VOICES: On UNC's troubled racial past and present

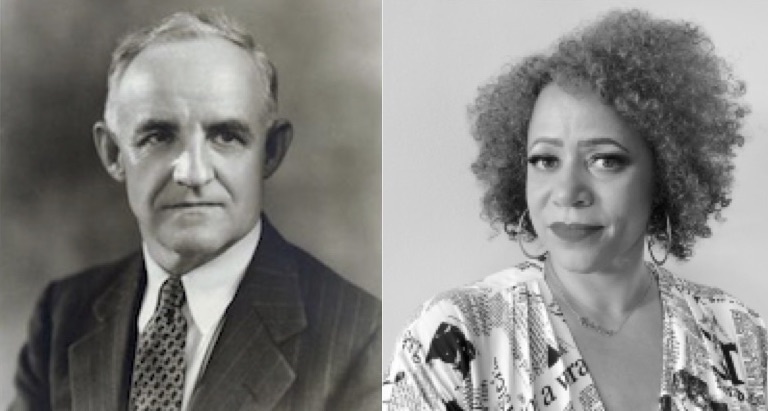

Frank Porter Graham, a history professor who led the consolidation of the University of North Carolina system in the early 1930s and served as its first president, agreed with journalist and UNC alumna Nikole Hannah-Jones that Black people are the "perfecters of democracy." (Photo of Graham via UNC's Graduate School website; photo of Hannah-Jones via the UNC Hussman School's website.)

When I heard the news earlier this year that the Board of Trustees at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill had denied Nikole Hannah-Jones tenure, I was not at all surprised, because for the past 11 years I have researched and written about the racial history of the university.

Founded in 1793, the University of North Carolina, the nation's oldest public university, has a national reputation for being a beacon of progressiveness in the South. Indeed the university's founding and guiding principles are light and liberty. However, the university has a dark history. One that is steeped in bondage, white supremacy, racial inequality and the oppression of Black people on its campus, in the town of Chapel Hill, and throughout the state of North Carolina. The university promoted slavery, Jim Crow segregation, white supremacy campaigns, and committed a multitude of other horrific injustices against Black people. And this legacy is not just the past. The past is operating in the present. Yet institutionalized racism is denied and even concealed by the university.

In January of 2010, I went to an exhibit on Blacks in North Carolina at the Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina. I saw two photographs that forever changed my perspective. One was an old black and white photograph of the first three African Americans to be admitted as undergraduates to the University of North Carolina in the fall of 1955 sitting at the Old Well. The caption said they were admitted after litigation and an appeal. A second old black and white photograph showed the first two African American graduates of UNC's law school in 1952. Its caption said they were admitted after a lengthy court battle.

I was stunned and speechless. In my seven years at UNC-Chapel Hill, as an undergraduate and as a law student, I was not taught about these men who opened the doors for me. I went looking for their stories and the court cases. I found a much larger one that intertwined the University of North Carolina, the nation's first public university, with North Carolina Central University, the nation's first public historically Black university, the state of North Carolina, the United States, and the long struggle from slavery until today for racial justice and Black freedom. One that very few people seem to know. My book, "To Drink from the Well: The Struggle for Racial Equality at the Nation's Oldest Public University" will be released on Aug. 31, 2021 (pre-order here).

I am outraged at what the university's Board of Trustees has done to Nikole Hannah-Jones. And despite the board's initial defense that it took no action, the trustee who is the chair of the University Affairs Committee, which votes on tenured faculty, raised questions about the Nikole Hannah-Jones tenure proposal and asked that it be postponed until a later time — essentially a tenure denial. Her tenure was considered again last week only after the new UNC Student Body President Lamar Richards, who sits on the Board of Trustees, insisted publicly that a special meeting be called; though they voted to grant it, she turned them down and instead will accept a tenured Knight Chair position at Howard University, a historically Black school in Washington, D.C. Though "politics" and her "non-academic background" are circulating as reasons to explain the UNC board's initial decision, the broader issue is this: The university's legacy of white supremacy, oppression of Black people and the concealment of truth is operating here and now. Even in the aftermath of the savage police murder of George Floyd when the nation is reckoning with racism.

So, the sad reality is, it should come as no surprise that this Black woman who is bold enough to speak truth to power in the 1619 Project was denied tenure and then granted it only begrudgingly. Tenure would have given her a degree of academic freedom to reveal other truths that some don't want to acknowledge or even hear.

What is surprising is that President Frank Porter Graham, the first president of the consolidated University of North Carolina system, agreed with Nikole Hannah-Jones that Black people are the "perfecters of democracy."

In a keynote speech he delivered to an integrated audience of 1,500 people in Birmingham, Alabama in 1938 at the Southern Conference for Human Welfare — an organization committed to improving social justice, civil rights, and instituting electoral reforms to repeal the poll tax in the South — President Graham said, "The black man is the primary test of American democracy and Christianity." President Graham was also a fierce defender of academic freedom. In his inauguration speech on Nov. 11, 1931, he told us: "Along with culture and democracy, must go freedom. Without freedom there can be neither true culture nor real democracy. Without freedom there can be no university. Freedom in a university runs a various course and has a wide meaning … In the university should be found the free voice not only for the unvoiced millions but also for the unpopular and even the hated minorities. Its platform should never be an agency of partisan propaganda but should ever be a fair forum of free opinion."

As Student Body President Richards said after he was sworn into the Board of Trustees on May 20, 2021, "The time has come to envision a place that we all can sit at."

Tags

Geeta N. Kapur

A native of Kenya, Geeta N. Kapur is a civil rights attorney and an activist and was the lead lawyer of Moral Mondays in Durham, North Carolina; she's also an alumna of UNC-Chapel Hill and its law school. She is the author of the book about UNC, "To Drink from the Well: The Struggle for Racial Equality at the Nation's Oldest Public University."