information … this issue is … a beginning born out of stubborn insistence that there is more to Southern history than its mystique and magnolias.

When "No More Moanin'" finally got put to bed, I took off for Nashville. I wanted to do something completely different for a while. Five to six column-inches for the Great Speckled Bird was all I had in mind when I did a few interviews on country music. A few months later I was back at the typewriter sweating out (past deadline, of course) the lead article for our next issue, "America's Best Music." We learned to use what we had.

Ten years later Southern Exposure is still demonstrating its stubborn insistence that there is more to the South. Its pages have offered up eloquent testimonials about the right and wrong of the region, its future and its past.

When we started the Institute for Southern Studies in 1970, the easy arrogance of earlier years was gone. But we did retain the confidence — the confidence that people who believed enough in something could make it happen. The current staff of Southern Exposure has that same confidence — in themselves and their work. That's why it's still here. Lord knows there couldn't possibly be any other reason!

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.