Will courts hold Texas accountable for gerrymandering communities of color?

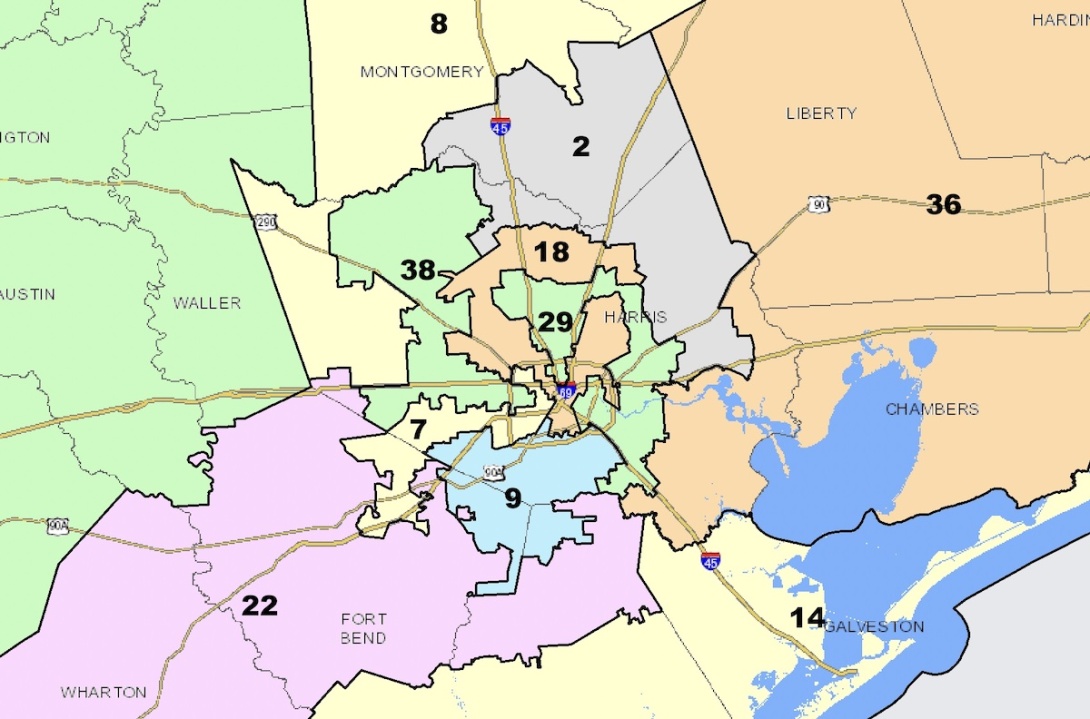

A federal lawsuit alleges that new congressional districts in Houston discriminate against Asian, Black, and Latino voters. (Map from the Texas legislature.)

The Republicans who control Southern legislatures have recently slashed the number of election districts that allow Black and Latino voters to elect their preferred candidates, and federal courts have largely refused to step in this year to protect voters of color from discrimination. But in Texas, where election districts have violated the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in every decade since the law's enactment in 1965, state and federal gerrymandering lawsuits are moving forward.

The U.S. Supreme Court, which has overturned court rulings in Alabama and other states that sought to require more VRA districts, recently declined to block Texas lawmakers from having to testify in a federal racial gerrymandering lawsuit that includes several challenges to both legislative and congressional districts.

Among other things, the lawsuits allege that the GOP violated the VRA and the U.S. Constitution by intentionally discriminating against voters of color in Dallas, Fort Worth, and West Texas. They also argue that the districts in Houston had the effect of disenfranchising Asian, Black, and Latino voters.

One of the lawsuits was brought in federal court by Common Cause Texas. "The 2020 Census data showed that people of color accounted for 95% of Texas's population increase this past decade," the lawsuit says. "But the newly enacted state House, state Senate, and Congressional redistricting plans do not reflect this reality." When the legislature drew the districts last fall, Common Cause Texas Executive Director Anthony Gutierrez described them as racial and partisan gerrymanders. "From the beginning, this Governor and the partisan state legislature were determined to solidify their political control for the next ten years at any cost to the voters," he said.

The new districts are biased in favor of Republican candidates, according to the Princeton Gerrymandering Project. Biased districts help keep state and federal lawmakers insulated from political accountability, which could contribute to further inaction on crucial issues like gun violence — even in the wake of the recent massacre of 19 schoolchildren and two teachers in the Texas city of Uvalde. The state's voters and the GOP's own campaign donors have urged action to address gun violence, but gerrymandered districts mean lawmakers don't necessarily have to worry about whether their response to gun violence is popular with voters.

Common Cause Texas and its allies argue that legislators sliced up some communities "with almost surgical precision," echoing language from a 2016 federal court ruling overturning North Carolina's restrictive new election law as racially discriminatory. Texas lawmakers, like Republicans in other states, claimed they drew the districts "race-blind." But Michael Li of the Brennan Center for Justice had testified to the Texas legislature that complying with the VRA in fact requires lawmakers to use racial data to determine if the maps are biased against voters of color.

The U.S. Department of Justice has joined on as a plaintiff in the case. The DOJ argues that, among other things, Republican legislators "intentionally eliminated a Latino electoral opportunity in Congressional District 23, a West Texas district."

The panel of three federal judges hearing the case includes Jeffrey Brown, a former Texas Supreme Court justice appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas by Donald Trump; David Guaderrama, appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas by Barack Obama; and Jerry Smith, a Ronald Reagan appointee who has long been a conservative stalwart on the rightwing 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The panel declined to block Texas' use of the districts in this year's election, but the case will go to trial this fall. And as in other redistricting lawsuits, appeals would go straight to the U.S. Supreme Court, which has a 6-3 conservative majority.

Texas will also be in state court this fall to defend some of its new state House districts in a lawsuit filed by the Mexican American Legislative Caucus. The caucus challenged districts in Cameron County, which borders Mexico and includes an overwhelmingly Latino population, for violating the state constitution's "county line rule," which generally prohibits the unnecessary division of counties in redistricting. Lawmakers split the county in two and placed half the voters in districts with neighboring counties, one of which includes mostly white, Anglo voters.

The lawsuit argues that since the county is too large for just two districts, legislators should have followed the state constitution's mandate to keep two districts within the county and put the remaining population in another district. Instead, lawmakers drew one district within Cameron County and divided up the rest of the population.

The case could ultimately be decided by the all-Republican Texas Supreme Court, which includes only two justices of color out of nine. That court is currently deciding whether to overturn the lower court's decision allowing the case to move forward.

Giving politicians free rein?

State courts in Texas and elsewhere can address gerrymandering, and their interpretations of state constitutions are final. A lawsuit similar to the Cameron County, Texas, case is pending in Kentucky, while North Carolina voting rights advocates won a big victory earlier this year when state courts ordered new districts that don't unfairly benefit one political party.

North Carolina Republicans, however, recently appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that state courts can't strike down election districts for violating the state constitution. The so-called "independent state legislature theory" relies on a highly technical reading of a provision of the U.S. Constitution that says the rules of federal elections "shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof." But the justices said in 2019 that state courts, which have the final say on state constitutions, could address partisan gerrymandering, and they've upheld voter-created redistricting commissions.

In March, the nation's highest court declined the GOP's appeal to intervene in North Carolina. However, three conservative justices dissented, while Justice Brett Kavanaugh argued it was too soon for the court to intervene but suggested that it eventually would. The justices will consider the new appeal next week, and four of them would have to vote in favor of hearing it.

Law professor Rick Hasen at the University of California, Irvine told the New York Times that, in addition to taking away the power of state courts, the theory "would also give the Supreme Court a potential excuse to interfere with presidential election results" if state courts had ruled to "give voters more protections" than they have under federal law.

In Texas and other Southern states, the defendants in racial gerrymandering lawsuits want to drastically limit the scope of the VRA. An Arkansas judge ruled earlier this year that only the DOJ can challenge election districts for violating the VRA, and Texas lawmakers have made a similar argument.

Texas has even argued that Section 2 of the VRA, which prohibits discriminatory election policies and practices, doesn't apply to redistricting. In its 2013 ruling to strike down the VRA requirement that states with a history of voting discrimination "preclear" any election changes with the DOJ, the U.S. Supreme Court assured voters that Section 2 would continue to address disenfranchisement. But its recent decisions have already begun to chip away at Section 2.

Roy Brooks, one of the plaintiffs in the federal case and a Tarrant County commissioner, told the Texas Tribune that the GOP's arguments to limit the VRA demonstrate that "those in power are determined to hold onto it by any means necessary."

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.