From the Archives: Puttin' Down Ol' Massa: Laurel, Mississippi, 1979

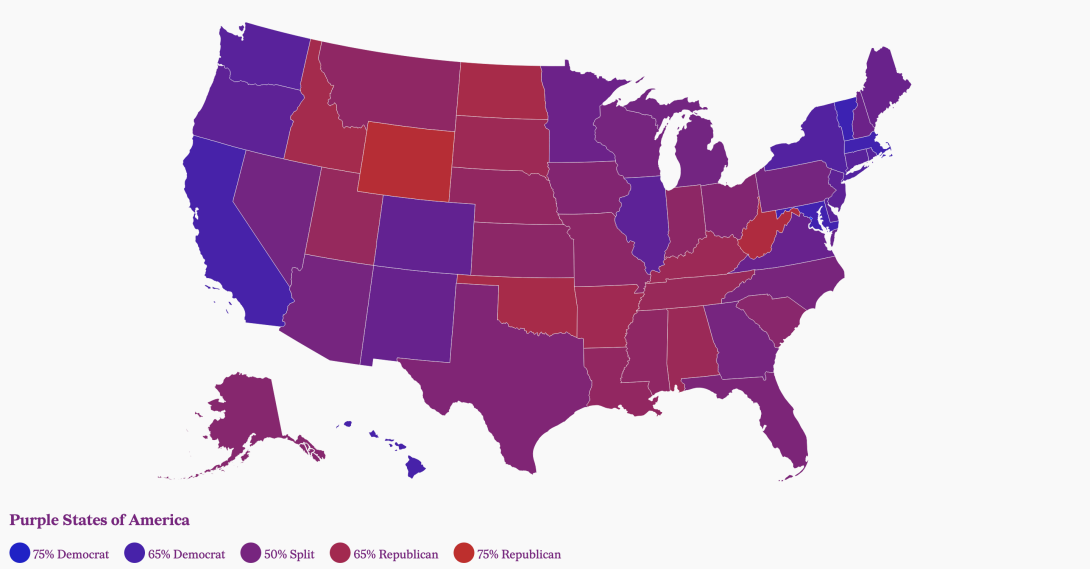

Map of 2024 elections from PurpleStatesOfAmerica.org.

Longtime labor journalist David Moberg, most recently a senior editor of In These Times, passed away on July 17 at the age of 78. Over the course of a long career, Moberg covered Cesar Chavez and the beginning of the United Farm Workers' organizing drive, labor unions' difficulties keeping up with the priorities and struggles of the multiracial, multiethnic working class, and labor's successes and failures over the last half of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st.

Moberg contributed a story on Mississippi poultry workers to Southern Exposure's 1980 anthology of labor history, "Working Lives." The story was titled "Puttin' Down Ol' Massa: Laurel, Mississippi, 1979." It recounts a union strike at a Sanderson Farms' chicken processing plant in the Mississippi city of Laurel, where workers — most of them Black — went on strike against the "plantation mindset" of the company's management. Moberg's reporting brings forward the history of racism, labor militancy, and the civil rights movement in Laurel; the Ku Klux Klan's involvement in earlier strikebreaking; and Black women's experiences working the chicken line.

We are republishing the story in Moberg's memory. You can read his obituary from In These Times here.

By David Moberg

The makeshift tent, with its fluttering, bright plastic pennants around the door, offered little refuge from the sodden heat of Mississippi in August. But it was the only shelter in the open field beyond the new cyclone fence surrounding the home of Miss Goldy chickens, the trademark chickens of Sanderson Farms. A dozen women gathered in its shade. Their best strategy was simply to sit still and hope for a breeze. But Myra Seals kept leaping up whenever she saw a car, a truck, or a passing stranger.

"Where are you going? What are you doing in there?" she shouted with imperious anger. "'Scab! I don't want to catch you in there!"

She was on guard, protecting her strike, now nearly half a year old. Six months is a long time to be on strike, with benefits that started at $30 a week now trailing off to $15. But the strikers were no strangers to lean times: when they were working, they were making $2.95 to $3.15 an hour on the disassembly line where chickens are killed, cleaned, cut up, and packaged-slightly more than the federal minimum wage of $2.90 an hour. (Mississippi, in line with much of its labor legislation, has no state minimum wage.) Oddly enough, however, the women gathered on the picket line had not gone out on strike for more money, although they would like better pay. Rather, they risked their jobs because they finally decided that working under Joe Frank Sanderson, Jr. —"Little Joe," grandson of the founder of the firm —was no longer tolerable.

"It's better since when I first came in 'cause we got a union, said Pressie Clayton, 60, an eight-year veteran, "but everywhere else is so much better than this. That's what I don't like. For break they weren't giving us what they promised. They promised ten minutes twice a day and gave us four or five minutes and sometimes only once a day. We want more. We want sick leave. Now you just take your own time. And we want to go to the bathroom when you have to." The rule at Sanderson Farms was only three toilet breaks a week outside of normal breaks. It was not only irritating and demeaning, a symbol of the hard regimen within the factory, but a potential health problem There were the inevitable horror stories, some recalled with a darkly comic edge (the woman with diarrhea who shit in her pants), others more clearly painful (such as the pregnant woman who was denied toilet break despite her pleading and then had a miscarriage the following day).

The work was hard and had been getting harder: hanging up 140 live chickens on the line each minute (up recently from 100 a minute cutting a major incision in 60 chickens a minute; "venting" (making cut and pulling out the chicken's guts) 20 to 24 a minute; completely cutting up 5 whole chickens a minute.

The arbitrary and strict rules, the low pay, the safety hazards, the hard work, and the casual violation by management of their feeble contract weren't all that angered the workers at Sanderson Farms. “We really feel it's a question of human dignity," Gloria Jordan, 46, vice-president of the local union, said. "They didn't have no manner of talking to you like human beings. They order you in a loud tone of voice. They don't ask you. They don't care if you're hurt."

"All they're concerned about it seems is those chickens and not employees," Alice Musgrove, 41, mother of seven and a six-year employee at Sanderson Farms, said, "One of my children called to tell me one day that another of my children was sick. They didn't tell me right away about the call. When I said I was going home, because had lost one child when was working on another job, the foreman was saying I shouldn't be so concerned about my own blood. They tell me, 'What's more important, your child or your job?'”

Laurel is the county seat of an unusual piece of the south that dramatically contrasts some of the most progressive and most reactionary sides of the region's history. During the Civil War, Jones County broke away from the Confederacy and declared itself the Free State of Jones, its sovereignty defended by a guerilla army under the leadership of Newt Knight. Later, the county had the only substantial socialist vote in the state and even elected local socialists to office, according to Ken Lawrence, a veteran organizer and labor historian.

It was also the site of the first CIO organizing victory in Mississippi, at the local Masonite plant.

At the same time, it is in the heart of Ku Klux Klan country. In the late 1940s the Klan was a leading agent of the drive to break the CIO in Jones County. After a celebrated trial in 1948, a black man, Willie McGee, was executed for rape, despite the efforts of his attorney, Bella Abzug. Newt Knight's grandson, the descendant of Knight's relationship with a black woman, was tried on a charge of miscegenation. “It is obvious that they were waging war against that tradition,” Lawrene says.

More recently, Jones County, one of the more unionized counties in the state in the past, has been the scene of militant strikes and organizing efforts among poultry workers and the Gulf Coast pulpwood workers. In 1967 a bitter wildcat strike at the 2,300-worker Masonite plant dragged on for seven months. Hundreds of workers were fired for fighting against work-rule changes by the new management that undercut the workers' considerable shop floor power. Serious racial tensions accompanied the strike, Jim Youngdahl, then attorney for the union, recalls, as the Klan tried to take over the strike and as many blacks crossed the picket line. Management's success in breaking that strike dealt a serious blow to unionism in the area.

During the sixties, the civil rights movement didn't affect Laurel as deeply as many other towns in the state, local activists now say, but the specter of violence against civil rights workers was glaringly evident. Laurel was home to some Klansmen, including the notorious Sam Bowers, accused of killing the three civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney in 1964. Local people also recall vividly the later killing of NAACP leader Vernon Dahmer. "Nobody forgets that," organizer Kim Pittman says. "They shot him up and burned his house. You don't have to do that more than once every twenty-five years to frighten people." One of the men arrested in connection with the Dahmer murder (and later acquitted of the chargers) was Charles Noble. Today he is a supervisor at the Sanderson Farms plant in Laurel. Nearly all of the foremen and supervisors there are white men. Nearly all of the workers are black women.

“You start talking to them about a white man and they're just scared,” Gloria Jordan says of many of her fellow workers. "They often say, “Girl you better be careful when you talk to that white man or you'll be be burned out tonight!' Having Charles Noble, a Klansman, in there affects a lot of people.”

So the two traditions of Jones County and of the South come up against each other at Sanderson Farms, even if few workers there would respond to a call to "remember Newt Knight!" But William Magee, 39, now president of the local, was urged to start a union by his father-in-law, who was a union man at Masonite, the original CIO stronghold. Virtually nobody at the Sanderson Farms plant in 1972 had ever belonged to a union, but they were upset with the arbitrary authority of management. A minister made contact with a union —nobody seems to remember how it happened to be the International Chemical Workers —but the workers organized themselves, with inadvertent assists from the owners.

Joe Frank Sanderson, Sr., fought the union vigorously but lost. Just before the balloting, Magee recalls, Sanderson called all the workers to a meeting. In a commonplace antiunion tactic in the South, he had a table covered with groceries. Standing before them in his white three-piece suit, he explained how one could buy all of these groceries with a year's union dues. When he finished, the workers dutifully applauded, but their real sentiments were different. "Man," one of them whispered to Magee, "maybe if we get a union in here I can get one of them three-piece suits."

D.R. Sanderson founded Sanderson Farms as a poultry growing and processing business in 1951 after a career as a salesman and a retail feed dealer. Gradually the business expanded to include hatcheries, poultry farms, feed mill, and three plants capable of processing 180,000 chickens a day. As of 1977 its assets had grown to $8 million, its annual sales were $50 million, and its payroll numbered 1,200, making it one of the biggest poultry companies in Mississippi, which ranks fifth among the fifty states in broiler production. The family owns 80 percent of the stock.

In an industry with a reputation for low wages and bad working conditions, estimates of the extent of unionization run from only 30 percent (a United Food and Commercial Workers Union representative) to a "majority" (the Mississippi Poultry Association), still higher than many Southern industries. Sanderson Farms wages are wage. Union plants average around $3.75 to $4 an hour for the same typical for nonunion plants: around $3.10, or just above minimum wage. Union plants average $3.75 to $4 an hour for the same work, according to James Paris of the Food and Commercial Workers.

The union contract at Sanderson Farms started weak and stayed that way. There never was a well-developed grievance procedure. The international union did little to build the local.

The union came close to striking during the last contract negotiations, but they backed off partly because they feared they lacked the strength. Meanwhile, many drifted away from the union. The local won some grievances in arbitration, but others had to be dropped because it couldn't afford to fight them. By the fall of 1978 the union membership had dropped to 44 out of approximately 375 workers in the plant. The remaining union activists became convinced that Sanderson was systematically firing union people in an effort to eliminate the union altogether. Part of the union's problem stemmed from the high turnover: Sanderson had to hire 213 new people in 1978 to maintain his work force.

Recently, the international union— a roughly 85,000-member AFL-CIO affiliate based in Akron, Ohio—has shown signs of increased vigor and openness to leftist politics. In an attempt to strengthen the union's work in the South, special international representatives and new black organizers were sent in and older, white officials were shifted aside. Membership in the Laurel local climbed to around 200 shortly before the contract was due to expire on February 26, 1979. Little Joe had already offered the union a raise of 50 a cents an hour for extending the contract eighteen months. It wasn't a purely altruistic offer, since the minimum wage was scheduled to increase 45 cents by January 1981 in any case. Besides, as the strikers now insist adamantly, they were most concerned about the contract language, rules, and working conditions. Hubert Mills, then the international representative, urged the local to accept Sanderson's offer.

The local instead presented a long list of contract changes that would give them more power, starting with a revision a of the management-rights clause, which reserved exclusive power to management over virtually everything. They wanted a change in the absenteeism policy: workers only six minutes late for work had been counted as absent as far as discipline was concerned. Three absences within sixty days were grounds for firing. Anyone who refused overtime was counted as absent for the whole day. They wanted relief for toilet breaks as needed, fifteen-minute rest breaks guaranteed twice day, company-paid insurance, and more vacation. (Now workers get one week after year's work, two weeks maximum, but frequently they were told they couldn't take vacations because there were no relief workers.)

They wanted a strong seniority system. "Seniority don't mean nothing in there now," Jordan said. People are easily transferred or stuck with undesirable jobs regardless of seniority. Anyone off sick, without pay, had to start back with jobs from the "extra board" rather than in her old assignment.

They wanted a safer plant—guards in place on the saws, knives sharpened, freedom to go to the doctor when injured. They wanted to be able to negotiate the line speed, which Sanderson now can raise at will. The list went on and on, and they hadn't even spelled out pension and wage demands yet.

The union and company negotiators met three times before the deadline. The local even offered to extend the contract. But the company offered no response or counterproposal, claiming that the demands were so numerous and overwhelming that they didn't know where to start. "We had a union here for six years and we were never accused of anything like this," Sanderson, Jr., told me. "We really don't know what's going on." There was agreement to change the notorious rule allowing only three trips to the bathroom a week, but little else. The union's strike vote was overwhelmingly approved.

Then, the day before the contract expired, Little Joe pulled out his big guns. He called each shift into a meeting and ominously threatened that all strikers would be replaced immediately, starting with the better-paying "upgrade" jobs. Then he asked anyone who had questions to come into his office individually. The threat seemed to have cowed many of the second-shift workers, judging from the numbers who later crossed the picket line. But on the first shift, Magee stood up and asked Sanderson why people couldn't ask their questions in the group so everyone could hear the answers. Sanderson blew up, told Magee to sit down and shut up, and threatened to throw him in jail. Soon afterward, police were seen in the building.

"That was the most important speech he made," Magee said later. "The people said if he if threatens to put the president in jail, then we better go out."

The next day, three union leaders led out the day-shift strikers. The union estimates that roughly eighty workers refused to strike. Since then six strikers have returned, and Sanderson Farms has hired enough— many of them reportedly white—to run one shift. Negotiations continued but broke off in June. In May the National Labor Relations Board issued a complaint charging the company with bargaining in bad faith. More appeals and other delaying tactics can be expected as the company follows the advice of its law firm— Kullmann, Lang, Inman and Bee, one of the oldest, most established union-busters in the South. The company was also assessed a penalty for violating the child labor laws by hiring a 13-year-old strikebreaker.

In the spring of 1979 a petition was circulated to decertify the union. Circumstantial evidence suggests that the company was actively involved. Since there was already a charge of unfair labor practices, the vote can't proceed, but the company recently announced that it was no longer recognizing the union as a bargaining agent and gave its strike-breaking employees a raise of 20 cents an hour.

To gain greater leverage against Sanderson Farms, the International Chemical Workers (ICW) tried to organize the one Sanderson Farms plant without a union in Hazelhurst, Mississippi. (The plant in Louisiana has a Food and Commercial Workers local.) Robert Chinn, president of a Jackson ICW local and a civil rights movement veteran, was sent in to organize, and soon a small committee had union authorization cards signed by 130 of the 199 workers. But the onslaught from the company and its consultants was overwhelming. Workers were deluged in the plant with antiunion leaflets. If the union came in, they read, "You could lose some of your present benefits, your pay could be cut, your job could be eliminated, you could end up with less than you presently have. . . . Don't take a chance––vote to keep what you already have. Keep the union out of the plant.” There was another leaflet about four plants in Mississippi—"all four had unions—all four are now closed. . . .Vote for real job security. Vote NO!"' The specter of strikes––such as the one in Laurel––was raised repeatedly: "The plain truth is that while Chemical Workers Union members suffer on picket lines, often losing their homes, cars, and other possessions, the union bosses live high on the members' dues and fees money." In another leaflet, the union's way was described as "your way to work blocked by pickets––picket line violence, hate, and intimidation. . . . Part of your paycheck to be spent as the union sees fit. . . . Loss of freedom as an individual to handle your own affairs." And in a final reminder, a black worker speaks out on one leaflet titled "Don't Make a Mistake"': "I'm voting no union for my family and myself. I'm voting no dues, no strikes, no fines, no violence, NO UNION!"

The union organizing committee emphasized its commitment to needs expressed in a worker survey: wages, insurance, machine repair, determined that control of overtime, more vacations. But the company the workers' weak point was fear of a strike, and they hammered and held away on the theme. Management showed antiunion films and held propaganda meetings, excluding union committee members whenever possible. There were individual talks with employees. There was a promise of a raise of 50 cents an hour (which turned out to be only 20 cents). And there were the lightly veiled threats, such as the message rubber-stamped on the final paycheck before the balloting: "A Strike Will Stop This Check." The union lost 101 to 85, the third defeat at Hazelhurst.

Why, working under such conditions, do workers reject a union or cross a picket line? Chinn blames “harassment and the lack of knowledge about unionism" for the defeat. Many of the workers were poor country people who had never had another factory job. They were both grateful for what they had and scared of something that seemed unknown. “I think a lot of people are old and just don't know anything about a union,” organizing committee member Charlene Tanner said. "A lot of them grandmas just don't want to listen to what you have to say if you're young." But in Laurel many of the strikebreakers are the younger workers, new to the job and desperate for some money to support their babies.

Beulah Ramsey, 48, another Hazelhurst union backer with twenty years' experience in the factory, blamed ignorance and inexperience: "They're satisfied 'cause it's more money than they've ever made. They don't know what union is. Some can't even read or write. And some of 'em just love Little Joe. They'd just be clapping for Master Joe." The old deference of blacks to whites, of serfs to lords, and of women to men has not passed from the Mississippi scene, despite the victories of the civil rights movement. Many of the workers at the Sanderson Farms plants come from tiny towns and isolated rural homes, not even from larger towns like Laurel, with a population of around 23,000. Workers compare the New South industrial plants to the Old South plantations. "Little Joe always used the term, “These are my people,'” Jordan said. "That's a plantation phrase. He sincerely believes that."

"There are still a lot of people who believe the white man is supreme," says George Freeman, the international union director of community relations who has worked with the local since last fall.

"They say, 'I can't cross Master Joe. He been good to me. He gave me a job.' But the day comes when they can't produce and they'll be gone."

The plantation tradition shows up in the way the warp of sexuality weaves in with the woof of coercion to form a blanket of social control. Many of the mainly white male supervisors and foremen make sexual advances toward the younger women or those seen as more vulnerable, fostering loyalties to management and attempts to cater to the supervisors, workers charge. Many times, various women said, foremen would put their arms around them, caress them, or play up to them sexually as a way of countering resentment of discipline or of persuading workers to accept orders. “It's a big thing for some people in the plant for a white man to put his hands on them,” Jordan said. “They hug and pet on them and rub on them—and then they forget the grievance.”

Strikers repeatedly explained the behavior of the scabs as a result of deference, ignorance, and fear—of economic hardship, but also of the violence that has flared in the area. "There are people in there who believe whatever the boss tells them," Alice Musgrove complained as she sat on the picket line. "If he says the union is keeping them from getting a raise, they believe him.”

"Most people down here are kinda scared of unions," Magee explained. "They feel if you start organizing the man will fire you. Now people if they got a job feel it's the only one they can get. Most of the strikebreakers say they've got a car note, a color TV note. They also say you can't make Joe move, They felt they had to work, and they couldn't work anywhere else.”

Lack of education and lack of experience beyond their community also make many workers, especially women on their first job extremely unconfident. “Most of those people are illiterate,” Jordan said of the people crossing the picket line. “They don't know how to read and understand. You explain it all to them and they seem to get nervous, frightened, shaking like a leaf on a tree. It comes from not being able to understand, to read.”

Not all of the strikebreakers are hostile to the union, but some don't understand the importance of solidarity. "What they was doing was right and I knew it," Verlina Forthner, 21, a striker who returned to the job said about the union. “But the company kept hiring and I was afraid I'd lose my job. I thought the union demands was fair. I hope they win and get what they want. I think unions are okay, but don't see any sense in having a union in Mississippi because of the right-to-work law."

Although the union is charging Sanderson Farms with the unfair labor practices in the Hazelhurst election, it has temporarily lost that means of pressuring management. With the Laurel plant still operating as of the summer of 1979, the immediate hopes were that many of the strikebreakers were kids who would go back to school in the fall and cause new labor supply problems for Little Joe. They have also launched, with the support of the AFL-CIO, a national boycott of Miss Goldy brand chickens. And they have joined in sporadically with a makeshift local coalition of civil rights activists.

There hasn't been strong support from the black community, which has a long tradition of disunity and political bickering. Only a few ministers have publicly backed the strikers, leading to some bitterness. "My preacher said he ain't got no time," Grace Stevens, 37, said, "and I haven't been to services since. If the preachers had asked people to stay out of the plant, I believe they would have."

Critics of the labor leadership, such as Ken Lawrence, claim that the union efforts are really halfhearted: "I think it's partly because the majority of union members in the state are black and that poses a threat to the old guard of union leadership, which is white." Although some white union leaders, such as AFL-CIO state president Claude Ramsey, have supported the civil rights movement since the 1960s, many young black union activists and progressive politicians share Lawrence's sentiment, chiding the labor movement for timidity and lack of aggressive plans for organizing and for political influence. Many of these heirs of the civil rights traditions see such a revived labor movement as a leading mechanism for black progress. Some leaders, however, notably Charles Evers, the mayor of Fayette who sprang to prominence after the assassination of his brother Medgar, are antiunion.

Union leaders tend to blame antiunion consultants and the failure of labor law reform for many of their difficulties, but unions have managed nonetheless to establish themselves in all sections of Mississippi. In every major town the biggest industry is organized, presumably a solid point of departure for tackling the tough small shops.

The battle against Sanderson Farms will probably take more than victories in the courts and before the National Labor Relations Board—and even more than determination by the strikers—if the union is to win. It will take pressure from the community, from progressive forces around the state, and from the broader labor movement and its supporters. Already the strikers see their actions linked to others' lives. Alice Musgrove says, "Those places will say if Joe can get away working people the way he does, then why can't we?"

There is much to be overcome not only in the opposition from on high but also in the culture of those held down below. But struggles such as those at Laurel and Hazelhurst, the penetration of unions into the life of communities throughout the state, and the conviction of many blacks that their progress now lies with the labor movement all suggest that the future for the labor movement in Mississippi may not be as bleak as it now looks.

Ella Sheehan, 25, mother of two, a worker at Sanderson Farms for five years, has no regrets about her decision to strike— despite the hardship—and no hesitations about the value of a union: "I made up my mind,” she said. "I'm not going back in without a contract. It would be like slavery. I feel a lot different being out here from being up there treated like a dog. It makes me want to fight harder, even for my kids, because they'll have to work. It makes me feel good to have gone out on strike."

POSTSCRIPT, 1980: Fifteen months later, Sanderson Farms was still processing chickens, 65,000 per day instead of the usual 85,000 according to the company, on one shift instead of two. But the strikers were also gaining much-needed support, through the Committee for Justice in Mississippi, which counts the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the United Auto Workers, and the National Organization for Women among more than 150 endorsers. On May 17, 1980, 1,500 people with ICW president Frank Martino and SCLC president Joseph Lowery in the lead marched 5.6 miles through Laurel, chanting "We can't take it no more."

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.