How community care can address the South's maternal mortality crisis

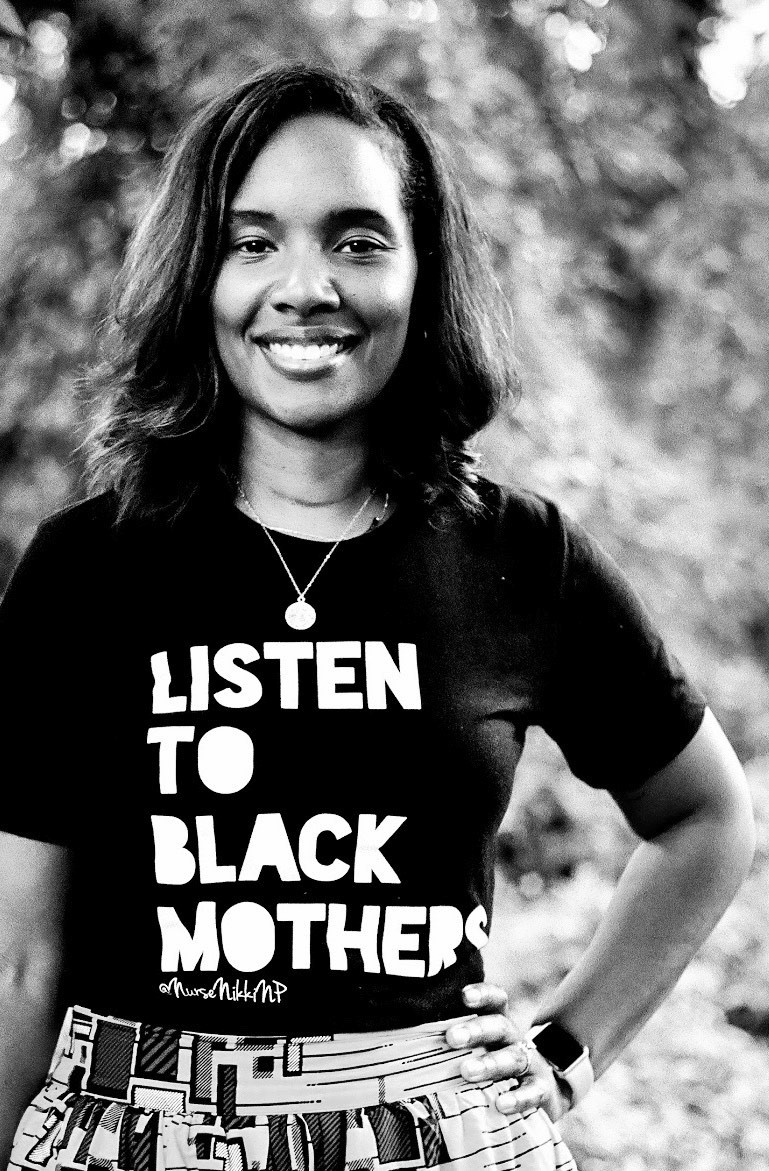

Fueled by her own experience with postpartum depression, Louisiana nurse practitioner and doula Nikki Greenaway is addressing the maternal mortality crisis by working with marginalized moms to help them better advocate for themselves. (Photo courtesy of Greenaway.)

The maternal mortality rate in the United States is 23.8 deaths per 100,000 births — the highest of any developed country. The U.S. is also the only developed country where maternal mortality rates are rising.

The crisis is especially dire in the South. As of 2018, Louisiana had the highest maternal mortality rate of any state with 58.1 deaths per 100,000 births — over three times the national rate. It was followed by Georgia with 48.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 births. Of the 10 states with the highest maternal mortality rates, six were in the South. Besides Louisiana and Georgia, they are Arkansas (37.5), Alabama (36.4), Texas (34.5), and South Carolina (27.9). The rates are even higher for Black and indigenous women.

Nikki Greenaway is a New Orleans-based family nurse practitioner, trained doula, and international board-certified lactation consultant who started a practice, Bloom Maternal Health, after her own experience with postpartum depression. She provides care for new moms through postpartum home visits to homeless shelters in under-resourced communities. The practice has since expanded to Texas as well.

Greenaway, who is Black, seeks to address the maternal mortality crisis by providing community-oriented care for her patients and empowering young parents to advocate for themselves in an often hostile health care system.

She recently spoke with Facing South about how such a model of care can keep mothers alive and thriving. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Louisiana has the highest maternal mortality rate in the country and is also a maternal care desert. Can you talk about what this means?

It is especially hard for Black women. At least 40% of the maternal deaths in Louisiana are preventable. That has decreased. But 39% of the women who give birth in Louisiana are Black women, and 68% of the women who suffer maternal deaths are Black women.

I think about our birthing hospitals. Louisiana is in the shape of a boot. Down at the bottom of the boot we have hospitals, and at the top of the boot we have hospitals. But in the middle, we do not have a whole lot of birthing hospitals. It is a very huge rural area. Over 90% of our state is considered medically disadvantaged. Especially in Lake Charles and areas like that, we are really, really in dire need of health care providers because people have to travel too far to get care. There is nowhere for them to go.

I sit on a maternal mortality review board, and we review maternal death cases. In listening to some of the stories, we'll hear this hospital didn't have this, or this hospital didn't have that, or the hospital may not be up to date on the most evidenced-based research.

There really is a deficit of knowledge sometimes among health care providers, but also in the patients that are receiving the care because they don't know what they don't know. No one has told them these things. They also don't know where to get the care that is close to them, like if they need to go to a hospital for something like a really bad headache. The provider might say, "Oh, we don't see pregnant people here." But if they don't get care that day, they may die. That's some of the situations that we are dealing with.

Can you talk about how your own experience of being a Black mom in the South has inspired your work to address the maternal mortality crisis?

I started my practice in 2012 after I had my first child. I suffered severe postpartum depression. I felt like there was nobody out there to help me navigate this space. People would say, "Oh, it's just the blues." In the Black community, I feel like it was even more of a desert for me because of the way in which we view mental health in general.

I really was inspired. My therapy for my own postpartum depression was helping other families and being the change that I wanted to see in providing the service that did not exist.

Maternal health wasn't a buzzword 10 years ago. People in the community were doing grassroots things, but we didn't have these huge local, state, and federal initiatives to help maternal health. It was kind of brushed underneath the rug.

In my own experience, even as a health care provider, I see the disparity. For example, I just had a physical a few weeks ago. I'm telling the doctor about my health because I know what my numbers should be. And the doctor was telling me I'm fine.

I had to advocate for the doctor to listen to me. No one should have to advocate this hard. We shouldn't have to advocate to save our lives. We should advocate to get a discount on some medication, but not to save my life.

I tell my patients and I tell my family members, "You are the expert on your body." The provider is the expert on the body. You have to work together for optimal care. It has to be that way. Everyone has to bring their own knowledge.

The patient has to relinquish all of the knowledge about their body and what's going on with them — truth telling. The provider has to release all the knowledge that they know about that condition — evidence-based truth telling. They have to work together. That's the only way we're going to get optimal care.

We shouldn't have to fight this hard to get care. Ten years ago, when I explained my practice to people and providers, many people asked, "Why would they need that?"

There is a six-week postpartum visit. If we were to look at some of the definitions of the baby blues, it lasts for two weeks. After that, if you still have lingering feelings of depression, anxiety, or a mood disorder, the visit is not until six weeks. What are they supposed to do until then?

The problem I found is that after six weeks they let you go. You're no longer a patient. I was trying to provide care for a mom — she contacted me for a breastfeeding home visit — but I'm not about to go to your house and help you with breastfeeding without taking your blood pressure. Postpartum hypertension is the number-one killer of postpartum women. So I take her blood pressure and it was 170. At that point, it becomes about keeping the mom alive. I contacted her obstetrician and she says, "It's been eight weeks. She's no longer our patient."

She still has pain. This didn't happen just normally — she got this from birth. This is pregnancy related. The obstetrician says she needs to go see a family doctor, and the family doctor says she needs to go see an obstetrician. They are just shuffling the patient around.

Oftentimes people are so laser focused on the baby that they miss the mother crying for help as well.

That's when I decided that I needed to step in with my practice of postpartum primary care. We help clients up to a year post birth, and then we transition them into family care where they feel confident, and we know that the lingering effects or the acute effects of pregnancy and labor have dwindled.

There's so much advocacy. Some families are just exhausted from the whole mental and physical piece of giving birth that they don't want to fight that hard. And that's where we see maternal morbidity and mortality rates increase.

Can you describe your model of community care?

Our model of care is helping families when they need it most. They usually contact us in the hospital or during pregnancy.

They're always focused on the baby, and I have to shift the mindset back to the parent. I say, "Baby is healthy, you are healing."

We do visits for two days, two weeks, and two months, and then we give ongoing technical support throughout that time through text messages or video chats. We also do home visits if necessary. That is our model of care.

We really want to change the way postpartum care is given because you're pregnant for nine to 10 months and you are in labor from 12 to 24 hours, but then postpartum is forever. How do we forget the biggest chunk of the process? That's where we truly focus and that's where we see the maternal deaths. That's where we see folks not getting what they need because everything is so focused in the hospital. When you're in the hospital, they'll take care of you for the most part, but once you go home you kind of fall off a cliff as far as health care is concerned.

We try to bridge the gap between hospital and community care. I serve as the liaison for the patient because I can get to that doctor faster than they can. And that's unfortunate. That's unfortunate that they'll take my phone call over theirs, or that they'll call me back before they call them back. I am the bridge for them to get to their provider, and we work together.

For example, I had a mom who discharged herself from the hospital because she had left her two preteens at home by themselves. She didn't have anyone to watch them while she was giving birth. But she had an elevated blood pressure in the 170s, so I went to her house and I got her doctor on the phone. I told the doctor we would have to figure out how to do care at the home because she couldn't leave the children.

Research has found that the maternal mortality crisis plagues Black women regardless of socioeconomic status, education, etc. You work with women who are very marginalized. What are the particular challenges faced by the women you work with?

The women I work with tend to be younger or teens. When you have a pregnant person entering care, if they're Black, that knocks you down. If they're a teenager, that knocks you down. If they're undocumented, that knocks you down. If they're a victim of sex trafficking, that knocks you down. If they're homeless, that knocks you down. So the people I work with are at the bottom: super marginalized folks whose voices are basically muted.

What I do is try to help them find their voice and say that you are worthy of the care that this 40-year-old white woman with private insurance is getting. You are worthy of that care because care shouldn't be based on your citizenship. It shouldn't be based on the color of your skin. It shouldn't be based on whether you have a stable home or not. It shouldn't be based on those things. It's my job to make sure that they get the care that they need when they need it the most.

I would go into the homeless shelter, and we would have a clinic date where I would see all the pregnant folks. We would work on their birth plan, but also discuss how it intertwines with their social plan. For instance, if they have another child we would talk about where that other child would stay during this time and what is going to happen afterwards.

I'm preparing them for the situation that is our health care system that mingles with our legal system. If a homeless person is coming into the hospital and they have another child, questions are asked about where they are going. If they don't have a place to go, child protective services will be called, so I'm preparing them for that situation and making sure that we have a plan in place. Sometimes I accompany them to the hospital and talk to the providers and nurses on staff and say, "This is our plan."

We have to work together as opposed to someone getting on the person and saying, "Well, I think this baby deserves this…" When they do this, they end up punishing the parent because of decisions they may have made that have resulted in a certain life situation — or criminalizing the parent.

For example, a mom that is addicted to meth or heroin — they will criticize that woman and call child protective services. But that's not what we're doing because we know that drug abuse is a health condition, and we should be treating it as such.

This person needs help, in addition to the baby. Oftentimes people are so laser focused on the baby that they miss the mother crying for help as well.

What type of progress have you seen as a result of this community care model?

We've seen an increase in breast feeding, which is awesome because breastfeeding is a privilege. When you think about an unhoused person, for instance, it's easier to give their baby a bottle. It's not as sanitary, but it's easier. With breastfeeding you actually have to pause and breastfeed your child. It has to be on your radar. When you're thinking about your next meal or where you're going to sleep, breastfeeding doesn't even come up.

We've also seen folks have less infection and being able to access care sooner. We've seen a decrease in people going to the emergency room. We've been able to help them advocate for themselves more.

In addition to the work that you're doing, what would you like to see be done on the structural level to address the maternal mortality crisis?

I really want people to act quicker. Black women, mamas — they have been dying. Too often, we have to wait for policies and procedures — and we do have to have those formalities — but I need there to be more haste to it.

The reason why we have this national platform now is because some key individuals and celebrities said they had an adverse maternal health experience. That's unfortunate, because there were other moms who also had adverse events happen. I would love for people to put more haste around it.

The pandemic has unveiled a lot of the things that were happening, and people are just now realizing it. People are just now realizing that some people don't have access to food when their children don't go to school, or that some people can't access their prenatal care because they don't have Wi-Fi.

We have to change policies that say people can only bring themselves to the visit. What happens to their other children? What happens to the baby they just had, because some practices say they can't even bring the baby that they just had to their prenatal visit?

The health care system needs to be showing empathy. They need to move away from giving generalized care and start giving personalized care. They need to listen to what their clients need — not just from a physical space, but from a social and emotional space.

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.