Mississippi children's book project aims to close racial and gender literacy gaps

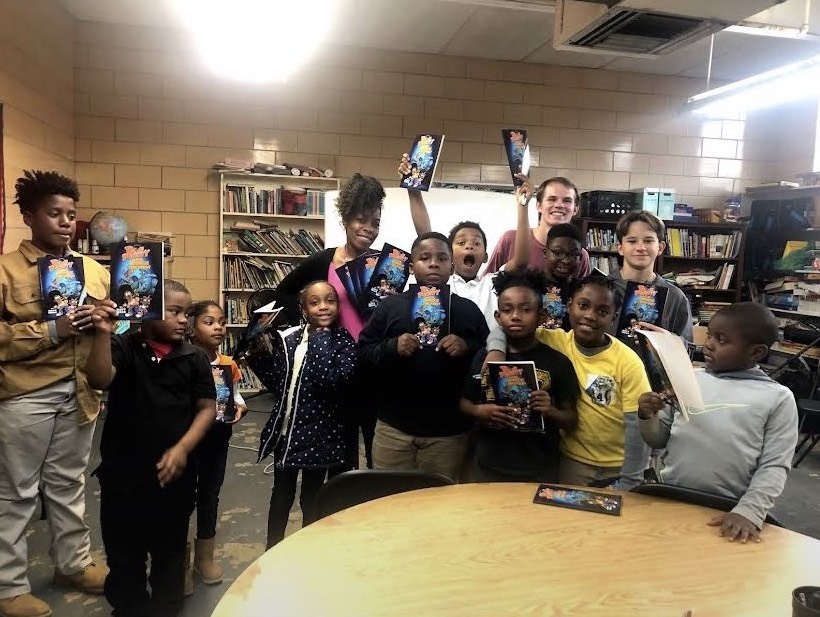

Children who attend after-school programs at the J.L. King Center in Starkville, Mississippi, are among those who have embraced Matt Maxx Books' "Big Monty" series, which aims to close racial and gender literacy gaps. (Photo courtesy of Matt Maxx Books.)

While hiking in Colorado's Rocky Mountain National Park in 2016, Alison Buehler and Jo Winn, former college roommates at the University of Southern Mississippi, started discussing the books that their kids enjoyed. When Winn, who is Black, shared that "Diary of a Wimpy Kid" and "Captain Underpants" got her children most interested in reading, Buehler, who is white, asked, "But what characters do they like who look like them?"

Winn had no answer. The two women immediately recognized a big problem: the lack of Black characters in children's books.

In 2018, the University of Wisconsin's Cooperative Children's Book Center found that only 10% of children's books featured Black characters — a lack of representation that contributes to the racial literacy gap. As of 2019, only 18% of fourth-grade Black students nationwide were considered "reading proficient," defined by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) as "demonstrated competency over challenging subject matter, including subject-matter knowledge, application of such knowledge to real world situations, and analytical skills appropriate to the subject matter." That compares to 45% of white fourth-graders. NAEP data shows the number is even lower for fourth-grade Black boys in Mississippi, at just 15%.

So Buehler and Winn, who are both writers, came up with a solution: write a funny book for young people featuring relatable Black characters. Over the course of several phone calls, Winn dictated a story as Buehler typed, creating Merlin Montgomery, a.k.a. "Big Monty," a middle-schooler who loves science, and his sister Josephine, whose adventures include saving their school from a monster made from lunchroom leftovers, a cyborg substitute teacher, and more. Several chapters end with easy-to-follow science lessons.

Matt Maxx Books was born. Told that there was a "lack of market" for Big Monty, Winn and Buehler turned to self-publishing.

"We knew we had a good story," Buehler says.

They chose the pen name Matt Maxx after their sons and created a "Where Are the Books That Look Like Me?" Kickstarter campaign. They organized the project under The Homestead Educational Center, a 501(c)(3) charitable nonprofit run by Buehler that raises money to "improve health, home, and community in Mississippi." The Kickstarter campaign collected $25,000 — enough to publish and distribute 1,000 copies of "Big Monty and the Lunatic Lunch Lady" and get started on the second book, "Big Monty and the Cyborg Substitute," which won a Mom's Choice Award. Both books were released in 2019.

The project went on to publish "Big Monty and the Pumped Up Principal" in 2020 and "Big Monty and the Malicious Music Teacher" this past March. The entire series has now sold and distributed more than 15,000 copies, selling as many as 900 books per month. School libraries have even reported waiting lists for students wanting to read the Big Monty books.

So much for the "lack of market."

Behind Big Monty

The Matt Maxx team has evolved since the release of the first book and now includes five people — writers, educators, and artists. Vanessa Shaffer, an educator, youth homeless advocate, and tennis coach in Starkville, Mississippi, has marketed and promoted the books from the outset.

"I was on board when I learned it was about the literacy gap for Black boys," says Shaffer, who is Black. "My children's doctors had emphasized how important it is to read to them, so I'd started before they were born. I wanted to help — whatever was needed."

Chris Miller, a Nashville-based artist who is also Black, has illustrated all four books. The initial Matt Maxx team contacted him in 2018 after seeing his artwork on Instagram. He provided draft illustrations for the first page and was hired immediately.

"The first book in the series was a bit harder," says Miller. "Once we hammered out a system, I'd get the script and a list of images they wanted on each page. Once I hit the basic markers, then I could embellish."

The current writer is Rudi Rudd, a Starkville-based educator with eight years of teaching experience in Memphis, where the books are set. "Because the target audience is grades two through six, it's important for the books to be linear," says Rudd, who is Black. "So I followed the same structure of the other books. For example, Big Monty introduces himself in each book so they don't have to be read in order. Something new we added to the fourth book is a switch in point of view from Big Monty to his little sister." Rudd also got help from a former colleague in Memphis with what she called "some of the more Memphis-inspired slang."

Buehler, who helped outline the first book, now focuses on publishing through the IngramSpark self-publishing platform and Amazon. While the fundraiser paid for the first book and the start of the second, sales through a local bookstore and online have funded the rest of the series. Buehler says sales have been highest in five cities: Atlanta, New York, Oakland, Chicago, and Dallas.

Beyond token representation

Shaffer initially promoted the books by speaking at schools and after-school programs like the J.L. King Center in Starkville, Mississippi, which focuses on educational and other programming for communities in need. Margaret Brown, the center's youth development coordinator, said that young people love the Big Monty books, and she has seen them make a difference.

"It has worked. It has helped," she said, pointing to an increased interest in reading and improved grades.

Miller and Rudd say it's important to them that the Big Monty series goes beyond token representation and presents Black children living happily. "There are books with Black kids that are good books but often contain a lot of tragic events," Rudd says. "It's not like that all the time. The Big Monty series shows kids being kids." She says it's also important to her that kids who aren't Black who read the book "get to see classmates who don't look like them doing normal things."

The books have changed the lives of the Matt Maxx team members. In the series' success, Rudd and Miller see encouragement for Black creatives — and the message that just because a major publisher isn't interested doesn't mean a concept isn't good.

"If you have an idea, don't wait," Miller says. "Put it down on paper."

Tags

John W. Bateman

John W. Bateman has a secret addiction to glitter and, contrary to his Southern roots, does NOT like sweet tea. His first novel, "Who Killed Buster Sparkle?" (Unsolicited Press) was a 2020 nominee in fiction by the Mississippi Institute of Arts & Letters and recipient of the 2019 Screencraft Cinematic Book Award. He recently left his Southern unicorn lumberjack shack in Mississippi and moved to Chicago to pursue an MFA in writing at SAIC. Learn more about John at www.johnwbateman.com.