The South's union membership stagnates, but workplace protests grow

Last January, activists in Philadelphia marked the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday by picketing in solidarity with workers who are organizing at Amazon, Starbucks, and other companies in the South and elsewhere. (Photo by Joe Piette via Flickr.)

While support for labor unions in the United States is at its highest level in more than five decades, the percent of workers belonging to unions declined nationally in 2022 and flatlined in the South.

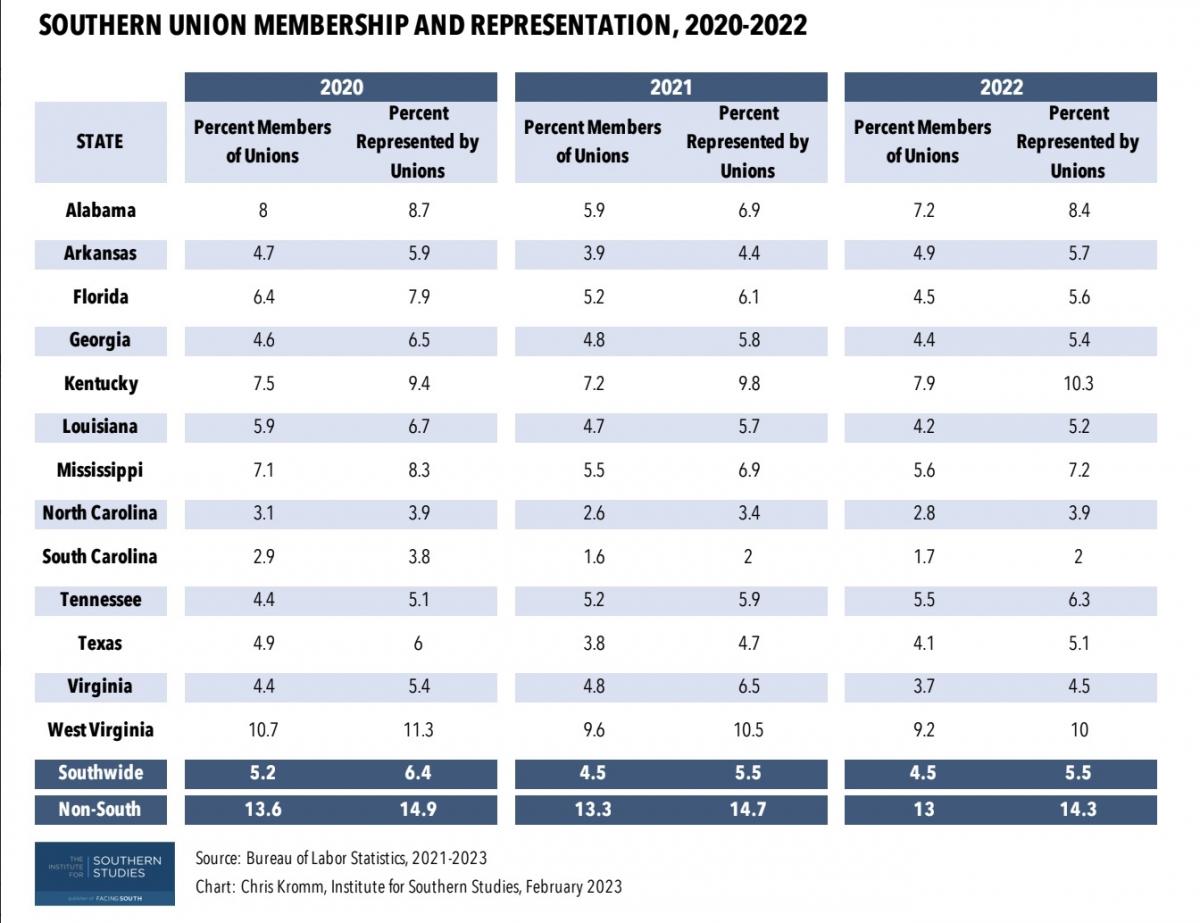

Data released last month by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) found that the share of workers belonging to a union nationally dipped slightly from 13.3% in 2021 to 13% last year, and that unionization in the South held steady at 4.5% — more than 8 percentage points below the non-South average.

While some Southern states saw union density gains — most notably Alabama, where the percent of workers in unions jumped from 5.9 to 7.2 — those were offset by declines in Virginia, Florida, Louisiana, and other states in the region.

The South's lagging unionization rates — and the challenges its workers face organizing unions due to political and corporate opposition — aren't new. But the current lack of union growth comes against a backdrop that includes heightened public sympathy for unions, a tightening labor market that gave rise to "the Great Refusal" and boosted workers' negotiating power, and a series of high-publicity organizing advances at Amazon, Starbucks, and other workplaces.

Labor leaders explain this apparent disconnect by pointing to the immense structural barriers to union organizing — especially in Southern states, where so-called "right-to-work" laws allow employees to enjoy the benefits of a union contract without having to join the union, and where a pro-business political atmosphere on both sides of the aisle means corporations rarely face meaningful consequences for using heavy-handed tactics to defeat union drives.

"[2022] was a year of real worker power, due to huge job openings," as Heidi Shierholz, president of the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), told The Washington Post. "The question will be whether that comes out on top compared to the very, very strong downward pressure on unionization because of employer opposition."

Growing interest and activism

All signs point to rising interest in unions and greater labor activism over the last year, both nationally and in the South.

Last year alone, there were more than 900 strikes and other labor protests across the country, according to a database maintained by the New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University. Of those labor actions, 150 took place in Southern states — a 22% increase over the previous year.

The industry experiencing the most labor disruptions in the South, with more than 40 last year alone, was accommodation and food services, which faced widely publicized organizing drives at Starbucks. Schools and educational institutions saw more than 20 labor actions in the region, as did the transportation sector, led by airline employees represented by the Communications Workers of America.

In another measure of union interest, the number of petitions for union representation jumped 54% nationally in 2022, according to the National Labor Relations Board.

Public support for unions is especially high among younger workers. For example, a recent survey by the Center for American Progress (CAP) found that a majority of all generations have favorable views of unions, but Gen Zers — those 26 or younger — show the highest approval rating by far, at 64.3%.

"Young workers are not only more supportive of unions than older workers today," observed the CAP survey authors, "but also more supportive of unions than older generations were at their age."

Struggling to make headway

The growing interest in unions in the South and country did show up in the BLS data: Nationally, the number of workers in unions grew by 273,000 between 2021 and 2022. In Southern states, their number increased by 83,000.

But the percentage of workers in unions declined nationally — or, in the South's case, stagnated — because non-unionized businesses added even more workers in 2022 as companies emerged from the COVID pandemic. (Click on the chart for a larger version.)

Alabama, Kentucky, and West Virginia remained the South's most unionized states, although union density has fallen in all three over the last decade as manufacturing and mining jobs have declined. Florida and Mississippi, which used to be among the South's most unionized, have seen a sharp falloff in membership: from 6.4% of Florida workers in 2020 to 4.5% last year, and from 7.1% of Mississippi workers in 2020 to 5.6% last year.

While the gender gap in union membership is now small, there are pronounced racial disparities. EPI has found that Black workers have the highest unionization rates, at 12.8%, in part due to pro-union attitudes among Black workers, and also because of the high rate of unionization in public sector jobs, which are disproportionately held by African Americans. That compares with 11.2% for white workers, 10% for Latinx workers, and 9.2% for Asian American and Pacific Islander workers.

Labor advocates believe that burgeoning pro-union sentiment and growth of new organizing efforts at Amazon, Starbucks, and elsewhere in the South will eventually translate into higher union membership, but the barriers are formidable.

While corporations benefit from "right-to-work" statutes and other laws that limit unions, they also use illegal efforts to stop labor organizing: According to National Labor Relations Board data for union elections between 2019 and 2022, employers were charged with violating federal labor law almost 40% of the time, using tactics ranging from retaliatory firing to changing work terms. In addition, corporations spend heavily to block unions. A 2019 study found they spend more than $340 million a year on "union avoidance" consultants to defeat labor organizing drives, a number that has likely risen alongside union elections.

"In 2022, we saw working people rising up despite often illegal opposition from companies that would rather pay union-busting firms millions than give workers a seat at the table," Liz Shuler, president of the AFL-CIO, said in a statement on the latest BLS data. "The wave of organizing will continue to gather steam in 2023 and beyond despite broken labor laws that rig the system against workers."

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.