TESTIMONY: Environmental Justice for All Act protects vulnerable communities

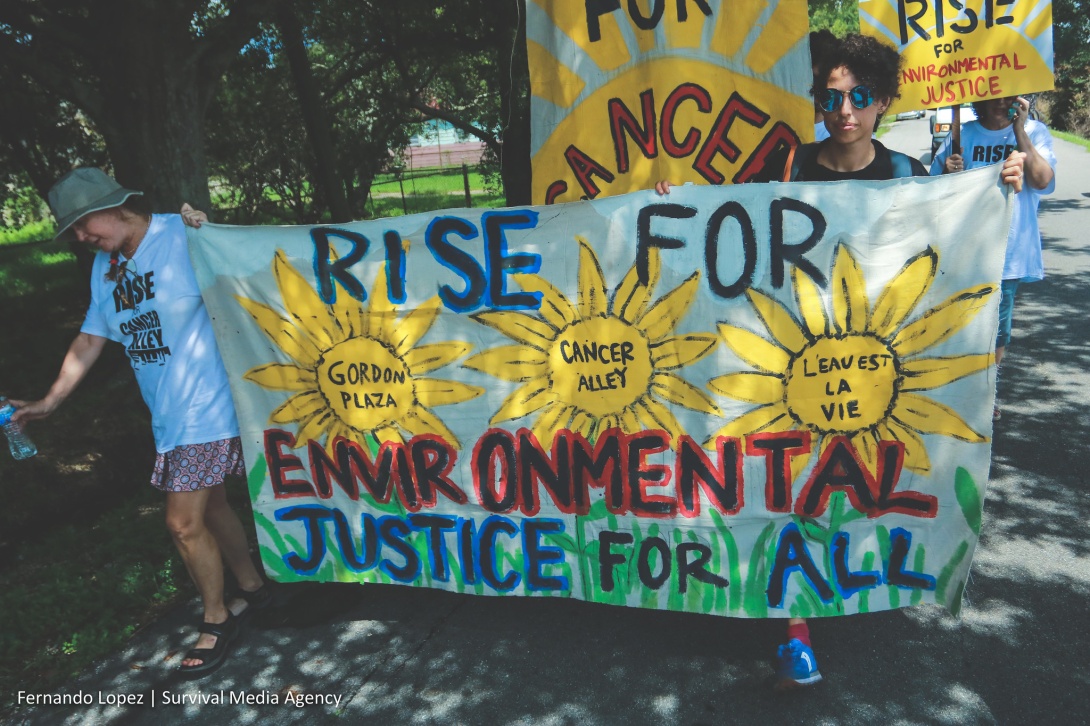

In 2018, the environmental advocacy group Louisiana Rise rallied for environmental justice in the state, where residents face numerous environmental health threats. A bill now being considered in Congress would revamp the nation's laws to better protect environmental justice communities across the South and nationwide. (Photo by Fernando Lopez/Survival Media Agency via Flickr.)

The House Natural Resources Committee, chaired by Democratic Rep. Raúl Grijalva of Arizona, held a virtual committee hearing this week on the Environmental Justice for All Act (H.R. 2021). Introduced last March, the measure amends the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to prohibit discrimination based on disparate impact and requires consideration of cumulative impacts in permitting decisions under the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act. It also requires federal agencies to provide community involvement opportunities under the National Environmental Policy Act when proposing an action that would affect an environmental justice community, defined as a place where most residents are people of color or where a substantial proportion of residents live below the poverty line, and which is subjected to a disproportionate burden of environmental hazards. In addition, the measure establishes a Federal Energy Transition Economic Development Assistance Fund using revenues from new fees on the oil, gas, and coal industries to support communities and workers during the transition away from fossil-fuel-dependent economies.

Crafted by Grijalva and A. Donald McEachin of Virginia, the latest version of the bill was introduced in the House last March. Its 27 original cosponsors include Reps. Kathy Castor of Florida, Veronica Escobar of Texas, and Gerald Connolly and Bobby Scott of Virginia. Among its 62 other current sponsors are Reps. Al Lawson, Darren Soto, and Frederica Wilson of Florida; Hank Johnson of Georgia; Bennie Thompson of Mississippi; Alma Adams of North Carolina; Steve Cohen and Jim Cooper of of Tennessee; Sylvia Garcia and Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas; and Donald Beyer and Abigail Spanberger of Virginia. All of the sponsors are Democrats. The Senate companion bill effort was led by now-Vice President Kamala Harris during the 116th Congress and is now being led by Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois.

"Today's hearing on the Environmental Justice for All Act is another important step in the legislative process to move this bill forward," McEachin said. "For too long, low-income communities, communities of color, and tribal and indigenous communities have borne the brunt of environmental degradation and injustice while being left out of crucial decision-making processes. Our bill recognizes the unique challenges and burdens individual communities face and avoids a one-size-fits-all approach. It is truly written by the people, for the people."

The following testimony in favor of the bill was presented by Amy Laura Cahn, director of the Environmental Justice Clinic at the Vermont Law School. She discussed dumping in Alabama and pipeline construction in Virginia while making a case for the legislation's transformative power. Her testimony was extensively footnoted, offering important sources for understanding the environmental justice crisis in the U.S. and how the bill would address it. Those footnotes have been changed here into endnotes. For all of the prepared testimonies and a recording of the virtual hearing, click here.

Written Testimony Regarding H.R. 2021

Environmental Justice for All Act

February 15, 2022

Amy Laura Cahn

Visiting Professor and Director, Environmental Justice Clinic

Vermont Law School, South Royalton, Vermont

I am a Visiting Professor and Director of the Environmental Justice Clinic at Vermont Law School. We practice a community-based lawyering approach to advance civil rights and environmental and climate justice.

On January 20, 2021, in issuing Executive Order 13985, President Biden called out the "unbearable human costs of systemic racism."1 Among those costs is a pattern of sacrifice zones throughout this nation where Communities of Color, Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, and low-income communities bear disproportionate environmental and climate harms, while being denied access to environmental benefits and climate solutions.2 I will speak today on the impacts of that unjust distribution of burdens and benefits–created and perpetuated by gaps in our legal system.

Section 2 of the Environmental Justice for All Act (H.R. 2021 or the Act) finds that

"[a]ll people have the right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, live free of dangerous levels of toxic pollution, and share the benefits of a prosperous and vibrant pollution-free economy."

The bill further finds that

"[t]he burden of proof that a proposed action will not harm communities, including through cumulative exposure effects, should fall on polluting industries and on the Federal Government in its regulatory role, not the communities themselves."

For far too long, this nation has denied People of Color, Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, and low-income communities — environmental justice communities — the right to a healthy environment. Our nation has saddled environmental justice communities with the burden of proving harm, neglect, and discrimination — with little redress in the face of a mountain of evidence. H.R. 2021 would fill those gaps and transform how we address environmental racism and prepare for a just transition in the face of the climate crisis.

Environmental racism is segregation imprinted onto our landscapes.

The legacies of de jure and de facto segregation are imprinted on our landscapes. Racially discriminatory housing, land use, and transportation policies have resulted in environmental justice communities breathing higher concentrations of harmful air pollutants,3 including from transportation4 and chronically substandard housing where multiple asthma triggers and lead hazards in paint, dust, soil, and water endanger residents of all ages.5 Black Americans, in particular, are exposed to more pollution from all major emission sources, including waste, energy, industrial agriculture, vehicles, and construction.6 These disparities exist nationally and across states, urban and rural areas, and all income levels.7

Race remains the strongest predictor of hazardous waste siting across the United States.8 Eighty percent of the nation's incinerators are in low-income communities and/or communities of color like Saugus, Massachusetts; Hartford, Connecticut; and Trenton, New Jersey. Residents of historically Black communities like Uniontown and Tallassee, Alabama, contend with the degraded air and water quality from Arrowhead Landfill, a 974-acre site permitted to receive up to 15,000 tons of commercial and industrial waste per day from 33 states, and the ever-expanding Stone's Throw Landfill, which continues to displace Tallassee community members and threatens to turn this historical community into yet another example of black land loss. In the words of Perry County (Alabama) Commissioner Benjamin Eaton, "if the air smells bad, you know it's bad."

The impacts of the fossil fuel industry are also particularly stark. At every stage of its life cycle, oil and gas production disproportionately harms environmental justice communities.9 More than 1 million Black people live within a one half-mile radius of natural gas facilities10 and Black and Latino/a people make up nearly two-thirds of those living within three miles of the dirtiest refineries.11 The proliferation of toxic facilities, mines, and fossil-fuel infrastructure has taken an irreparable toll on Indigenous land, cultural resources, and the health and well-being of Indigenous and Tribal communities.12

Sources of pollution come to environmental justice communities, rather than the other way around13 and residential zip code remains the strongest predictor of life expectancy overall.14 As communities of color breathe air pollution caused by white peoples' consumption,15 segregated housing and land use patterns now put environmental justice communities most at risk from extreme temperatures,16 flooding,17 and other extreme weather impacts of climate change, while inequitable resource distribution obstructs recovery from extreme weather.18 Environmental and climate impacts dovetail — heat increases the impacts of degraded air quality in historically redlined neighborhoods19 and flooding compounds the "toxic threat" of unremediated and uncontained Superfund sites.20

The impacts of environmental racism are dire and deadly.

This legacy of environmental racism has led to disparities in illness and death based on race, ethnicity, and income, including disproportionate levels of lead poisoning, asthma, diabetes, heart disease, respiratory illness, cancer, and now COVID-19.21

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare just "how profoundly the energy and environmental policy decisions of the past have failed communities of color."22 Racial disparities of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and deaths emerged early in the pandemic, and voluminous research now links air pollution exposure to those outcomes.23

That environmental injustices impact the same communities most harmed by COVID-19 is not a coincidence. It is the cumulative — and often catastrophic — impacts of discriminatory decision-making, poverty, and industrial pollution that disproportionately and adversely impact health in environmental justice communities,24 with climate change functioning as a threat multiplier.25

Inequitable distribution of resources compounds harms and stymies community-driven solutions.

Over decades, historic disinvestment has also pulled resources from communities of color to more affluent white communities.26 Such inequities persist in the distribution of federal investments into improved water quality and air quality, clean and renewable energy, and climate-resilient infrastructure. As a result, environmental justice communities are far less likely to benefit from environmental and social determinants of health that mitigate environmental burdens, including

1. Access green and open spaces27 and other resources for recreation and healthy, active living;28

2. Access to clean drinking water and sanitation;29

3. Access to affordable and clean transportation;30

4. Access to healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate food,31 including the land to securely grow one's own food;

5. Access to healthy and resilient homes and schools;32 and

6. Access to energy security,33 clean energy and energy efficiency resources,34 and the benefits of energy transition opportunities and a just transition for fossil-fuel dependent communities.35

Environmental justice communities bear the burden of proof.

In the absence of comprehensive environmental justice laws, environmental justice communities must rely on a patchwork of statutes, regulations, and executive orders insufficient to address structural inequality. Environmental protections that respond directly to the impact of environmental racism are scant,36 underenforced, and, as the last Administration has shown us, easy to roll back and even easier to ignore.37 Nor can environmental justice communities depend on civil rights enforcement to fill this gap.38

For years, residents in environmental justice communities like Uniontown and Tallassee have collected pollution data, documented health impacts, filed open records requests, disseminated know your rights information, marshaled turnout for public meetings, filed public comments and civil rights complaints, and advanced just and equitable solutions that respond to community needs — with too little response and too few available resources or remedies from the federal government.

We — and members of this Congress, in particular — have the power to shift this burden.

H.R. 2021 strengthens NEPA and the voice of environmental justice communities on major federal projects.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) has been essential in the fight against environmental racism, requiring federal agencies to involve potentially affected parties in deliberations about projects with significant environmental effects and consider potential environmental, economic, and public health impacts on environmental justice communities.39 NEPA ensures that the public's input is evaluated and considered prior to expenditures of public resources — including whether no action is the best option. Though often requiring litigation to enforce,40 NEPA operates from the principle that, when those most affected are consulted at every stage, better decisions are made.

The 2020 Trump Rule eviscerated key environmental justice provisions while prohibiting the climate impacts of a project from consideration in a NEPA analysis. The White House Council on Environmental Quality has embarked on a phased rulemaking intended to course correct. However we get there, now is the time for a stronger NEPA.

The Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)41 directs over a trillion dollars toward major projects involving highways and bridges, railways, and energy and water infrastructure projects, including funding for climate resilience, workforce development, and Superfund remediation. Many of these projects could benefit environmental justice communities; all will require robust input from surrounding residents and stakeholders. Yet, the IIJA also weakened NEPA by increasing state authority to exclude projects from NEPA review and making permanent the FAST Act, which imposes unnecessarily tight timelines for project review and authorization.42 These provisions undercut CEQ's efforts to restore NEPA and the Administration's commitments to prioritize environmental justice.

Section 14 of H.R. 2021 requires federal agencies to provide early and more robust community involvement opportunities under NEPA when proposing an action that can affect a defined environmental justice community. In this critical moment, H.R. 2021 re-centers environmental justice in the NEPA process, bolstering agencies' responsibilities to assess harmful impacts, engage environmental justice communities, and consult with Indigenous and Tribal leadership in a manner intended to better honor Indigenous sovereignty, land, and sacred sites.

H.R. 2021 fills a longstanding gap in protections for air and water quality.

As the EPA's Office of Inspector General stated in 2020, "[t]here is no precise threshold to determine when a community is overburdened[, which] means that it is often easier for a community that has seven facilities to get an eighth facility approved than for a community that has no existing facilities to get one approved."43 Limited as they are to establishing standards for and regulating individual pollutants, neither the Clean Air Act44 nor the Clean Water Act45 provide a mechanism to account for the cumulative impacts of multiple sources and uses of pollution on individual bodies and whole communities. Thus, environmental permits are routinely issued that allow regulated entities to increase levels of pollution without evaluating or accommodating adverse, cumulative, or disparate impacts on the surrounding community.46 The lack of air and water quality monitoring to understand baseline pollution levels in environmental justice communities compounds this problem.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals recently opined that "[e]nvironmental justice is not merely a box to be checked,"47 reversing a decision by the Commonwealth of Virginia to permit the construction of a compressor station associated with the Atlantic Coast Pipeline project. That decision relied on state environmental justice and energy law and policy that mandated analysis of the potential for disproportionate health impacts on the predominantly Black community of Union Hill. Even with a robust environmental justice analysis that considers direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts, NEPA still only offers a procedural framework, falling short of such substantive remedies.48

Section 7 of H.R. 2021 requires the consideration of cumulative environmental impacts in permitting decisions under the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act and provides that permits not be issued if projects are unable to demonstrate a reasonable certainty of no harm to human health after consideration of cumulative impacts. This bill would finally shift the burden onto regulators and polluters, requiring a hard look at the distribution of polluting facilities and action to protect already-overburdened environmental justice communities.

H.R. 2021 restores to communities the right to challenge environmental discrimination.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 196449 prohibits recipients of federal funding from discrimination based on race, color, or national origin, either through intentional discrimination or through actions that, while neutral on their face, have a disproportionate and adverse impact. Title VI applies broadly to recipients of funding from the family of environmental, agricultural, natural resource, land management, energy, and disaster recovery agencies. As such, Title VI should be one of the most salient tools to remedy the harms created by racial segregation and prevent future injustice as we respond to the impacts of the climate crisis.

In 2001, residents of the Waterfront South community in Camden, New Jersey, showed the power of Title VI in a briefly successful challenge to a permitting process that failed to consider the cumulative health and environmental impacts of siting a cement processing facility in an already-overburdened community of color.50 The United States Supreme Court's decision in Alexander v. Sandoval51 stopped the Waterfront South case in its tracks, barring any non-federal parties from bringing disparate impact lawsuits and placing enforcement against disparate impact discrimination solely in the hands of federal agencies.52

Title VI mandates that every federal agency ensure compliance by its funding recipients and investigate complaints of discrimination, authorizing agencies to effectuate compliance by terminating or refusing grant funding or "any other means authorized by law." In the absence of a private right of action, severe and longstanding deficiencies in civil rights enforcement and oversight have enabled funding recipients to permit waste and fossil fuel facilities and infrastructure that exacerbate racially disproportionate pollution burdens, approve transportation projects that split communities of color, and deny equitable participation of people with limited English proficiency in siting and permitting decisions.

Federal agency response to and resolution of complaints have historically been subject to delay, requiring litigation to enforce agency deadlines. Agencies, funding recipients, and the communities they are mandated to protect from discrimination lack comprehensive guidance on civil rights compliance. Complainants with firsthand knowledge have been systematically sidelined from the investigation and resolution of civil rights complaints. Agencies have refused to assert jurisdiction over complaints or make findings of discrimination, much less wield their power to withhold or delay funding, sending a message to funding recipients that compliance is optional.53

The unjust distribution of environmental, health, and climate burdens and benefits constitutes a massive failure of our nation's civil rights enforcement infrastructure. $1.2 trillion in infrastructure investments is now heading out the door, potentially outpacing a clear directive on how the Justice40 Initiative should shape the equitable distribution of expenditures54 and with insufficient mechanisms to ensure accountability in recipient decision-making and implementation.

Sections 4, 5, and 6 of H.R. 2021 would restore the right of individuals to legally challenge discrimination — including environmental discrimination — prohibited under Title VI. This would restore to communities — and the courts — the power to ensure that discrimination does not occur without consequence.

H.R. 2021 directs critical resources to address environmental racism and facilitate a just transition.

Stronger legal tools will create greater accountability and more equitable outcomes by addressing policy, planning, permitting, and enforcement decisions that perpetuate harm to environmental justice communities. These systemic changes are necessary, but not sufficient. H.R. 2021 directs critical resources for capacity building, training, research, programming, and tangible environmental benefits and puts structures in place so that environmental justice communities and fossil-fuel-dependent communities can be in the lead to proactively address conditions on the ground.

The Principles of Environmental Justice, drafted at the First People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991, responded directly to the conditions of environmental racism. These principles are rooted in holistic vision, self-determination, repair and redress, and a core belief that all people have the right to a healthy environment that enriches life. The Principles reflect the need to center in policymaking decisions the communities most impacted by environmental risks and harms and too long marginalized from the decisions that have shaped their health, welfare, and well-being.

The Environmental Justice for All Act responds to that call — through an inclusive, transparent, and community-driven process and with substantive protections that respond to community needs, fill gaps in our laws, and shift resources to where they are most needed.

Endnotes:

1. Exec. Order No. 13985, 86 FR 7009 (Jan. 20, 2021).

2. See e.g. Dorceta E. Taylor, Toxic Exposure: Landmark Cases in the South and the Rise of Environmental Justice Activism, in TOXIC COMMUNITIES: ENVIRONMENTAL-RACISM, INDUSTRIAL POLLUTION, AND RESIDENTIAL MOBILITY 6 (New York University Press 2014) (highlighting major environmental racism cases in the South).

3. See e.g., Lara P. Clark et al., National Patterns in Environmental Injustice and Inequality: Outdoor NO2 Air Pollution in the United States, 9 PLOS ONE e94431, 2 (2014), www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3988057/pdf/; Marie Lynn Miranda et al., Making the Environmental Justice Grade: The Relative Burden of Air Pollution Exposure in the United States, 8 Int'l J. Envtl. Res. Pub. Health 1755, 1768-69 (2011), www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3137995/pdf/ijerph-08-01755.pdf; Ihab Mikati, et al., Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status, American Journal of Public Health 108, 480-485 (2018), https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304297.

4. See e.g. Union of Concerned Scientists, Inequitable Exposure to Air Pollution in California: Fact Sheet (February 2019), https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2019/02/cv-air-pollution-CA-web.pdf; Inequitable Exposure to Air Pollution from Vehicles in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic: Fact Sheet, 1 (June 2019), https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2019/06/Inequitable-Exposure-to-Vehicle-Pollution-Northeast-Mid- Atlantic-Region.pdf.

5. See, e.g., Jeremy L. Mennis & Lisa Jordan, The Distribution of Environmental Equity: Exploring Spatial Nonstationarity in Multivariate Models of Air Toxic Releases, 95 Annals Soc'y Am. Geog'rs 249 (2005); Russ Lopez, Segregation and Black/White Differences in Exposure to Air Toxics in 1990, 110 Envtl. Health Persp. 289 (2002); see also Jayajit Chakraborty & Paul A. Zandbergen, Children at Risk: Measuring Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Potential Exposure to Air Pollution at School and Home, 61 J. Epidem. Cmty. Health 1074, 1074 (2007).

6. Christopher W. Tessum, et al., PM2.5 polluters disproportionately and systemically affect people of color in the United States, Science Advances, Vol. 27, no. 18, (Apr. 28, 2021); see also Tabuchi & Popovich, People of Color Breathe More Hazardous Air. The Sources Are Everywhere, NYTimes, Apr. 28, 2021.

7. Id.

8. Robert D. Bullard, Ph.D.; Paul Mohai, Ph.D.; Robin Saha, Ph.D.; Beverly Wright, Ph.D., Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty: 1987-2007, xii (2007).

9. NAACP, Fumes Across the Fence-Line, 1, 6 (Nov. 2017) https://naacp.org/resources/fumes-across-fence-line- health-impacts-air-pollution-oil-gas-facilities-african-american.

10. Id.

11. Ben Kunstman et al., Envtl. Integrity Project, Environmental Injustice and Refinery Pollution: Benzene Monitoring Around Oil Refineries Showed More Communities at Risk in 2020, 14-16 (Apr. 28, 2021), https://environmentalintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Benzene-report-4.28.21.pdf.

12. Renee McVay, Envtl. Def. Fund, Natural Gas Waste on the Navajo Nation: Updated analysis of oil and gas methane emissions shows growing problem (2021), https://www.edf.org/sites/default/ files/content/NavajoEmissionsReport2021.pdf.; Kyle Whyte, The Dakota Access Pipeline, Environmental Injustice, and U.S. colonialism, Red Ink: Int'l J. Indigenous Literature, Arts, & Humanities (Apr. 2017), https://papers.ssrn. com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2925513; R. Emanuel & D. Wilkins, Breaching Barriers: The Fight for Indigenous Participation in Water Governance, Water (2020), https://www.mdpi.com/2073- 4441/12/8/2113/htm; U.N. Special Rapporteur, End of Mission Statement by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz of her visit to the United States of America (Mar. 3, 2017), https:// www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21274&LangID=E.

13. See Paul Mohai & Robin K. Saha, Which Came First, People or Pollution? Assessing the Disparate Siting and Post-Siting Demographic Change Hypotheses of Environmental Injustice, 10 Envtl. Res. Letters 15–16 (Nov. 2015).

14. Laura Dwyer-Lindgren, Amelia Bertozzi-Villa, Rebecca W. Stubbs, Chloe Morozoff, Johan P. Mackenbach, Frank J. van Lenthe, Ali H. Mokdad, Christopher J. L. Murray, Inequalities in Life Expectancy Among US Counties, 1980 to 2014: Temporal Trends and Key Drivers, JAMA Intern. Med. (Jul. 1, 2017).

15. Christopher W. Tessum, et al., Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial–Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure, PNAS (Mar. 11, 2019).

16. See e.g. Marilyn Montgomery and Jayajit Chakraborty, Assessing the Environmental Justice Consequences of Flood Risk: A Case Study in Miami, Florida, 10 Environmental Research Letters (2015); Stacy Seicshnaydre et al., Rigging the Real Estate Market: Segregation, Inequality, and Disaster Risk, The Data Center (2018).

17. See e.g. Bill M. Jesdale, Rachel Morello-Frosch and Lara Cushing, The Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Heat Risk– Related Land Cover in Relation to Residential Segregation, 121 Environmental Health Perspectives 811-817 (2013); Jackson Voelkel et al., Assessing Vulnerability to Urban Heat: A Study of Disproportionate Heat Exposure and Access to Refuge by Socio-Demographic Status in Portland, Oregon, 15 Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018).

18. See generally, Robert D. Bullard and Beverly Wright, Race, Place, and Environmental Justice After Hurricane Katrina: Struggles to Reclaim, Rebuild, and Revitalize New Orleans and the Gulf Coast (2009); Rachel Morello Frosch, Manuel Pastor, Jim Sadd, and Seth Shonkoff, The Climate Gap: Inequalities in How Climate Change Hurts Americans & How to Close the Gap (2009); Gustavo A. Garcia-Lopez, The Multiple Layers of Environmental Injustice in Contexts of (Un)natural Disasters: The Case of Puerto Rico Post-Hurricane Maria, 11 Environmental Justice 101-108 (2018); USGCRP, Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II (2018) available at https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/downloads/NCA4_2018_FullReport.pdf.

19. Daniel Cusick, Past Racist "Redlining" Practices Increased Climate Burden on Minority Neighborhoods, E&E News (Jan. 21, 2020).

20. David Hasemyer and Lisa Olsen, A growing toxic threat — made worse by climate change, Inside Climate News (Sept. 24, 2020).

21. See, e.g., Jyotsna S. Jagai et al.,The Association Between Environmental Quality and Diabetes in the U.S., Journal of Diabetes Investigation (Oct. 2019) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7078099/, Olga Khazan, A Frightening New Reason to Worry About Air Pollution, The Atlantic (July 5, 2018) https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/07/a-frightening-new-reason-to-worry-about-air-pollution/564428; Anthony Nardone et al., Associations between historical residential redlining and current age-adjusted rates of emergency department visits due to asthma across eight cities in California: an ecological study, Lancet Planet Health (Jan. 4, 2020); New Research Links Air Pollution to Higher Coronavirus Death Rates, N.Y. Times (Apr. 7, 2020) https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/climate/air-pollution-coronavirus-covid.html; Claudia Persico & Kathryn Johnson, The effects of increased pollution on COVID-19 cases and deaths, J. Envtl. Econ. Mgmt. (Feb. 2021), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0095069621000140.

22. The Biden Plan to Secure Environmental Justice And Equitable Economic Opportunity (n.d.) https://joebiden.com/environmental-justice-plan.

23. See e.g. Wu, X. et al., Air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States: Strengths and limitations of an ecological regression analysis, Sci. Advances (2020), https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/covid-pm. See also Pallavi Pant, COVID-19 and Air Pollution: A summary of analyses, resources, funding opportunities, call for papers & more, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1UTQvW_OytC37IatMNR5qJK7qKfSylNpI2fT3pdteVZA/edit

24. Rachel Morello-Frosch et al., Understanding the cumulative impacts of inequalities in environmental health: implications for policy, Health Aff (Millwood) 30(5):879-87 (May 2011) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21555471/.

25. H. Orru et al., The Interplay of Climate Change and Air Pollution on Health, 4 Current Envtl. Health Report 504, 504 (2017).

26. Danielle M. Purifoy & Louise Seamster, Creative extractions: Black towns in White Space, Sage Journals (2020).

27. Jenny Rowland-Shea et al., The Nature Gap: Confronting Racial and Economic Disparities in the Destruction and Protection of Nature in America, Ctr. for Am. Progress (July 21, 2020), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-nature-gap/; Robert Garcia & Erica Flores Baltodano, Free the Beach! Public Access, Equal Justice, and the California Coast, 2 Stan. J. C.R. & C.L. 143 (2005); Chona Sister et al., Got Green? Addressing Environmental Justice in Park Provision, 75 GeoJournal 229 (2010); Jennifer Wolch et al., Parks and Park Funding in Los Angeles: An Equity-Mapping Analysis, 26 Urb. Geography 4 (2005); Ming Wen et al., Spatial Disparities in the Distribution of Parks and Green Spaces in the USA, 45 Supp. 1 Annals Behav. Med. 18 (2013); Dustin T. Duncan et al., The Geography of Recreational Open Space: Influence of Neighborhood Racial Composition and Neighborhood Poverty, 90 J. Urb. Health 618 (2013).

28. Penny Gordon-Larsen et al., Inequality in the Built Environment Underlies Key Health Disparities in Physical Activity and Obesity, 117 Pediatrics 417 (2006); Lisa M. Powell et al., Availability of Physical Activity–Related Facilities and Neighborhood Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics: A National Study, 96 Am. J. Pub. Health 1676 (2006); Lisa M. Powell et al., The Relationship Between Community Physical Activity Settings and Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status, 1 Evidence-Based Preventive Med. 135 (2004).

29. (Leila M. Harris et al., Revisiting the Human Right to Water From an Environmental Justice Lens, 3 Pol., Grps., & Identities 660 (2015)).

30. See e.g. Robert Bullard, Addressing Urban Transportation Equity in the United States, 31 Fordham U.L.J. 1183 (2004); Stephanie Pollack et al., The Toll of Transportation, Northeastern University Dukakis Center for Urban & Regional Policy (2013); Brian S. McKenzie Neighborhood Access to Transit by Race, Ethnicity, and Poverty in Portland, OR, 12 City & Cmty 134–155 (2013).

31. See e.g. Kimberly Morland et al., Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places, 22 Preventative Med. 23-29 (Jan. 2002); L. Powell L et al., Food Store Availability and Neighborhood Characteristics in the United States, 44 Preventive Med. 189 –195 (2007); Thomas A. LaVeist, Segregated Spaces, Risky Places: The Effects of Racial Segregation on Health Inequalities, Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies (2011). See also Alison Hope Alkon & Julian Agyeman eds., CULTIVATING FOOD JUSTICE: RACE, CLASS, AND SUSTAINABILITY 89, 93 (2011).

32. Paul Mohai et al., Air Pollution Around Schools Is Linked to Poorer Student Health and Academic Performance, 30 Health Affs. 852 (2011)).

33. Diana Hernández, Understanding 'energy insecurity' and why it matters to health, Social Science & Medicine, 167 (2016) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.029.

34. Tony G. Reames, Targeting Energy Justice: Exploring Spatial, Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Residential Heating Energy Efficiency, 97 Energy Pol'y 549 (2016));

35. Sanya Carley and David M. Konisky, The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition, Nat Energy 5, 569–577 (2020).

36. Brenda Mallory and David Neal, Practicing on Uneven Ground: Raising Environmental Justice Claims under Race Neutral Laws, 45 Harvard Env't L. R. 295, 299 (2021).

37. See e.g., José Toscano Bravo, Amy Laura Cahn, Jeannie Economos, and Rachel Stevens, Federal Dereliction of Duty: Environmental Racism Under Covid-19 (Sept. 2021) https://www.vermontlaw.edu/sites/default/files/2021- 08/Federal-Dereliction-of-Duty-Full-Report.pdf.

38. See e.g., Deloitte Consulting LLP, Final Report: Evaluation of the EPA Office of Civil Rights (Order # EP10H002058) 1–2 (noting EPA's failure to "adequately adjudicate[] Title VI complaints . . . . has exposed EPA's Civil Rights programs to significant consequences which have damaged its reputation internally and externally."); Kristen Lombardi et al., Environmental Justice Denied: Environmental Racism Persists, and the EPA is One Reason Why, Ctr. for Pub. Integrity, (2015) (noting EPA "the civil-rights office rarely closes investigations with formal sanctions or remedies," so EPA's Office of Civil Rights "appeared more ceremonial than meaningful, with communities left in the lurch."); U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, Environmental Justice: Examining the Environmental Protection Agency's Compliance and Enforcement of Title VI and Executive Order 12,898, at 2 (2016) ("U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights Environmental Justice Report") ("The [United States Commission on Civil Rights], academics, environmental justice organizations, and news outlets have extensively criticized EPA's management and handling of its Title VI external compliance program."); see also Marianne Engelman Lado, No More Excuses: Building A New Vision of Civil Rights Enforcement in the Context of Environmental Justice, 22 U. Pa. J.L. & Soc. Change 281, 295–300 (2019).

39. The White House, Memorandum for the Heads of All Departments and Agencies, Re: Executive Order on Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations (Feb. 11, 1994).

40. See e.g. Ellen M. Gilmer, Dakota Access Pipeline Loses Appeal, Fueling Shutdown Fight, Bloomberg Law (Jan. 26, 2021).

41. H.R. 3684, 117th Cong. § 11312(a) (2021).

42. 42 U.S.C. § 4370m.

43. OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GEN., U.S. ENVTL. PROT. AGENCY, FISCAL YEAR 2022 at 28 (Nov. 12, 2021) https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-11/certified_epaoig_20211112-22-n-0004.pdf.

44. Marie L. Miranda et al., Making the Environmental Justice Grade: The Relative Burden of Air Pollution Exposure in the United States, 8 INT. J. ENV'T. RSCH. AND PUBLIC HEALTH, 1755, 1755 (2011).

45. Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. § 1251(a)

46. Id. at § 1251(e).

47. Friends of Buckingham v. State Air Pollution Control Bd., 947 F.3d 68, 93 (4th Cir. 2020).

48. Id. at 310.

49. 42 U.S.C. 2000d (1964) et seq.

50. S. Camden Citizens in Action v. New Jersey Dep't of Env't Prot., 145 F. Supp. 2d 446, 503 (D.N.J.), opinion modified and supplemented, 145 F. Supp. 2d 505 (D.N.J. 2001), rev'd, 274 F.3d 771 (3d Cir. 2001).

51. Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S. 275, 292 (2001).

52. Id. at 293.

53. See supra n. 38.

54. Jean Chemnick, How states could topple Biden's Justice40 goals, E&E News (Feb. 4, 2022) https://www.eenews.net/articles/how-states-could-topple-bidens-justice40-goals.

Tags

Amy Laura Cahn

Amy Laura Cahn directs the Environmental Justice Clinic at Vermont Law School.