Despite public support, Southern unions still face barriers to growth

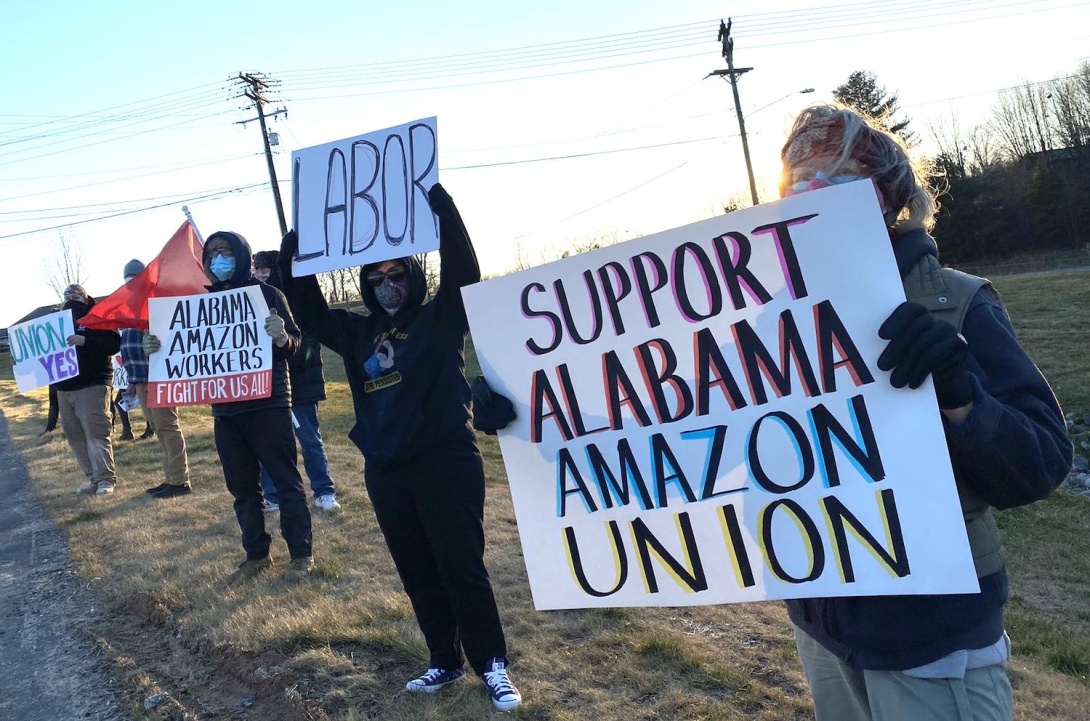

Labor allies like this group in Asheville, North Carolina, rallied across the country last year to support Amazon workers seeking to organize a union at a warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama. The National Labor Relations Board has ordered a new union election after ruling that Amazon used "dangerous and improper" tactics to dissuade workers for voting in favor of the union last April. (Photo courtesy of Support Amazon Workers.)

Public support for labor unions in the United States is at an all-time high. According to a Gallup survey last fall, 68% of U.S. residents approve of unions — the highest level of support the polling firm has registered since 1965. Pew Research similarly found last summer that 55% of U.S. adults believe unions have a "positive effect" on the country, including 69% of adults under 30.

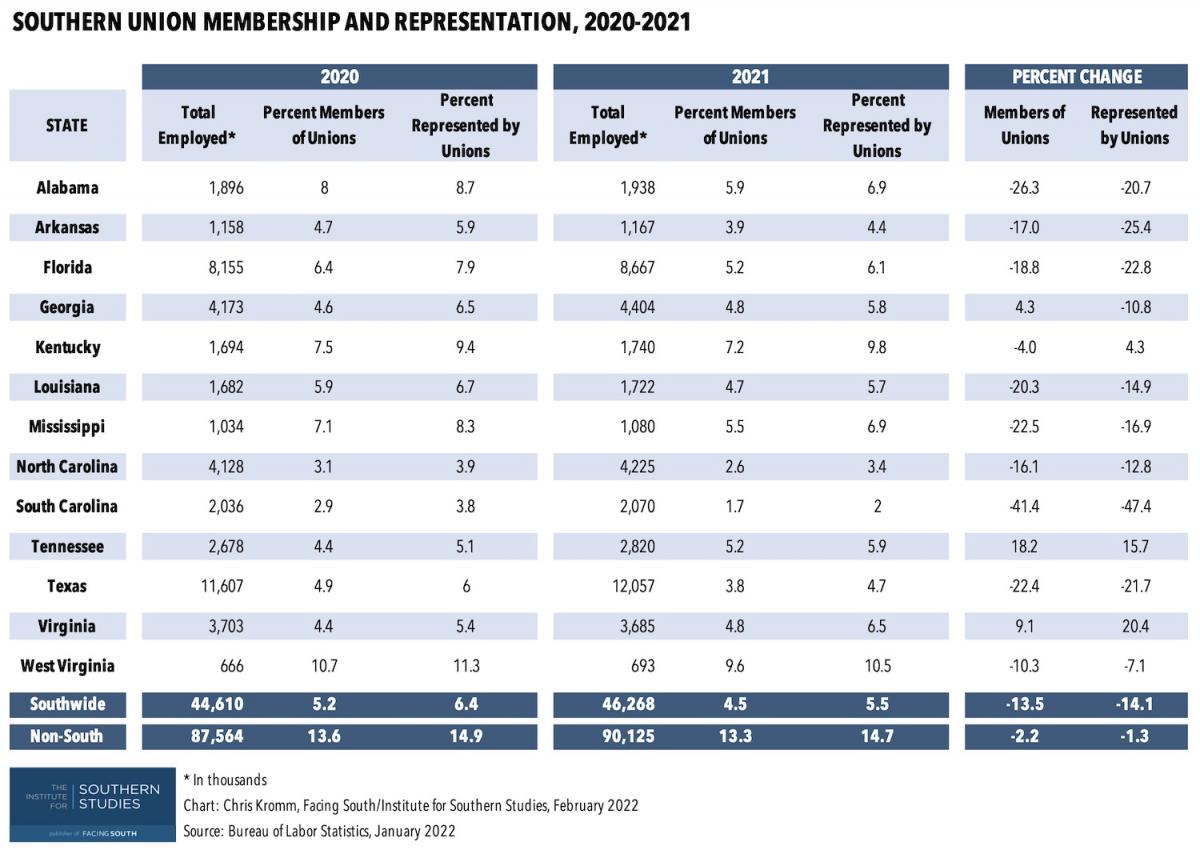

But the latest federal data on union membership shows the share of workers belonging to unions actually declined in 2021. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of unionized workers declined by more than 240,000 between 2020 and 2021, decreasing the share of hourly and salaried workers who belong to unions from 10.8% in 2020 to 10.3% last year.

The downturn was especially pronounced in the South, where sharp declines in union membership drove the nation's overall decrease: Union membership fell 13.5% in Southern states, while the decrease was only 2.2% in states outside the South.

Why, at a time when unions are increasingly popular — and labor shortages have given workers more clout in demanding higher wages and other job improvements — is membership on the decline, especially in the South? (Click on the chart below for a larger version; you can also access it here.)

The COVID effect

The apparent drop in union membership and representation in the South over the last year appears to be driven by several factors.

One of the biggest is the nature of the jobs that were lost when the COVID struck in 2020. Workers in unionized industries were more likely to stay employed during the pandemic, in part due to union protections.

The biggest job losses were in sectors where unions are more scarce, such as the hospitality and leisure industries. Nationally, almost half of the jobs in hospitality and leisure were wiped out in early 2020 by COVID shut-downs, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data; as of February 2022, about 75% have come back.

With workers in low-unionized sectors taken out of the job market in 2020, union members made up a greater share of the remaining workforce. When hotels, restaurants, and similar businesses began rehiring in 2021, the industry's less-unionized workers accounted for more of the country's workforce, driving down union percentages.

This is called the "composition effect," and it's backed up by the fact that unionization rates didn't change much between 2019 and 2021. COVID made 2020 an outlier, and as the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-backed think tank, predicts, "As the economy continues to recover and the pandemic composition effect continues to unwind, that will put downward pressure on unionization rates in 2022."

'The odds are stacked'

More than 33 million adults in the U.S. have quit their jobs since spring 2021, leading to widespread debate about "The Great Resignation" and its impact on work and the economy. As businesses have stepped up hiring and the labor market has tightened, workers have enjoyed greater bargaining power to demand improvements on the job, leading National Public Radio's Planet Money show to recast the current economic moment as "The Great Renegotiation."

But the last year has also made clear that there are limits on what employers are willing to negotiate. While pay has increased and workers have succeeded in winning other concessions from companies desperate to keep employees — including signing bonuses and increased schedule flexibility — bargaining strength hasn't translated into union organizing.

MaryBe McMillan, president of the North Carolina AFL-CIO, attributes that disconnect to the corporate and political hostility to unions and anti-labor practices, especially in Southern states.

"It's not that workers don't want unions, because they definitely do," McMillan told Facing South, citing recent poll numbers. "The problem is that it is so difficult for workers to freely exercise their right to organize. You see companies pulling out all the stops to prevent workers from forming unions."

While the recent Gallup and Pew polls showing widespread support for unions didn't break down their findings by region, earlier surveys have found adults in Southern states to have positive views of unions on par with other parts of the country.

McMillan points to cases like a Starbucks store in Memphis, Tennessee, where seven workers involved in a union organizing campaign — part of a national effort led by Starbucks Workers United to organize the coffee shops — were fired after allegedly violating company policies. The workers have filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), saying the policies were selectively enforced.

In Alabama, Amazon's aggressive anti-union tactics to stop a union drive at a warehouse outside Birmingham last April led the NLRB to order a new election, ruling Amazon's messaging was "dangerous and improper." These and other instances of employer intransigence help to explain why, despite high public support for unions and an economic climate that seems to give employees more say in decision-making, union organizing often remains elusive.

"The first election in Bessemer was very revealing of how the odds are stacked up against workers trying to organize in this country," Molly Kinder, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies low-wage work, told ABC News. "A major reason why you have this huge gap between support for unions and actual participation in unions is that the United States makes it extremely hard for workers to form a union."

Changing the rules

When President Biden was elected and Democrats won majorities in the U.S. Senate and House in 2020, labor leaders were hopeful about possibilities for changing the law to make union organizing easier.

The centerpiece of labor's agenda was the PRO Act, a sweeping piece of legislation that greatly expanded the capacity of workers to organize and heightened enforcement of labor law violations. The bill passed the House — with five Republican votes — but foundered in the Senate, largely thanks to the filibuster. Of special relevance to Southern workers seeking to organize were the PRO Act's provisions outlawing so-called "right-to-work" laws prevalent in the South, which allow workers to receive the benefits of a unionized workplace without having to join one, creating a disincentive for union membership.

That doesn't mean there hasn't been progress under the Biden administration. Biden almost immediately rescinded executive orders instituted by Trump that were viewed as hostile to federal workers. The National Labor Relations Board was retooled and is taking a more aggressive stance in cracking down on employer labor law violations. Biden also created a task force within the Department of Labor to look at how to improve support for federal employees seeking to unionize.

Biden's Build Back Better initiative also had some strong pro-labor elements, including language echoing the PRO Act that allowed for stronger penalties against employers who violate workers' rights to organize. Sen. Joe Manchin — whose state of West Virginia has the highest share of union members in the South — was, ironically, key to derailing the Build Back Better bill.

A better business model?

While labor advocates argue nothing can take the place of fundamental changes to the laws that govern union organizing, the current economic climate might compel some employers to see the benefits of unionization — or at least take a less hardline stance against labor.

As Katie Bach and Molly Kinder at the Brookings Institution note, "With workers quitting jobs at record rates and employers struggling to hire, unionized companies have a major competitive advantage: their workers stick with them. In this labor environment, union-busting may be the wrong business."

Replacing new workers can cost companies up to 20% of annual pay; for a company like Amazon, where turnover reaches 150%, failing to retain employees can translate into billions of dollars lost. While nonunion Amazon and FedEx have reported massive losses due to turnover and understaffing, shipping rival UPS, which is unionized, reported solid financials and high retention rates last year, Bach and Kinder report. In the public sector, unions have been similarly credited with lowering turnover in agencies that face a "workforce crisis," helping change management attitudes about the value of organized workers.

"The virulent anti-unionism you see among [some] management is counterproductive. In many cases, union and management can work together to improve productivity and efficiency," McMillan said. "Workers want the company to do well, too. It's in everybody's best interests."

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.