Refusing to normalize voter suppression

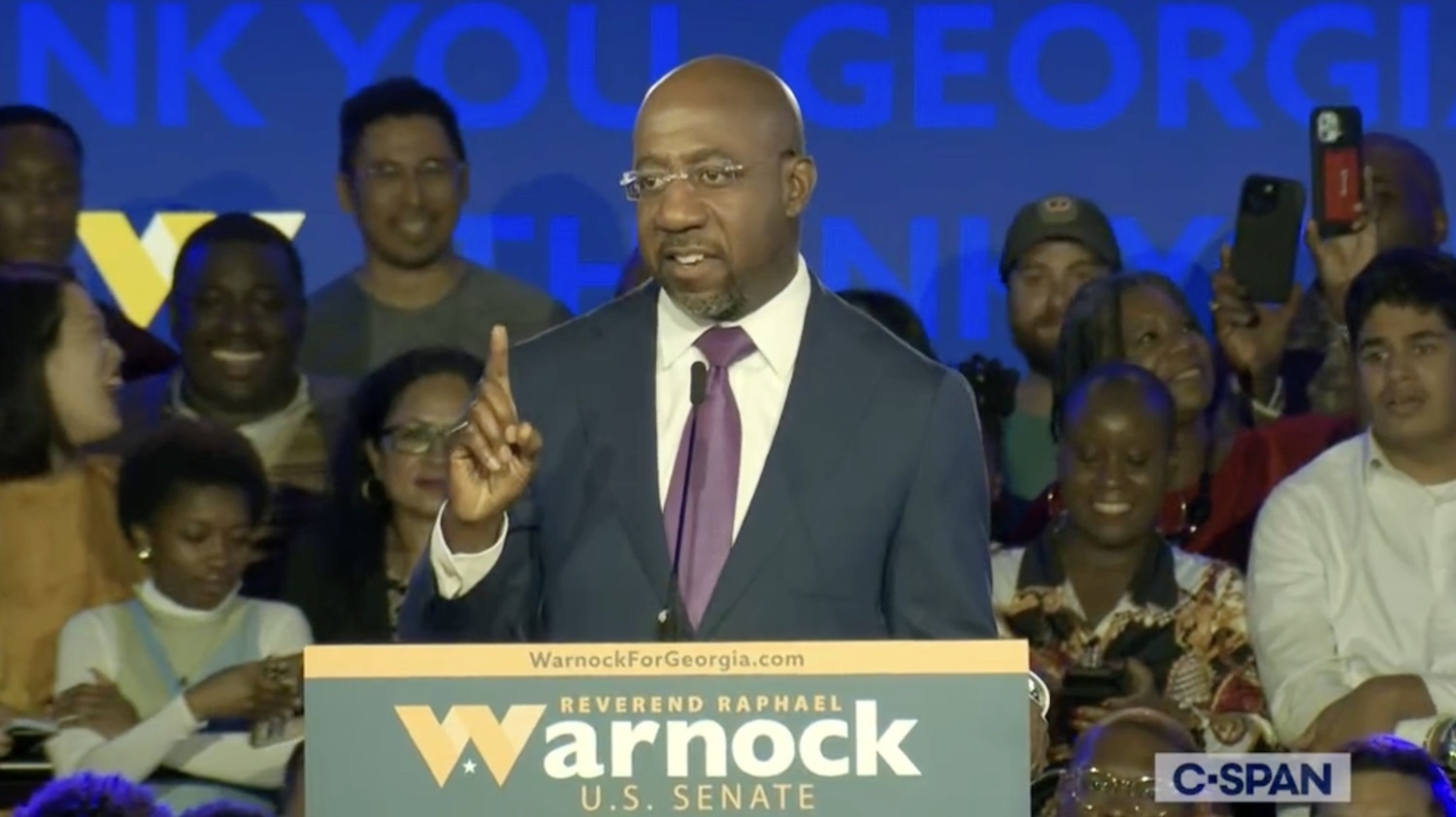

In his Dec. 6 victory speech, U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock of Georgia noted that the record turnout that led to his win does not mean that recent election laws aren't suppressing the vote. (Still from C-SPAN video.)

Earlier this month, incumbent Democratic U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock defeated Republican challenger Herschel Walker in the Georgia runoff election, strengthening the Democrats' control of the Senate. Historians note that Warnock — first seated following a special election that went to a runoff in January 2021 — became the first Georgia Democrat to win reelection to the Senate since Sam Nunn in 1990, and the first Deep South Democrat to win reelection to the institution since Louisiana's Mary Landrieu in 2008.

Warnock was elected amid record turnout for a midterm election in Georgia. But in his Dec. 6 victory speech, he refuted the idea that his victory means that voter suppression was not a factor in the race.

"Now there will be those both in our state, and across the country, who will point to our victory tonight and try to use it to argue there is no voter suppression in Georgia," Warnock said. "The fact that millions of Georgians endured hours in lines — and were willing to spend hours in line — lines that wrapped around buildings and went on for blocks, lines in the cold, lines in the rain, is most certainly not a sign voter suppression does not exist."

Georgia voters shattered midterm turnout records in 2022, in large part due to years of grassroots organizing by advocacy groups working in the state. Groups including Black Voters Matter led by LaTosha Brown and Cliff Albright, Fair Count led by Rebecca DeHart, Fair Fight led by Stacey Abrams, New Georgia Project led by Nsé Ufot, ProGeorgia led by Tamieka Atkins, and Women Engaged led by Malika Redmond played a major role in driving the record-setting turnout. Among the milestones achieved this year in Georgia, according to the secretary of state's office:

- All-time turnout records for a midterm election, with more votes cast than any other midterm;

- Record breaking midterm early voting turnout;

- Record breaking absentee-by-mail votes cast in a midterm;

- More Election Day votes cast in the 2022 runoff than on Election Day in the 2022 General Election, than on Election Day in the January 2021 runoff, or on the General Election Day in 2020; and

- Three days of single-day all-time voting records during early voting.

But Georgia Republicans sought to counter growing turnout. For example, they tried to prohibit voters from casting a ballot on the Saturday before the Dec. 6 runoff because of a 2016 law that prohibits early voting on the second Saturday during the runoff if there's a state holiday preceding it. In this instance, Thanksgiving is on Nov. 24, and a holiday created to observe Confederate General Robert E. Lee's birthday is on Nov. 25. Warnock sued over the policy, along with the Georgia Democratic Party and the Democrats' Senate campaign arm. The Democrats prevailed, allowing counties to offer early voting on the Saturday in question.

But other policies that restricted voting remained in place. Many of them were put there by a controversial 2021 Georgia law that among other things ended voters' ability to present an absentee ballot request completely online by requiring a pen and ink signature, restricted access to absentee ballot drop boxes, and shrunk the window during which absentee ballots can be requested and submitted. The law also cut in half the time allotted for the runoff election.

Georgia wasn't the only place where voters grappled with policies and practices that made it harder for them to cast ballots. Voting rights advocates nationwide documented thousands of voter complaints throughout the midterm election cycle. They included long lines, malfunctioning machines, delayed poll site openings, intimidation, threats, and misinformation. The majority of harassment, misinformation, and intimidation allegations came from voters of color, prompting fears that there were systematic efforts to suppress their turnout in 2022.

These concerns were especially prevalent in Southern states, where increasingly diverse populations are ruled by Republicans who support restrictive voting laws. Volunteers with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund Voting Rights Defender Project who monitored polls in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas reported nearly 1,000 incidents throughout Election Day. These included shortages of paper ballots, problems with accessibility and identifying polling locations, voter intimidation, poll worker misconduct, and voters not receiving requested absentee ballots.

Voting rights experts note that voter suppression does not always manifest as outright denial, but can be revealed in more subtle ways that can still have a devastating impact on marginalized communities. For example, a 2020 analysis by Stanford University political science professor Jonathan Rodden of data collected by Georgia Public Broadcasting and ProPublica found that the average wait time after 7 p.m. across Georgia during the June primary was only 6 minutes in polling places that were 90% white but 51 minutes in polling places that were 90% or more nonwhite. And in this year's U.S. Senate runoff, wait times in the Atlanta area during early in-person voting were more than two hours.

"It's death by a thousand cuts," Kendra Cotton, CEO of the voting rights group New Georgia Project Action Fund, told CNN. "They are not trying to hit the jugular, so you bleed out at once. It's these little nicks, so you slowly become anemic before you pass out."

'In a precarious position'

Voting rights advocates argue that long lines are discriminatory, suppressive, and a direct result of the U.S. Supreme Court's evisceration of the Voting Rights Act in its 2013 decision in the Shelby County v. Holder case out of Alabama, which effectively ended federal preclearance for election changes in jurisdictions with a history of voter discrimination. This allowed Republican-controlled state legislatures to implement restrictive voter ID laws, shrink early voting periods, and eliminate some voting locations, all of which disproportionately affect Black voters and other marginalized communities.

Meanwhile, Republican-led efforts to directly restrict voting have ramped up across the country. The Brennan Center for Justice tracked over 400 restrictive voting bills proposed at the state level this year. For instance, Republicans lawmakers in Texas are preparing to advance a series of changes to the state's voting policies, including a proposal to create an election police force like the one Florida controversially established before the 2022 midterms. Advocates say that these measures would directly target communities of color, leading to a surge in intimidation and voter suppression.

The Supreme Court is now considering another case that could have far-reaching impacts on elections. The Moore v. Harper case out of North Carolina hinges on the controversial independent state legislature theory, which holds that only state legislatures — not state courts, governors, or other bodies with legislative power, like independent redistricting commissions — should control federal elections. If the majority of the court embraces it, the precedent would further limit challenges to discriminatory election laws. "This could be the final nail in the concept of democracy in this country, if these state legislatures are able to run rogue without having any kind of accountability," Albright of Black Voters Matter recently told Democracy Now.

To date, congressional Democrats have been unsuccessful in passing federal legislation aimed at shoring up voting rights, including the Freedom to Vote Act and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act. But with Republicans set to take control of the House next month, some Democrats have not given up trying. Most recently, members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) sought to include the bill named for Lewis in an $858 billion measure to fund the Defense Department, but they were stymied by the House leadership.

"It seems like the Black caucus has always supported leadership in what it's tried to do, but leadership of this caucus hasn't returned the favor, always," said CBC member Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.), adding, "And so now we're in a precarious position where voting rights will continue to be under attack — state to state — will continue to be gutted."

But voting rights advocates say they will continue to pressure federal lawmakers to pass reforms to make the voting process freer, fairer, and more accessible. They're already looking to the next presidential election and calling on federal lawmakers to develop a strategic plan to pass federal voting protections before then.

"All who believe in the freedom to vote, including the president and members of Congress, must start creating a roadmap for 2024 now," Albright and Brown of Black Voters Matter said in a statement. "Voter suppression — in all of its forms — cannot become normalized."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.