From the Archives: Michael Simmons on the economics of the Great Migration

(Olivia Paschal / Southern Exposure)

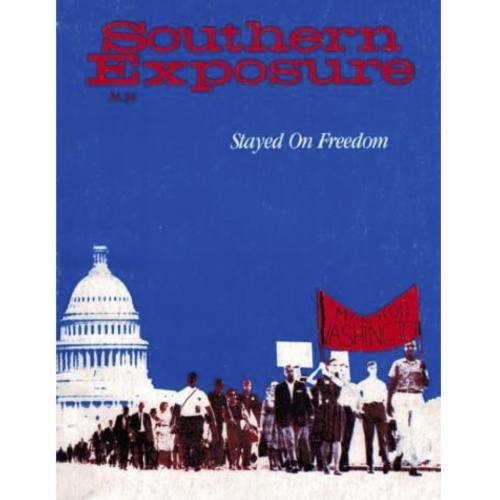

Michael Simmons has been a longtime Black organizer working across regions and movements, from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Arkansas to SNCC’s Atlanta Project and workers' organizations in Seattle and the South. As Ajamu Dillahunt writes in a review of "Stayed on Freedom," Dan Berger's new book about Michael's and his ex-wife Zoharah Simmons' involvement in freedom struggles, the Simmonses' lifetime of work "demonstrates determination and considerable discipline."

In 1975, as Michael Simmons was organizing workers' groups in the South, he was also writing for Southern Exposure. In the magazine's 1975 issue "Southern Black Utterances Today," co-edited by Toni Cade Bambara and Leah Wise, Simmons reviewed "Black Migration," a book by Florette Henri about the economics of the second Great Migration, when millions of Black Southerners moved North in search of better schools, better jobs, and to escape Jim Crow laws.

The review is a nuanced piece of writing that takes Henri's history seriously for the lessons it imparts, but also criticizes some of Simmons' fellow travelers in labor and anti-racist movements for their unwillingness to indict the system. "Black unions made the same mistake as white unions," he writes. "In accepting the basic economic tenets of American capitalism, they were merely jockeying for more of the economic pie … the enemy became one's fellow worker, not the employer — which explains why attacks made on the employer seldom got beyond a bid for higher wages and benefits to a demand for worker control of plants, including what a plant produces."

We republish Simmons’ full review here.

While growing up in Philadelphia with parents from South Carolina and Georgia, I always assumed that Blacks in the Southeast migrated to Philadelphia. Years later, as a young adult working with SNCC in the Deep South, I was surprised to find Black Southerners talking about moving to places like Cleveland, Gary and Chicago, and I was amazed at the number of Black Northerners my age who, like myself, were only one generation removed from the South. For the first time, I realized the scope of the twentieth-century Black migration.

In the last few years, another organizing experience in the South has led me to think again about migration patterns in the context of our struggle. I was involved with a workers' group in Seattle, Washington, which wanted to extend its organizing efforts into four central southern states, but which recognized the cautious reactions of the people there towards "outsiders." We suspected that many Blacks in Seattle had migrated from the four-state area, so we shared our proposed project with various church congregations in order to get names of their southern friends and relatives. From these names, we located the initial contacts who proved indispensable in establishing our immediate legitimacy in new communities.

That experience brought me to Black Migration by Florette Henri (Doubleday, 1975). Ms. Henri is less interested in tracing the actual geographic patterns of the dispersal than in analyzing the accommodation experience of Blacks who migrated North in search of improved employment opportunities, better schools and an end to discrimination. Nevertheless, her treatment of this important transition during 1900-1920 is instructive, particularly at a time when we are attempting to understand our history in order to plan for the future.

A boy is born in hard time Mississippi

Surrounded by four walls that ain't so pretty

His parents give him love and affection

To keep him strong, moving in the right direction

Living just enough, just enough for the city....

Ms. Henri prefaces her main discussion with a brief account of the "Reconstruction." The experience of Blacks demonstrated that the Civil War had less to do with slavery as a question of equality than with a struggle between the economic interests of the North and the South. The 1877 Compromise was the beginning of that realization for Blacks, although it took nearly 25 years to completely reestablish white supremacy in the South. During this period Blacks witnessed the emergence of laws that restricted their participation in society, the establishment of a modified form of slavery known as sharecropping, and the rise of white terrorist groups dedicated to the suppression of Blacks. These events, culminating with Plessey v. Ferguson, left southern Blacks in 1900 with only the psychological benefits of emancipation.

The first two decades of this century were significant for America. Having consolidated a reunified state apparatus following the Civil War, America was geared toward further expansion. The subjugation of the Native American population had been completed and the military conquest of Mexican land achieved. Still America continued looking beyond its borders to increase the economic growth of the country. Thus, by 1910, the national wealth had doubled and by 1914 American investments abroad had increased five times their 1897 level.

His father works some days for fourteen hours,

And you bet he barely makes a dollar.

His mother goes to scrub the floors for many

And you best believe she hardly gets a penny.

Living just enough, just enough for the city....

The technological age had arrived and along with it came the need for labor. While many people are familiar with the methods American businesses utilized to entice Europeans to immigrate, few realize that similar tactics were used to induce southern Blacks to migrate north. Ms. Henri describes how companies sent agents throughout the South, encouraging Blacks to travel north to cash in on the guarantee of jobs, good housing, better schools and “equal opportunity." The South became so alarmed at the loss of its neo-slave populace that states passed laws to curb the activities of these agents. Many Blacks also contributed to the rise of the exodus fever, the most notable being Robert Abbott, editor of the Chicago Defender. Through his newspaper, Abbott acted as the unofficial organ of northern business, extolling the opportunities of the North and the need for Blacks to abandon the oppressive South.

His patience's long, but soon he won't have any

To find a job is tike a haystack needle

Cause where he lives they don't use colored people.

Living just enough, just enough for the city....

Newly arriving Blacks soon realized that, as Malcolm X once noted, they had arrived "up South." They found they "could always get some dirty, exhausting, low-paid work." In the plants, 90 percent of the Black industrial workers were common laborers; in the Chicago stockyards, the highest position a Black could obtain was subforeman of other Black workers, and that was an unusual occurrence. The European immigrants that arrived in America from 1900-1920 were not of "sturdy stock .like Europeans from northern Europe," as Woodrow Wilson pointed out, but were often darker-skinned people from central, southern and eastern Europe who experienced discrimination similar to Blacks. Being placed on the same economic level as Blacks resulted in the new immigrants competing for the "negro jobs." Ms. Henri observes that "Italians, Sicilians, Greeks by 1910 were replacing Black barbers, bootblacks and drymen . . . ."

The lack of an economic analysis by both Black and European immigrants pitted the two groups against each other while big business picked and chose from the overabundant labor supply filling the cities. Black folk made the mistake of assuming that, because we were here first, we had some form of squatters rights over the newly arriving immigrants. Ms. Henri is correct in noting the tragedy of Black leaders who exhibited the same racist attitudes of the conservative nativist movement, accusing the foreigners of being disturbers of the peace and socialist agitators. Equally tragic was the racist attitude of the new immigrants who saw Black people as blocking them from carving their niche in America.

In the trade union movement this conflict between Black and immigrant labor intensified. Although the history of labor unions in this country cannot easily be characterized by a general statement, or a broadly racist label, race did play a prominent, negative role in the formation of unions. Black people often found that they were viewed "problematically.” Black workers were restricted from joining unions and often were used as scabs during union struggle. Ms. Henri states that Blacks were members of some unions, such as the United Mine Workers, Teamsters and Longshoremen, in areas with large Black work forces, where the unions had to include them or lose control over employees.

Unions, such as the Amalgamated Association of Steelworkers, the Hotel Employees and the Tobacco Workers, that refused membership to Blacks organized separate "lodges" which were under the jurisdiction of the nearest white local. Black unions formed in a number of trades with A. Philip Randolph's Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters being the most successful.

But Black unions made the same mistake as white unions. In accepting the basic economic tenets of American capitalism, they were merely jockeying for more of the economic pie. Rather than struggling for a just economic system that could provide for all, they defined their struggle as a battle over crumbs in an economic system that is premised on the exploitation of workers. Thus, the enemy became one's fellow worker, not the employer— which explains why attacks made on the employer seldom got beyond a bid for higher wages and benefits to a demand for worker control of plants, including what a plant produces.

His hair is long, his feet are hard and gritty

He spends his life walking the streets of New York City.

He's almost dead from breathing in air pollution.

He tried to vote, but to him there's no solution.

Living just enough, just enough for the city....

Throughout Black Migration Ms. Henri documents the history of Black people attempting to participate in American society as equals. Her chapter on the Black experience in World War I gives a vivid picture of the extent to which we were willing to compromise basic humanitarian principles toward this end. I found it difficult to sympathize with my brothers who were so willing to be used as cannon fodder as a down-payment on equality. This attitude was and is responsible for Blacks being used to take the land from Native Americans and Chicanos (the Buffalo Soldiers), as well as from other Third World peoples (the Philipines, Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico, Korea and Vietnam). Domestically, we were proud to accept any high-level post regardless of task. For example, one of the "good negro jobs" during this period was Assistant Attorney General for Indian Affairs. Imagine us administrating the colonized for the colonizer!

Unfortunately, Ms. Henri never considers the possibility that Blacks were operating out of an incorrect framework. Instead, her book demonstrates how Black people defined the goals of freedom and opportunity in terms of the material benefits that dominate white society. Blacks failed to question how America's standard of living was achieved and how the subjugation and exploitation of peoples around the world provided it. Various movements, such as the Harlem Renaissance, exhibited a changing sense of how to take advantage of opportunities, but few questioned the nature of American opportunity itself.

As we look at history, however, we must always recognize that there are varied currents operating simultaneously within the mainstream. We need to know more to develop a complete understanding of those voices that did challenge American society and its operating principles. Nevertheless, Ms. Henri's account shows masses of Black people struggling through horrendous circumstances to advance themselves and their families the best they knew how. For this we have nothing to be ashamed of. But today we know better. As we have watched the bombings of the Vietnamese people over the past 15 years, the insidious American-sponsored coup in Chile, and the continual exploitation of Blacks and other Third World peoples, we can never again fight for our equality in ignorance. For achieving our own separate peace is merely the tacit acceptance of the exploitation of others. If our struggle is to win against exploitation, it must be joined with struggles of oppressed people everywhere.

I hope you hear inside my voice of sorrow

And that it motivates you to make a better tomorrow.

This place is cruel, no where could be much colder

If we don't change, the world will soon be over.

Living just enough, stop giving just enough for the city!!!

"Living for the City" by Stevie Wonder, from the album Innervisions © Motown Records, Inc., 1973.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.