Civil rights attorney and author Geeta N. Kapur on pushing UNC to confront its systemic racism

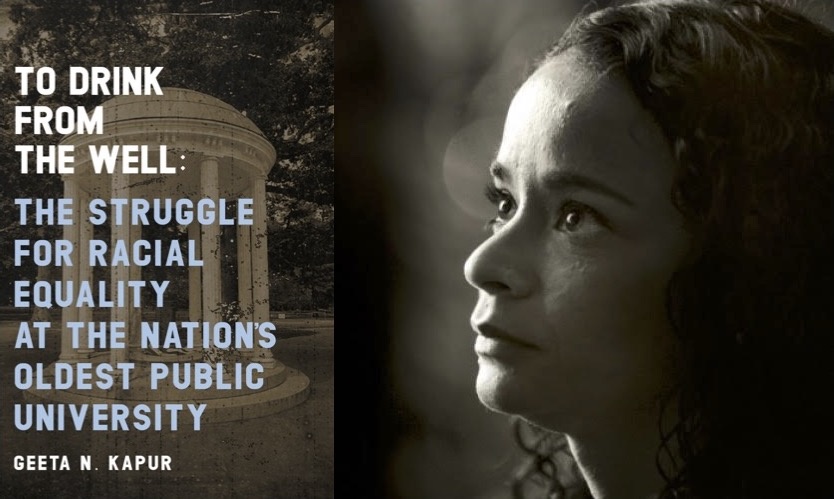

Geeta N. Kapur is the author of the new book about the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill titled "To Drink from the Well: The Struggle for Racial Equality at the Nation's Oldest Public University." (Photo of Kapur courtesy of Kapur.)

Geeta N. Kapur is a civil rights attorney in North Carolina who served as lead counsel for the Moral Monday movement. She represented hundreds of people* arrested while protesting harmful public policies championed by the state's extremist Republican General Assembly, including voter suppression bills, anti-transgender legislation, repeal of the Racial Justice Act allowing capital defendants to challenge their death sentences if they prove race was a significant factor in their sentencing, and the refusal to expand Medicaid to the state's working poor under the Affordable Care Act.

Born and raised in Kenya and of Indian, African, and European ancestry, Kapur is a double alumni of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, having received both her undergraduate and law school degrees there. But it wasn't until years after she had left Carolina that she began learning about the school's troubled racial history. Built by enslaved Black people in the 18th century, UNC didn't admit Black law students until 1951 or Black undergraduates until 1955 — and then only after protracted legal battles.

Kapur shares her alma mater's hidden history in her new book, "To Drink from the Well: The Struggle for Racial Equality at the Nation's Oldest Public University." She makes the case that if the university is ever going to truly heal from its horrific racist and white supremacist past and build a better future, it must begin by acknowledging hard truths.

Facing South recently spoke to Kapur about the book and why it's so imperative that we confront the racism embedded in America's oldest institutions. It has been lightly edited for clarity.

Your book focuses on UNC, but in some ways the school is emblematic of America as a whole. Oftentimes the same people who literally built our institutions were denied access to them — even up until a century after slavery ended.

From the records that I found, enslaved people built the first eight buildings at the University of North Carolina. Specifically, they tended to the fires, made the limestone, and then laid the bricks. The University of North Carolina was built, brick by brick, by the enslaved ancestors.

When I was writing this book, I wondered what their dreams were. I wondered what they were thinking. Most importantly, I wondered who they were, where they were from. I wondered what their cultural practices were. What stories did their moms pass down to them? I wondered about all the things that make us human. Those are all the things I wondered about, and I will forever wonder about. Those things will remain forever unknown.

In fact, their real names will remain forever unknown. There's a chart in my book of names. But, as I noted in the passage with the chart, I do not believe that any African mother would name her child Alan, Ben, Bob, David, and on and on.

These were not their birth names. These were their enslaved names, so we don't have the names of the enslaved people who built the university. All we know is that someone who was named "Bob" probably by his master, or someone the university called "Bob," made some contributions by laboring on the university buildings.

Surely they wanted education for their own children. And I just wonder, how did they deal with the fact that they are building a university that their children and their children's children will never be able to attend? That was the case for the law school until 1951 and for the undergraduate college until 1955.

It's key to note that 1955 is a very important year. 1955 was the year that the second part of Brown v. Board of Education was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Brown mandated that segregation was inherently unequal and unconstitutional. The university took the position that this ruling did not apply to colleges and universities. That's the position the university took after Brown and well into the 1960s.

There were other barriers that were put up to ensure African American students would not come to the university. After the Civil Rights Act was passed, they started requiring students to come in for an interview. In the interview, the head of admissions would often try to steer the young Black men and women to historically Black colleges and universities in a deliberate effort to keep them out of the university.

Can you say more about Brown's finding that segregation is fundamentally incompatible with equality and what that meant for UNC?

In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court found that segregation is inherently unequal — that there cannot be separate-but-equal institutions. They were ruling in the context of the public schools, but that is still true to this day about public universities and colleges. It's because the legislators are the ones who make decisions about funding for particular schools. It's still that way.

The UNC system has 17 schools. What school gets what resources, those decisions are made in part by the legislature and the Board of Governors. If the decision makers themselves are struggling with racism and white supremacy and there's a separate, segregated paradigm that they have to follow, then of course they're going to give more to the white schools than to the Black schools. And it's not just going to be more, it's going to be a lot more.

Segregation allowed racism and white supremacy to be carried out further.

One interesting aspect of the book was how the resistance to desegregating white colleges and universities began to seep into historically Black colleges and universities. For instance, James Shepard, the president of the North Carolina College for Negroes in Durham (now North Carolina Central University), did not want UNC to integrate because segregation guaranteed state funding for his own institution.

Dr. Shepard is someone that I really admire. He founded North Carolina Central University. Back then, it was the National Religious Training School and Chautauqua for the Colored Race. He started it in 1909 on land that was a trash heap. From the beginning, he had this very difficult relationship with white legislators and white benefactors.

White benefactors of the school wanted him to only teach vocational classes to Black students. He had in mind something much broader, but he had to bend to what they were asking him to do or else he wouldn't get money for the school. As time went on and the college was bought by the state and became a public school, he had to answer to the governor and to the legislators. That's a very difficult position for an African American educator to be in.

On one hand, he wants Black students educated. The research I found said that he never turned away a poor student. He wanted them to learn. He obviously wanted his school to thrive and be a sound educational institution, which requires funding from the legislature.

He was also a master diplomat. He purposely would deploy segregation as a tool to raise money for his school. He would publicly say that the price of segregation is high and it's expensive. He had to take the position that Black students should not enter the University of North Carolina. Had he taken any other position, it would have undermined funding for his school. It would have undermined the need for his school.

He was caught in a very bad situation. Some people hurled the insult "Uncle Tom" at him, but he was no Uncle Tom. He was a master diplomat of segregation. When the Gaines decision came out [a 1938 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said states providing education for white students also had to provide it for Black students], he used that to get a law school opened at his school. I think it's important that the readers know he had a very challenging, troubling relationship with the white leaders in Raleigh.

It was Durham-reared attorney Pauli Murray who actually crafted the argument that separate is inherently unequal. You mention Murray in your book and how they were denied entry into UNC because of their race, even though some of Murray's white ancestors had attended UNC and even served on the Board of Trustees.

Murray's great-great-grandfather, Dr. James Strudwick, served as a university trustee. It's important to note that he was very prominent in political circles. He and [North Carolina Supreme Court] Chief Justice Thomas Ruffin were friends. Ruffin wrote the infamous 1830 State v. Mann decision, and ruled that even when a slave was hired out the renter had complete, absolute authority over the slave.

Murray's great grandfather Sidney Strudwick and his brother Frank were alumni of the university. Murray's great aunt endowed the university with land after her death.

Oftentimes when you apply to universities legacy [family members who also attended the institution] comes up. Legacy is used in making admissions decisions. So under that model, Murray had more ties to the university than a lot of the white students who were there.

The way that I say it in my book is "it was her birthright to go there." Murray's grandmother — who I just love because she was a little feisty woman — remained justifiably bitter that her children and her grandchildren could not go to the University of North Carolina even though her aunt who raised her had left so much to the university, her father went to the university, and her grandfather was the trustee of the university. It's just troubling.

A lot of what eventually led to the integration of UNC occurred in the courts, but you make it clear that there was a very important role that the Black press played, specifically Louis Austin and the Carolina Times.

I love a lot of people in this book. I especially love Louis Austin. First, he was just an exceptional writer. I've never seen words put together the way he put them together, just to create an explosion on the paper. He closely followed higher education and segregation and the fight for desegregation. He would write columns in his paper, The Carolina Times, about what was going on so the Black community in Durham would be aware.

From what I understand, his paper was not just read in North Carolina but throughout the nation. And it was very important to him to point out the hypocrisy of state officials because back then legislators were actually on the Board of Trustees. It was a conflict of interest.

The consolidated university system made up by the women's college in Greensboro [now UNC Greensboro], N.C. State College [now N.C. State University], and the University of North Carolina had one Board of Trustees. Some of those members were legislators, so you had people who were making the laws then given the power to run the university and make decisions for it.

That infuriated Austin to no end. He also criticized Dr. Shepard, and state officials for what he characterized as ramming underfunded programs down the throat of North Carolina College for Negroes when the other existing programs were not well funded.

This point is very important because there's a connection between Chapel Hill and Durham that I didn't know existed. The connection is that all the plaintiffs that launched a legal battle came from this independent Black community in Durham, the Hayti district.

The lead lawyer, Conrad Pearson, was from Hayti. So from 1933 until 1955 when UNC was integrated, there's this relationship between Chapel Hill and Durham, and one of the key people who covered that relationship was Louis Austin. I think he also saw himself as a spokesperson for the Black community. He openly criticized the governor, legislators, and the Board of Trustees.

You mentioned Conrad Pearson. I believe the title of your book came from a quote from Pearson. Speaking of the iconic Old Well at UNC, he said, "That well over there was dug by slaves who imagine with each stroke of the pick and each scoop of the shovel, they prayed that someday their descendants would drink from the well of knowledge that was the university."

First, let me say, I did not come with this title. My editor, Robin Miura, did. At the time Miura came up with the title, I don't think she was thinking about Conrad Pearson's quote. That happened by divine intervention, by God. Pearson specifically said that enslaved people hoped and wished that their descendants would drink from the well of knowledge.

The Old Well was conceptualized in 1898. It's meant to be a symbol of democracy — the beauty of democracy. Edwin Alderman, the leader of UNC at the time, wanted to have something of beauty on the campus. He admired the round temples in the English gardens in France. In 1897 he took a picture of them, and the Old Well is based upon this.

As I say in my book, Alderman's philosophy behind the building of the little temple was the idea that democracy was crying out for beauty to give it a spiritual backbone that would defy mobs. He was directly making a reference to the Red Shirts [a white supremacist paramilitary associated with the Democratic Party] and the Ku Klux Klan.

From the very beginning, the Old Well was supposed to be a symbol of democracy. And over time, it also became known as the fountain of knowledge. That is why, to this day, students will line up on the first day of class to drink from the well. Yet, there was a deliberate effort to keep out the descendants of the people who dug the well.

Considering recent controversies at UNC like the initial denial of tenure to Black journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones and the debacle around the handling of the "Silent Sam" Confederate Statue on campus, what do you think needs to be done to ensure descendants of enslaved people have full access to the university?

In one of the opening quotes in my book, Louis Austin said that oppressors never "voluntarily lifted their heels from the neck of the oppressed and that it has only been through 'push' struggle or force that oppressed people have been able to move toward the goal of free men."

This is very true for the university. We saw it play out with Nikole Hannah-Jones. It's only after a struggle — protests that made national news and a threat of a legal struggle — that they were forced into doing the moral thing.

We look at the Silent Sam monument and it's the same thing. The university only does the moral thing after being forced to. This cycle that keeps repeating itself needs to stop. The university needs to address the fact that systemic racism permeates every part of the university. Much like our American society, there's not a part at UNC and all of its 17 schools that are insulated from systemic racism.

The university has committed horrific acts and engaged in policies to purposely oppress African American people. But they have not been willing to look in the mirror at themselves and face this history. They are willing to set up commissions and committees and make statements indicating that they want to move forward, but you can't move forward until you reckon with what's happened — and the university has not been willing to have a full reckoning.

Many of the stories that are in my book are not known to people who are deeply entrenched at the university, so there has to be truth telling. Before there's even mention of reconciliation, before we arrive at how to carry out restorative justice, the university must acknowledge the truth and stop perpetuating these picturesque pictures of this Old Well.

That is why the graphic artist who made my cover purposely made the photograph of the Old Well to be dark and dirty — because this is the university's history.

* Editor's note: The author, whose father is Moral Monday and Poor People's Campaign leader Rev. Dr. William Barber, was arrested in the protests, as was Facing South Publisher Chris Kromm.

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.