New federal anti-lynching law confronts ongoing legacy of racial terror

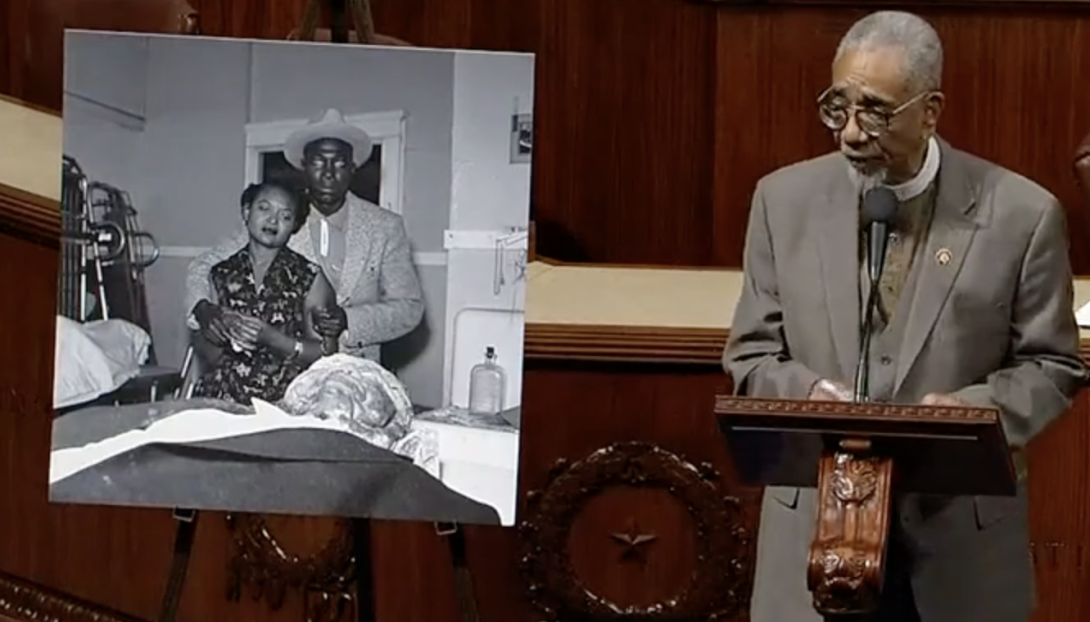

Rep. Bobby Rush stands on the U.S. House floor next to a photograph of Mamie Till and her future husband, Gene Mobley, as she views her son Emmett's brutalized body. Rush used the image to highlight the impact of racial terrorism and make the case for the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, which he sponsored. (Image is a still from C-SPAN video.)

President Biden is set to sign into law a bill that enhances penalties for lynchings, which it defines as hate crimes that result in injury or death. The Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act of 2022, which Congress passed earlier this month, makes lynching punishable by 30 years imprisonment.

"Congress is finally succeeding in taking the long overdue action by passing the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act," said Majority Leader Chuck Schumer in remarks on the Senate floor after the bill's passage. "Hallelujah. It's long overdue."

Introduced by Rep. Bobby Rush of Illinois, the bill is named after Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American from Chicago who while visiting family in Mississippi in 1955 was viciously beaten and killed by two white men. Till's murder — and his mother's decision to hold an open-casket funeral — captured national attention and exposed the horrors of white supremacy and racial violence across the South.

Decades before Till's death, lynchings of Black people had become a common practice in the South. Between the end of the Civil War in 1865 to 1950, more than 6,000 racial terror lynchings occurred across the region, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, a legal nonprofit based in Montgomery, Alabama. In 2018, EJI opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice to honor lynching victims.

According to EJI data, Mississippi, Florida, Arkansas, and Louisiana had the highest statewide rates of lynchings, while Mississippi, Georgia, and Louisiana had the highest number. Mississippi alone recorded 581 lynchings during that period.

Scholars say the racially motivated attacks, which anti-lynching crusader and journalist Ida B. Wells called the "last relic of barbarism and slavery," were designed to serve as public acts of racial terrorism that reinforced the idea of white supremacy.

"Public lynchings were warnings to the Black community," Ersula Ore, associate professor of African and African American studies and rhetoric at Arizona State University and author of "Lynching: Violence, Rhetoric, and American Identity" told the Associated Press. "It was during Reconstruction that America's modern definition of lynching as an act of white solidarity and a racialized form of social control was forged."

Historians note that lynchings were often triggered by false accusations of rape of white women. Between 1880 and 1930, almost 25% of Black lynching victims were accused of sexual assault. Lynchings were also used to repress potential economic competition and political activism in Black communities. For example, white mobs often targeted Black people who were deemed "uppity" or "insolent."

"The mob wanted the lynching to carry a significance that transcended the specific act of punishment," wrote historian Howard Smead in "Blood Justice: The Lynching of Mack Charles Parker." "The deadly act was a warning to the Black population not to challenge the supremacy of the white race."

120 years of trying

The Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act is among the more than 200 bills that have been introduced over the past century to outlaw lynching in the United States.

Congress first considered anti-lynching legislation more than 120 years ago, starting with a bill introduced in 1900 by Rep. George Henry White, a North Carolina Republican who was the only Black member of Congress at the time. White's effort was viciously attacked by The News & Observer of Raleigh, the state's largest newspaper and a promoter of white supremacy, then embraced by the Democratic Party. The bill never came up for a vote.

In the early 1900s, the NAACP launched a campaign to outlaw lynching. That effort led to another anti-lynching bill being introduced in 1918 by Rep. Leonidas Dyer, a white Republican from Missouri and a civil rights activist who was horrified by deadly racial violence in East St. Louis the previous year. The measure would have given the federal government the power to prosecute private citizens who participated in lynchings, and to fine counties that failed to prevent such violence. Though it passed the House in 1922 and had the support of President Warren G. Harding, the bill failed because of filibusters led by Southern Democrats.

Congress tried again to pass anti-lynching legislation in 1935, but Sen. Richard Russell Jr., a Georgia Democrat, held a six-day filibuster to oppose it. During the proceedings, Russell said that he was "willing to go as far and make as great a sacrifice to preserve and insure white supremacy in the social, economic, and political life of our state as any man who lives within her borders." Three years later, another anti-lynching bill was blocked by a 30-day filibuster. Subsequent measures were introduced in the 1950s and 60s but failed because of staunch opposition from Southern senators.

Then in 2018, anti-lynching legislation was introduced in the Senate itself by its three Black members: Republican Tim Scott of South Carolina and Democrats Cory Booker of New Jersey and Kamala Harris of California. The bill ultimately collapsed after the Republican-led House of Representatives failed to bring it to the floor before adjournment. Two years later, the House passed an earlier version of the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act with bipartisan support. But in the Senate, Kentucky Republican Rand Paul held up the measure, saying that it might "conflate lesser crimes with lynching."

This year Paul co-sponsored the bill after working on revising its language with Scott and Booker. He celebrated its passage, saying that it "will ensure that federal law will define lynching as the absolutely heinous crime that it is."

Modern-day lynchings

Though lynchings are nowhere near as common in the United States as they once were, the practice never ended, as The Washington Post reported last year. It pointed to the work of Jill Collen Jefferson, a lawyer and founder of the civil rights group Julian, named for the late civil rights leader Julian Bond. In 2019, Jefferson began conducting research into suspicious deaths in Mississippi and concluded that at least eight Black people had been lynched by hanging in the state since 2000. In each case she investigated, the police quickly ruled the deaths suicides, but the families believed that the victims had been lynched.

"There is a pattern to how these cases are investigated," Jefferson told the Post. "When authorities arrive on the scene of a hanging, it's treated as a suicide almost immediately. The crime scene is not preserved. The investigation is shoddy. And then there is a formal ruling of suicide, despite evidence to the contrary. And the case is never heard from again unless someone brings it up."

Mississippi is not the only state where such suspicious deaths have occurred. For example, the strange hanging death of 17-year-old Lennon Lacy in Bladenboro, North Carolina, in 2014 was quickly ruled a suicide, but serious questions remain about whether it was in fact a lynching. The North Carolina NAACP got involved in the case, leading to an investigation by the U.S. Justice Department's Civil Rights Division, the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of North Carolina, and the FBI. However, the investigation was closed in 2016 after investigators said they could find no evidence of homicide.

Another example of a modern-day lynching is the fatal shooting in 2020 of Ahmaud Arbery while he was jogging near Brunswick, Georgia. The three white men convicted of killing the 25-year-old Arbery claimed he was trespassing at a house under construction. The incident was another example of a disturbing pattern of Black people being treated with suspicion and hostility by white people during innocent activities.

Congressman Rush invoked Arbery during the discussion over his anti-lynching bill, which defines a lynching as a conspiracy to commit a hate crime that leads to death or serious bodily injury. It does not limit the definition of lynching to hanging, but also includes kidnapping and aggravated sexual abuse or an attempt to kidnap, abuse, or kill.

"Lynching is just covered in a different camouflage," Rush said. "The rope has been replaced with a shotgun and semi-automatic weapons."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.