Why We Did What We Did: Reflections from Sue Thrasher, Leah Wise, and Bob Hall

From left to right, Chip Hughes, Leah Wise, Sue Thrasher, and Bob Hall during a panel at the Southern Exposure at 50 event at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill's Wilson Library in March 2023. (Photo by Olivia Paschal)

In March of this year, at Pages from the Movements for Justice: Southern Exposure at 50, a panel of some of the Institute’s early staffers—Sue Thrasher, Leah Wise, and Bob Hall—reflected on the founding of the Institute for Southern Studies, Southern Exposure, and the movements and networks for change that we have been embedded in, part of, and helped to create over the last fifty-plus years. In partnership with the Southern Labor Studies Association’s Working History podcast, we have published the audio of the panel as a podcast. You can listen to the full panel here, and read a transcript below. (We also published an edited version of Sue Thrasher’s comments just after the event.)

Olivia Paschal: This is series co-host Olivia Paschal. Today I'm excited to bring you a special episode of Working History, in partnership with the Institute for Southern Studies. This week's episode features a panel recorded live at the 50th anniversary celebration of Southern Exposure magazine, which was held in March at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Wilson Library. The Institute for Southern Studies and Southern Exposure magazine will be familiar to many of you as stalwarts of Southern movements for justice since their founding in the 1970s. This panel, titled "Why We Did What We Did," reflects on the founding of the Institute and the creation of Southern Exposure. It features three of the key figures in the Institute's and Southern Exposure's founding: Sue Thrasher, a co-founder of the Institute, who later worked at the Highlander Center; Leah Wise, one of the Institute's early staff members and later the director of Southerners for Economic Justice; and Bob Hall, the founding editor of Southern Exposure, who spent many years at the Institute for Southern Studies and was later the longtime executive director of Democracy North Carolina. It is moderated by Chip Hughes, an early Institute staffer himself, and an occupational health and safety organizer before a long government career in public health.

I myself worked at the Institute for Southern Studies full time as a journalist at its online magazine, Facing South before graduate school, and I stuck around while in grad school to work on a multi-year project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive. The magazine contains a wealth of material on oral history, the Southern labor, civil rights, economic justice, and women's movements, and the South writ large through the 20th century. You can find a link to the digital archive, which is constantly being updated, in the show notes. Many thanks to Emanuel Gomez-Gonzalez for capturing video and audio of this panel session, and to the many people at UNC and at the Institute for Southern Studies whose work made the event possible.

[panel recording begins]

Benjamin Barber: My name is Benjamin Barber. I'm the Democracy Program coordinator for the Institute for Southern Studies. We just want to welcome you to this fiftieth anniversary of Southern Exposure. Thank you all for joining us at this event and diving into this history with us. You know, there's a quote that I think speaks to the purpose of this event, says so much about the history that we are talking about. It simply says "the struggle of humanity against the oppressive power is really the struggle between memory and forgetting." And all of us here recognize that the history of the South is a history of struggle and solidarity. And that is something we can never forget. So today, we hope to have some powerful discussions about this issue, the importance of preserving this issue, but not only preserving it, but actually using it to make history. We are honored to have you all with us. And I'm going to pass it to Olivia just to give some additional information on the archives and other logistics.

OP: I'm Olivia Paschal. I am the archives editor for the Institute for Southern Studies and Southern Exposure. I used to be a journalist for Facing South, but I'm also a grad student in history. So this has been just a really wonderful event to hear from you all throughout today and get to meet many of you whose bylines I've seen in the magazine as I've been working with it. I just wanted to make a quick plug for those of you who are on Zoom, and those of you in person, for the new Southern Exposure digital archive, which is live as of two or three days ago. And so I hope that you all will visit it, make use of it. Use it for students, send it to classrooms, we really want it to be a resource for folks who are researchers, who are students, who are organizers. The URL for that is facing south.org/southern-exposure. So please check that out. And it looks like all of our panelists are here, so we will hand it on over to Chip.

Chip Hughes: Yeah, I mean, first I want to give thanks to my two partners that you just heard from. The three of us sort of came together last summer and started talking about this idea of intergenerational conversation. And I feel like given the audience that we have here in the room and on Zoom, I feel like we've really been successful as organizers in bringing together a really great group of people, both veteran and newbie and aspirational. And thanks to all of you guys, for doing that.

Within the proud history of Southern Exposure magazine and the Institute for Southern Studies, is a great appreciation for the power of social movements. Learning from the grassroots, preserving the history of disenfranchised groups, creating avenues for participation in social and political change, have always been the core parts of the mission of SE and ISS. In our founders panel, we will begin with reflections from each of our panelists and then move to facilitating a dialogue with all of you, virtually and in the room.

To begin with, I'd like to paraphrase from one of my friend Bob's immortal memos [laughter] which attempt to describe who we are, what we did, and why we did it. "As the staff of Southern Exposure, we don't represent one politically correct line. We are aimed to continually discuss and learn new ways to organize our lives, to support the movements for social justice, and understand the larger oppressive forces at work in the world and in the South. Broadly speaking, we were, and I think we are, anti-capitalist, anti-racist, populist-oriented in perspective, and united in our understanding that we don't have all the answers, but we agree on getting a story, getting to the truth, and building a way to stand up for civil rights and social justice."

As Bob said, "It is a dialectic in the sense that we foster a conversation between the arc of history and the present moment. We listen to the voices at the grassroots routinely. They are often ignored by the mainstream press, and by those who write history. Our organizing and advocacy focus is on changing the lives and conditions of oppressed people, and fighting the powers that are attempting to manipulate them and dominate them politically and economically." So to begin, we will hear from Sue Thrasher, Leah Wise, and Bob Hall.

And I'll just sort of read the questions that we started with in our discussion about doing this panel, which is: How would you describe your personal and historical roots that Southern Exposure and the Institute for Southern Studies grew out of? How did starting the magazine relate to the larger Institute goals for supporting the social movements, creating a sustainable organization, creating an outlet for investigative journalism, and exploring alternative culture and history? Could you describe a couple of examples of how each issue theme grew out of a social movement, previously neglected stories, and other areas that were ripe for investigation? What contribution do you feel Southern Exposure has made to keeping alive ongoing social justice movements in the South, as well as investigative journalism, social action research, and grassroots storytelling? And lastly, how is the work and legacy of Southern Exposure and the Institute relevant to today's movements for social justice, and keeping alive the telling of disfranchised people's history in the region?

Sue Thrasher: I just want to start by thanking Chris and all other people who put this event together. It is really wonderful to be here and really wonderful to celebrate this anniversary. And clearly a lot of work has gone into this event, so thank you very much.

The first question, Chip, asked us was about roots, and I'd like to start as far back as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. And that's about the personal, personal thing for me in terms of my own involvement, but it also was very much a part of that early Institute for Southern Studies.

There were three people involved in conversations in the beginning about forming an institute. One was Julian Bond, who was at that time the communications director of SNCC, Howard Romaine, and myself. The first meeting that I remember was actually on a porch on Raymond Street in Atlanta at one of the old SNCC offices, where we sat outside and talked about the work that Jack Minnis was doing inside SNCC, which was corporate research, power structure research, and how we could, what the movement needed to sustain itself over a period of time and what kind of information might be needed and whether or not we could look at that and build something from that.

That was one of the early conversations and those conversations continued for several years. That conversation must have taken place as early as 1966 or even earlier. Eventually, I went off to the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C., which is another key part of our history. I was on my way to the New School for Social Research to go to graduate school. But I never went to the new school because I thought the Institute for Policy Studies is really the graduate school that I wanted to be at.

About a year later, I was asked to become the administrative fellow at the Institute and the deal I made with them is that we would be able to work on creating a Southern Institute over the next few years, and that they would support that work, which they agreed to do. So over that period of time, Howard would occasionally come to D.C., Julian would be in and out of D.C., and we'd have ongoing conversations about creating a southern Institute.

When I go back and think about why we did what we did, you know, the easy, the quick answer to that is that we wanted to sustain the movement, we wanted to build the movement, to grow the movement, and to make sure that people had what they needed, the kind of information they needed to remain active. Now, between the early conversations and the 60s, and the time we started in 1970, the movement, the mass movement had really shifted in many ways by that time, and was much more was more, not so much a mass movement, but much more multiple movements, organizations, people beginning to come out of activism in the Vietnam War, beginning to get involved in environmental issues, beginning to look at corporations, much more a broader movement as such an and harder to identify as the kind of earlier mass movement civil rights movement that we had really came out of, and were talking about.

So I think when we started the Institute for Southern and began thinking about what we were going to do to grow this movement, we had to recognize that shift. And we were sort of making that road by walking it in terms of trying to respond to what was going on. And eventually, Southern Exposure came out of our conversations as a way to get out the work that we were doing.

But if you look at the first three years, excuse me, the first three issues of Southern Exposure, they represent what, two or three years of work at the Institute prior to that time. So the work on the study, Howard Romain had talked endlessly about the defense industry in the South and Richard Russell, and how we had to document that the Georgia Power Project, and Atlanta was key to the work we did in the second issue that came out. And then Leah, and myself ,and Jacquelyn Hall had started doing oral history work by this time, and I guess you asked to talk about a particular issue.

So I'm gonna talk specifically about No More Moanin' here. Anne Braden was a mentor for me, and she at one point had said to me, "You really don't know your history, you really think that you're," she said, "you're really sort of arrogant," and not me—she was talking about all of us. But she certainly meant me as well. She was saying that all of us, you really need to discover your own history. And you need to know about the people who were active in the 1930s and 40s, because people have done this before. You think you're the first, but you're not the first. So go find out your own history. Well, to find out — that history was not written in the books. So you really had to go find new ways of doing it.

And so in conversations with Jacquelyn and Leah, and I don't know whether you, Bob, and probably Bob was involved in those conversations as well. But we developed an oral history project. The Institute had very little money, and the three of us have talked about this, especially over the last few weeks. How did we do what we did? And to tell you the truth, we don't know. We just got money, little pieces of money, here and there. But we did do a whole series of interviews on the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Leah went to Arkansas — I went to Arkansas on a trip to interview J. R. Butler, Leah went back to Elaine, Arkansas and found people who have been involved in the Elaine Massacre. We began interviewing people who had been involved in the early labor movement. We did the interviews with the UAW sit-down strike people in Atlanta. And just we began interviewing who we could and when we could on a shoestring and that eventually became the third issue of Southern Exposure. It was the first double issue because we had, I think I refused to take anything out. Also, it was because we were behind and we needed a double issue. Bob insisted that we make it the rest of the year. So we did Southern Exposure based on that.

The other thing I want to say is that I think what was important about the founding of the Institute is our belief that we could create our own institutions and sustain them. And that then we could manage them, we would have the freedom then to do the kind of work that we knew had to be done. And we didn't feel that we could do that in the organizations and the institutions that were already there, so the only real alternative was to create and try to make possible our own institutions. And I think back about that, and it's, it's, I mean, talk about, if Anne Braden thought I was arrogant about history, creating an institution like that and thinking you can sustain it over time, that takes real, something or other to do that.

And all of you in this room who worked on Southern Exposure, and I'm sure those people who are staff, people now know exactly how you did that. You did it through incredible long working hours, you did it through commitment, and you did it by scrounging, because that's the way we keep those institutions alive. So that's the early part of what we did. I think in terms of Southern Exposure, there's just — Bob, Bob, led us to Southern Exposure by saying we need to, we need to find a way to get out our information here. And, and it seemed like a very good idea at the time. [laughter]

By the time I was sitting at midnight editing No More Moanin' I thought no, this wasn't such a good idea, and how are we gonna print the next issue and what are we going to put in that? But it was, we didn't need to find a way to get out the information. And I think what's important about that is that we really were—it wasn't about putting out a journal. It was how do we make our work useful to people, it goes back to the question of what we're about, we were about how do we build a movement. And therefore we have to get this information out to people, we have to keep growing that movement, and the journal was one way of doing that.

Now, I happen to think that one of the things that we, a missed opportunity for us was not in doing some of the other things that we had talked about in terms of education, which was an ongoing series of seminars, being we talked a lot about using the oral history work to develop alternative curriculum for public schools. Those were all great ideas which we did not have the money and the resources to really focus on. But Southern Exposure, we did make work. That became a major way of getting information out. And it's, when you look back, when you look at the tables here of all of those issues, it really is an amazing legacy. I left early, I left in 1978 to go to the Highlander center. So for me to look at all of the things that, all the work that has been done since then, is just it's an amazing body of work that has been sustained throughout this time.

Just one more thing. There were three. I meant to say this earlier, there were three, three satellite institutes that came out of the Institute for Policy Studies. One was the Cambridge Institute in Cambridge, Mass. It had the people associated with that were Gar Alperovitz, Christopher Jencks, Mary Jo Bane, they had their own publication. There was a Bay Area Institute in San Francisco, California, with Chester Hartman and Barry Weisberg really focused on environmental justice. And then there was the Institute for Southern Studies.

Now the names I mentioned — the Cambridge Institute had all the Harvard academic cred and a ton of money behind it. The Bay Area Institute had the academic cred and money behind it. The Institute for Southern Studies was you know, two of us who had BA degrees, and mine was in religion. We did not have the credit, the resources. But we were where the other two institutes came to do a founding meeting of those three Institutes. They came to Atlanta. And we were a part of that network, which I think was helpful in the early days in terms of being a part of something nationally that was going on. And certainly the Institute for Policy Studies, they gave us some money in the beginning and supported our work, and were very important in what we did.

But of those three Institutes, the Institute for Southern Studies is the only one that lasted. [applause] We did not have the money, we did not have the resources. But we, we sort of knew that we wanted to create an institution that we could sustain over time, and it's the only one still alive and well.

CH: Kick it over to Leah.

Leah Wise: Hello everybody, good afternoon. I feel very grateful to be here and very thankful for all of you who put this together, but especially because so many of you in this room are so rooted in my heart for the work that we have done over the years, and so I'm really grateful to see you all.

So I came into the Institute in 1971. And I basically, first of all, just to say a little bit about my background is, I came out of the west coast, I came out of a left wing family that did both union organizing and racial justice work. I came from a culture that really celebrated and saw and witnessed workers being in leadership of those movements, and Black workers being at the forefront of many of them. And so one of the things that I came to when I came South was an understanding of and excitement about the leadership and the work that people have done before our generation, and with great respect. And I had met a number of people who had come through town, one of them was a black communist, named Pettis Perry, he was at the front of my sister's girlfriend's house, who had all these stories from organizing in Alabama, and riding the rails and in my mind I said, whew.

And then I went to school in Wisconsin and worked at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, which had both a social action collection and civil rights collection, and was sent to Mississippi in 1967 to collect materials and remembrances of the movement, particularly the summer of 64. That meant I went to all these different communities. But I also had to be involved in negotiations between the university and — well, the State Historical Society, which was actually on the university campus, and SNCC. And at the same time, I was affiliated with SNCC through a Black student organization at Wisconsin. And so the issue was, whether or not the State Historical Society — me — could actually collect SNCC papers. And the agreement was because SNCC was very, you know, anxious about government institutions, that I could go to Mississippi to collect papers of COFO, which was the combined Civil Rights Movement organization, and go to all these rural field offices, but to not take SNCC papers, and if we found any to bring them back to the office, so that was the first negotiation. There were other negotiations later.

And then I married the Executive Secretary of SNCC, and so I moved to Atlanta. And when I was there I was on the first staff of the Martin Luther King Center for Social Change library documentation project, and we did collection of movement work all across the South. So all of us have long coattails that we brought to our work at the Institute. And mine was not only having relationships with SNCC folk but actually contacts and relationships in grassroots communities all across the South from this work. So the other thing, I guess, is it to say that we were all politically active in Atlanta. So this was just a piece of our work and in a way that kind of helped, as Sue was talking about, get some of it out, but we also had other endeavors. So one of the things that actually the Georgia ACLU was right there in our offices. And so I was on their police committees. Anyway.

But I want to talk a little bit about the context, because in Atlanta at the time, this was a time where Black Power and Black consciousness was really flowering. And the way in which Black Power was being interpreted was to build Black institutions. And so this institution-building effort was in terms of education, in terms of cultural art. So there were a lot of community based groups in Atlanta doing this, even my daughter went to a daycare center, that very much was about teaching Black history and Black consciousness and awareness. So that was kind of that environment. And it was this effort at recovering Black land, and different political campaigns beginning to emerge for mayor and stuff. And then SNCC was also, the work was moving into internationalism, and particularly supported African liberation movements.

So these are kind of the dynamics but at the same time, there's all this COINTELPRO repression happening, and that I felt like I lived through because we had the — Stanley [Wise] had the responsibility, really — of dismantling the organization. And at the same time, there was the jailing of SNCC draft dodgers three, who went to jail right at this time, and then Che Payne and Ralph Featherstone were blown up. I mean, it was a heavy duty situation. I was also a part of the Black draft resistance movement, which grew out of my, one of the main works that I personally did with SNCC was in terms of anti-war work. And so even at the time, when I was in Atlanta, I was a part of the National Black Draft Resisters League, and I was actually counseling people.

So the other aspect I want to say about the times is just what was the character of history, and in the Black community, the work around what we called then “Negro history” was primarily predominantly about, “How do we write about how we are worthy people and worthy of being treated in the mass dominant society?” Not, “What is the story of resistance, and dealing with a capitalist society that has dehumanized and — and,” well you don't need to go all the way [laughter]. But, but the point is that, and then there were some, you know, some beginnings of things that were surfacing like writing about slave resistance and stuff. But the — and I think, actually, Vincent Harding has an article in No More Moanin’ about this idea about where was history going.

So in part, what I saw, and was very grounded in really, was how getting at that, including the voices of people, Black people, white people in the South in the, in resistance, trying to make a way, trying to affirm life. Those stories are required for history to be true. And I really thought everybody else, white folk, just knew a lie. And I think that's actually at the bottom of conflict today, that people don't understand the history of this country. So in a way, this was a very missionary work in a way. And then the other side of it — I'm looking at Ajamu [Dillahunt] — coming up in New York, the pan-Africanist cultural nationalist group, didn't even, they denied that Black people had a history in the U.S. and looked to the origins and influence of African culture, and even to the point of some folks deciding that it was important to be polygamous. I mean, that was traditional history. That was not the whole dominant trend. I'm saying it is a trend. So then the sense of our trying to do with history that was grounded in the people, not just professionals and that kind of leadership was really what I was interested in and brought to the Institute.

The other side to it, the other dynamic I'd say, was that, was liberation theology and Howard Thurman's influence. And this being another dynamic that was going on. So at the time, also, the sort of splits in the movement, some of which were a reaction to Black Power, the sectarianism began to surface at that time. But it was nowhere near like it was at the end of the 70s, so, at any rate.

So what I'm gonna say is that I, personally, was inspired by Ella Baker, who I had many conversations with when I was at the King Center, about all the work that she had done in the 40s and 30s. And nobody knew it. I mean, she was very central to our work — nobody bothered to ask her, what did she do, because we had this — or SNCC had this, I didn't identify with this position — but that people over 30 were irrelevant. So, so I have a lot of those stories behind me. And I felt like the importance of not only capturing that, but the importance of really surfacing and celebrating working class perspectives, was essential to correcting the historical record, I would think.

And this is where I was gonna say that in terms of doing oral history interviews, you have to recognize your influence on the people that you're interviewing as well, right. And because a lot of folks didn't even recognize the significance of what they had done, and they felt so proud, or they feel so proud, when it is acknowledged. And so that was what made this work really exciting and dynamic. And also, people, I thought, should understand workers as being intellectuals too. And, definitely the legacy of slavery, in my view, put a damper on the South of, workers are to be shunned. They are lowly, they are unworthy. And even that language of rednecks said the same thing about poor white workers. So to me, this was part of why what we were doing was a really revolutionary enterprise, because we are trying to write the record.

So I do want to say, — how many minutes do I have? I do want to say that it was a challenge coming out of Black politics and background, coming to the Institute and working in an interracial environment. You know, I was not above criticism for that. But I want to say like when, like the institution building the institutes of the Black world, which was the second arm of the Martin Luther King Center and library documentation project, were very much about, conscious about creating Black institutions and controlling our own history. But their work did not turn the lens to working class people. And so to me, what was important about being in this environment with the Institute, was that we all agreed about what were we after, and why was it important to be done.

And so I think that, actually looking back at the very first issue of The Military and the South, I was like, surprised, Damn, how do we pull this off? The first two articles are about the Black anti-war movement and the perspectives of that movement. And nobody talked about the anti-war movements being anchored in the Black community, generally. So I was, I felt like, yeah, that was why I was with these folks.

So anyway, so what I want to speak to though, is that I feel like the organizational culture and style of work that we were in, engaged in very much mirrored the methodology and principles of oral history. And so we were like, everything was about conscious collaboration, competence, shared leadership. We were, you know, we were like peers, we recognized the coattails that we brought to the table, we had respect for each other's work. There wasn't a hierarchy, which was probably the work at least most of us had come out of that, that kind of experience. And the idea that we all had different talents and skills that we could pull them all together, and not just pull them all together on the staff, but all of our friends we roped in to please help do this, please help do that. We're trying to elevate voices. So the kind of turfism and silo stuff that emerged later, this was not a dynamic that we were engaged in. In fact, were very conscious about trying to not not be that.

So I guess I would say the other thing around the like and division of labor you know, we all did everything fundraising, emptying trash cans, taking notes transcribing. But me, I was gonna draw the graphs. I mean, Bob was the chart person, but I was the one who would sit down and draw the lines. You know, and you have to remember the technology, we didn't have computers. You know, we were, we barely had a Selectric typewriter, we were cutting and pasting things. I remember the article I wrote about China, somehow a whole paragraph got on the floor and never made it in the article and things like that. But anyway, I think that the, I don't know if this is the time that we were going to do this or talk about this later.

But I want to just say that these this style of work, so much shaped, what I've done, from here on and that and trying to bring people together, have respectful relationships, you know, learn from each other, have a greater sense of what we're doing that and and every aspect of work, I guess I can think of has always has an oral history aspect to it is that — how do we give credence to what we're doing, you go to the source. And so I want to just kind of close with that. But just to say that for all the work, organizing work that I've done since that time, I always was engaged with all these people. They always got roped into one thing or another. But that's what those relationships meant. They were significant. They were real. And it wasn't that we were above struggle, because we certainly had that in some kind of difference of opinion. But we had that kind of respect and sense of honesty and truth to the work.

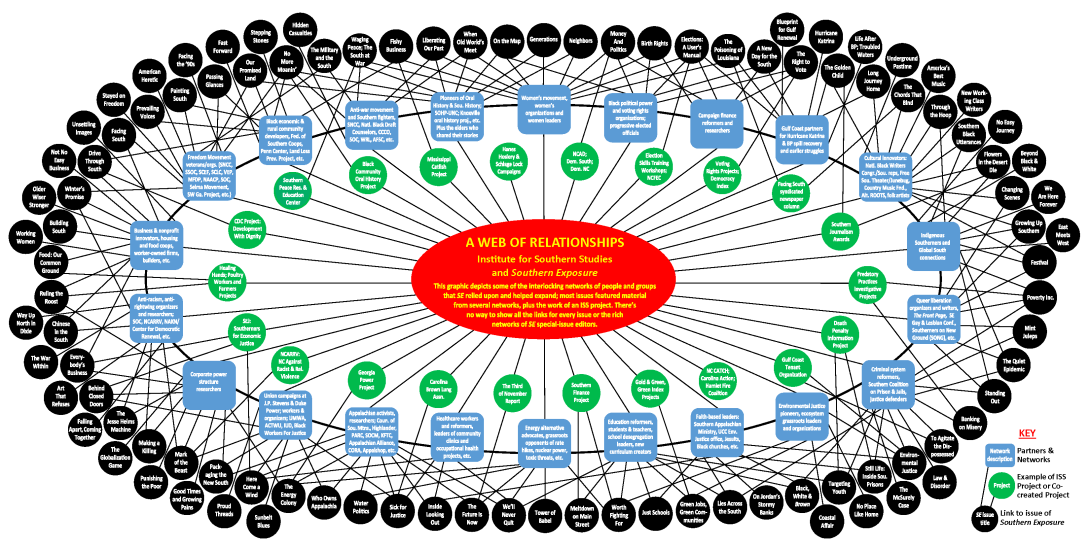

CH: Next and last and least and most, direct your attention to the right side of the stage to that big chart there, and Bob Hall.

Bob Hall: Oh yes. I want you all to come up and look at the big spider web and look at the blue boxes and the green circles. Because that as Leah was as we were doing this, this is, the Institute and Southern Exposure is a web of interrelationships that we relied on totally. And you all were a part of that. And we tried to actually help grow all of those movements. As Sue said, at the time that Southern Exposure came the movement was fragmenting but it was also blossoming and just a thousand flowers, so trying to help nurture that and keep track of that.

I'm gonna, I'm gonna start and go back. I joined the Institute as a volunteer, as I think a lot of folks in the stories that I've heard started as an intern or volunteer, I started as a volunteer when Jackie and I moved to back to the South from New York in 1970 in September, the Institute had started in March. And I started hanging around. I didn't have any money. But you know, we just had a lot of conversations and all.

I had come out of, like Sue, grew up in the church, Southern church. Single mom, raising her four kids as a church secretary. Work ethic was totally into me. I started earning money when I was eight. And I never stopped, you know. People know me as a workaholic. I am a workaholic. Sorry. That's my work balance, my life balance. My current wife Jennifer knows it well. So, but, you know, I went to college in Memphis, met Howard there, Howard pulled us, Jackie, and I into demonstrating against segregated churches. We tried to integrate them with a youth chapter of the NAACP in 1964. Howard was two years ahead of me, and also pulled me into SSOC.

And then I went off to New York graduate school, reconnected with Jackie up there and got involved in, I was at Columbia, at the Columbian bus, the takeover of Columbia buildings influenced by the investigation of Columbia, got involved in a mobile resource team for the next couple of years. Dropped out of Columbia, got involved in organizing, anti-racist organizing in crisis situations — 1968, this is right after the King assassination, right after the sanitation strike in Memphis. And the analysis of the church sponsors was that if there had been a segment of the white community in Memphis that had spoken up in favor of the sanitation workers, maybe that strike wouldn't have lasted so long, maybe there wouldn't have been as much violence, cetera, et cetera. So the idea was to have us young punks, you know, the young people go into communities in a crisis type of situation, so that we went to St. Petersburg, Wilmington, Delaware, Lexington, Kentucky, all kind of different places.

And then I wound up back in New York, working with, kind of investigating the church itself, their investments, the corporate power structure of the church. This is at the time of Dow Chemical, trying to get the churches to not invest in Dow and disinvestment in South Africa. So the power structure stuff was, was big. So when I came to the Institute, those are the kinds of things I brought was the power structure analysis, and also this interest in organizing very much. And I started right away even as a volunteer trying to dissect the power structure of Atlanta. Of course, the big power was Coca-Cola based in Atlanta, that's a big dog, and Minute Maid, which Coke had bought. There was a United Farmworkers thing.

Anyway, one thing after another, you know, we did it in ‘72. Out of, out of our many meetings, we identified the Georgia Power Company. At the time, they were trying to break the unions, they had a record of horrendous job discrimination, and they were in trying to get a rate increase from the, from the utility commission. We said, “Holy shit, this is—” and they're, you know, a public, public monopoly. But they were regulated. So how can they serve the public and all this stuff? So we organized the Georgia Power Project. And in that, that kind of pattern, and then, you know, pushing us all to be more disciplined about our work, and how are we going to get it out?

There was an integration of these acts, these organizing efforts, with the publication of the journal always, to me.

None of us were journalists, right. We were all activists. So we, we were struggling, how to do that, and keep everything going. But it relied upon, you know, these big, our friends, the networks. And part of the purpose of Southern Exposure, when you look at those old memos, it was about connecting broader to the broader movement, bringing, how do we relate? How do we contribute? And I think that was what we were doing, and at the same time, incubating more organizing projects, developing more organizing projects.

Shout-out to Jackie, she was the one that came up with the title, Southern Exposure, it comes from a book by Stetson Kennedy, but it's called Southern Exposure, an exposé from the South written in the 40s. And on and on.

So I want to hear actually, from some of you all about some of the issues. If we're going to talk about how issues develop. There are a number of editors out here.

I want to also say that it's a big thing to me that we were pioneering oral history and pioneering corporate research, and investigative research at the same time. This one little Institute in the South, a pioneer in both of these things in this, in this environment, that's, it's pretty bizarre. But it happened. And another thing that was influenced by us, from, from the [Great Speckled] Bird, our graphic designer was Stephanie Coffin, and she infused in the magazine this ratio of graphics to text and trying to, you know, make us recognize that a picture's worth a thousand words. So the graphics was a very important throughout.

I see Allen Troxler down here was one of the designers, we had some dynamite designers of the magazine through the time, so shout out really to the designers and special editors. But I know there's Peter Woods special editor, Tema Okun, special editor, Jim Overton, special editor, Fran Ansley, special editor, Jim Sessions. Yeah, the religion issue. Who was involved? Stand up, please, if you were involved in a special issue as an editor, I know even [applause] Who was a board member of the Institute, board member of the Institute, many of you all were, served on the board? [applause] Because it was a very fragile institution. It almost shut down more than once.

LW: One of the things I do want to say I forgot to say, but we had a particular character as a staff and that was we were quite audacious. Oh, yes. One story I had, I was telling Bob that I had, that sticks in my memory. We were up at the New World, no, Field foundation. Les Dunbar was the director. And Bob and I are talking to him about, you know, can you give us a shot with, I don't even know whether it was general Institute or particular issue, but you know, the reception was kind of cold. And I'm thinking well...and Bob says, can you just kick us $5,000 to get our toe in the door? Sure enough, in a couple of weeks, there was five thousand dollars. So I learned from that, yeah, we're worthy, and they need to partner with us in order to realize their mission. So—

CH: Also one of the amazing proposals that was a total failure to the National Endowment for Humanities, which was for the project.

LW: Right. Our audacity. Doing this when Nixon was president. There was some insanity in us too.

CH: Yeah. No, we really wanted to be able to have a conversation with you all. And so if people would like to make comments or ask questions to the group, we'd be happy to do that. anybody who'd like to jump in, stand up, raise your hand.

Peter Wood: I'll just follow along the audacity comment, because I was on the other end of the stick. I was a foundation officer in New York. And it was weird. I was under 30. And I, and didn't know much. And I would have the university presidents come in and suck up to me. Because they would say, I'd say well, what are you interested in? What are you interested in? And they'd have their little grocery list, and anything—"oh, yeah, we do that too," you know, "we need $200,000." And then I started meeting, first I met Charis Horton, Myles Horton's daughter. And she went back and told them, there's this guy at the Foundation, who seems to be interested. And the reason I was interested was because these people were audacious. Just—"This is what we do," you know, and one of Mike Clark came in from Highlander, he, I said, “Tell me what you do.” He said, You're not going to be interested in what we do. But this is what we do. It wasn't give me money, you know, it was, you know, if you're interested and he said, Well, come on down, I'll show you around. You know, and that was coming to the Triangle of coming to Highlander, those places. I mean, in a world that was so vacuous and so corrupt, and so isolated, this was a fresh breath of fresh air, and it changed my life.

ST: It'd be nice to hear from some other people who did special—

Fran Ansley: I’m Fran Ansley, and I told the story in the labor roundtable, but it means a lot to me. And I think it's relevant. I think that I, Brenda Bell and I came to work on the No More Moanin’ issue because of you, Sue, I think. I mean it's all vague in the mists of time, you know, but we came over and had a meeting with you and Leah, and it was all very exciting, and we were trying to understand what you were asking us to do. But I think you figured we were strategically located near Highlander in East Tennessee, we've been in Knoxville now for a long time. And the thing that Highlander could bring that y'all were just ready to go with, you just handed us this, and Highlander handed us these amazing gifts which was Jim Dombrowski's personal notes from his interviews with coal miners who had been helping to set the convicts free during the convict lease fight back in the 1890s. Here we were in the 1970s, holding these notes from the interviews of the people in the 1890s. And thinking, now we get to go interview some people who are still there in Lake City, now it's not called that, anyway. And at the same time, Myles Horton gave us the gift of his memories of being on the Cumberland Plateau in the great Davidson-Wilder strike, which I already knew a little bit about, from Eddie West's record of all, you know, so you were really instigating people, instigating people who were pretty young then to go out and find out about stuff. And then you could provide a place for them where that information got out.

ST: I was thinking this morning, Myles Horton was arrested, I think that was in the Wilder strike, right? And then he said —

FA: He was, and he said, "What am I being charged with?"

ST: And he was, he was accused of getting information, and going back and teaching it. [laughter] I always thought that that was certainly a good description of Highlander. But it's also a description of the early, of the Institute for Southern Studies and Southern Exposure, getting information and trying to find a way to teach it.

CH: Anybody else?

Earl Dotter: To those designers who recognize a picture was worth 1,000 words, I give great praise to because the venue of Southern Exposure, offered picture makers like me an opportunity to pair our images that represented individual people and their stories in a way that there was a synergy. And the combination gave great power to the message of souls and exposure. And I was always grateful for those associations and an ability to just add my part.

CH: Jacquelyn, do you want to talk?

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall: I was going — to the Special Issues question. So this is just a little story that, to me, it illustrates — I edited with two other women, a special issue on women in ‘77, I think it was and the Southern women's movement was a complete unknown territory to the women's movement of the coasts. And I think that issue really contributed to making that movement known, that things were going on in the South, that feminism was, it was alive and well in the South. But I have this letter — this is a plea for not only reading the old issues of Southern exposure, but also digging into the archives which are here now — a letter to me from Susan Brown Miller. Big-time. She had just published against her will, a big book about rape, a big New York feminist, and we were publishing or republishing a letter from Anne Braden to anti-rape activists, reminding them of the use of rape as a weapon against black man, you know, don't forget this complicated gender-race thing. And so I wrote to Susan Brown Miller and asked her if she — she criticizes Susan Brown Miller's book, of course, as you know, as she should have — and Susan Brown, so I wrote to Susan Brown Miller, a very obsequious letter saying, would you like to respond to Anne Braden? And she writes me back this two page blistering letter. You have ruined my day, Anne Braden doesn't know what she's talking about. And I was just like, Okay, that's New York. I —

ST: She later wrote a review of a book that I worked on, Deep in our Hearts: Nine White Women in the Civil Rights Movement, and she didn't like that book either.

CH: She mostly liked her own books.

Eric Frumin: So another, another view from New York. [laughter] I'm just curious, how worried were you about infiltration about, you know, people, FBI, whatever other versions out there locally, infiltrating, you know, trying to screw things up, spying. Did you have to deal with that internally at all. I'm just curious whether that was a presence coming out of the traditions that you had come from.

LW: I don't remember that being a part of conversations with us at the Institute. But in the community in Atlanta at that time, it was very real, and especially with the SNCC's organization and the work going on. And so there was a lot of, I mean, some of the police officers, for example, who trailed SNCC people, folks knew them, you know, they were aware of that, but there were others where more of the agent provocateur thing was resurfacing. So that was a part of the growing black movement at the time, that that was happening, it was conscious and, and especially as the work became more international, that was also more present.

BH: There was even, there was also even in the Georgia Power Project, awareness of an agent provocateurs, and infiltrators trying to make you do more outrageous stuff that you wanted to do. Because they wanted to then have an excuse. So you had to be very careful about what the tactics were. And the Bird offices, you know, were fire, were burned, probably in ‘71 or so. I mean, this, there was a lot of awareness, and COINTELPRO. And it was, there was some paranoia. And needless to say, I'm always aware of my phone. We don't say stuff on the phone. Unless you. Yeah, there's still awareness of that it goes on continually.

CH: No, it's so funny that even when we were having our discussions about having this event, we didn't really want to make it that public, because the Klan might come. But there's still there's still a concern. We're living in the middle of a war about history right here. This campus. We're still paranoid.

LW: I want to say a couple of things about the Southern Black Utterances Today journal, which I co-edited with Toni Cade Bambara. And the reason that we did, now I just kind of thought about this, because of the role that Southern Exposure played of communicating the South to the rest of the nation, and in this case, this was a conscious effort to bring southern Black writing into the Black rights movement nationally, which in all the volumes that had, were present, nothing was there from the south. So that was the intention behind that.

And I just want to say that, from the the experience of being exposed to so much of what the South is, and was that it became part of the articulation of our work. And I remember when Bill Troy and Doug Gamble, who were from Tennessee, and I were a part of this grassroots organization around plant closings in New York. And we were exposed to all these this organizing happening everywhere, and were like, are we just bad at organizing? Why is it that we were so far behind in everything, and it just made us began to articulate more of the really structural relations of the South, but it became something that this was the groundwork for that and so I think that was one thing that was that has been a major contribution.

The second thing I just have to say, which is around the Southern Tenant Farmers Union work is that when we were doing all these interviews with H.L. Mitchell in our office in Atlanta, the story of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union looked a lot like what Donald Grubbs' book was, which was, there are these white socialists in Arkansas, and they are working with these Black tenant farmers and they're communicating to money people in New York. And that was the work of the Southern tenant farmers union. But when I went from community to community across Arkansas from Central Arkansas to East Arkansas, I learned this organization was practically 95% Black. And these were grassroots organizations on the ground, some of them were interracial chapters, and most of them weren't. a lot of women leadership, the black leadership in the organization, especially vice president was intentionally black, because they felt that they were actually the chair, they would get nothing but absolutely slapped down.

So just to say the truth of what the work was, and then to learn that the people involved in the Southern Tenant Farmers Union were also the same people who hosted SNCC people who came down or other students who came down in the movement. So this is a sense of the movement and how you, you know, you work and build on the shoulders of others, it was very much present in that work. But, you know, had you not gone and talked to everybody, we would not have had that. So that's why I think oral history is a revolutionary enterprise.

BH: Can we get Eric Bates, who was the editor in whatever the period was — tell us what the period was. I know, at the time, when we were doing stuff, there were six or seven of us trying to piece together things on a little pieces of board, had no technology. And then a new generation, a real journalist and editor came along to keep the magazine afloat.

Eric Bates: I was here from ‘87 to ‘95. I think to what you're saying some of the, you know, one of the changes at that time was technological, it was the first time we started producing the magazine on a computer. My last, my first issue was with Peter Wood. And I remember going to the airport and realizing that a piece of the cover had fallen off, I had to race back and get find the piece at the office and put it through the hot wax or and put it back on. But after that issue, we started being produced on a computer. So that was a big change.

But I also think that there was a period when the Institute and the left in general was thinking about this question of audience and how do we get our audience our message out to a wider audience, the left was very comfortable sort of preaching to the choir. And I think the Institute had always had sort of these three legs of academics, activists, and journalists, but tilting much more heavily towards the activists and the academics. And I think we began to kind of experiment with how can we package our stories in a different way? How can we do the same work and have it have the same Integrity and authenticity? But how do we get it out to people who might not otherwise see it. So I think that was a new, relatively new kind of concerted element, and produced all sorts of tensions, because the translating function is different than then speaking to your own selves function. And so that forced us to think about it, what we were doing in all kinds of different ways.

But we still tried to make sure those three legs of the tripod were there. So when we did something like the poultry issue, which was mentioned earlier, every issue we did, had an investigative journalism aspect, where we tried to look at the power structures. And it had an oral history aspect where we tried to hear directly and in an untranslated, unfiltered way, from the people whose real experience was driving our work, and tried to have a historical lens through which we understood how we had gotten to this place, and the models that have come before. And so I always felt like integrating those three elements was the the through line of all the institute's history, and it was done in different ways and different measures at different moments. But that was what made the Institute's work and southern exposures work so unique is that it drew on those three different strands of activism

CH: Are there any questions from the Zoom audience? Okay, we're good.

ST: Chip, you should say a few things. Because you were actually right behind us.

BH: Also a founder.

CH: No, no. Any other comments? Final words? Oh, good.

Audience member: I have a question. You've talked about Atlanta. How'd you get here?

CH: Bob and Jacquelyn.

BH: Yeah, so in summer—Jackie got a job as director of—

JH: First to get a job! [laughter]

BH: Honest work! Got the job at the UNC Oral History Program, you know, to come and start it in the summer of ‘73. So the magazine, we'd just done one and a half issues to the July, you know, the two issues. So, and the business, we didn't talk about the business of making the damn thing work. But it's a small business. And that was a lot of work. And other people here can talk about it, but that, so the business operation moved with me and Jackie, to our house. And for the next couple of years, the business operation, much of the magazine, ran out of our house. And I would go back to Atlanta, because Stephanie was still there doing the layout and stuff. And we were using free some of the technology at Emory University, we then came here and started using free technology at Duke. Those kids didn't care. It was free, they didn't pay for it. [laughter] I mean, so, anyway.

Nancy Maclean: Yeah, I just want to say as like the next cohort, I guess, of people, you know, excited about this work. I? Well, I started college in 1977, and then graduate school in 1982. And there were two journals, popular journals like this, that were just crucial to my formation, you know, my thinking and activism and Radical America and Southern Exposure. And when I was starting graduate school, in the ‘80s, it was just amazing to come across that journal, like what was lighting up history was the new study of slavery and the new studies of the South and worked by Jacqueline and other you know, so many other folks about about Southern history, but I just love Southern Exposure. And it was just so rich. And so in today's words, intersectional in such an amazing way. But I also want to say too, I really appreciate it the visuals, you know, that people have talked about, but the visuals of the magazine and the incredible photography and graphics and cartoons, but I remember there was a picture of, and I don't know who took it, I don't think it was Earl Dotter. But there was just a picture of one of the issues that had a father and daughter. And, you know, the father really looked like he had a hard life. And he kind of had, you know, cut off sleeves. And he, but he was holding this girl with such tenderness, that it just moved me deeply. But it was, and he was white, anyway, it was just so beautiful. But that and among many other photos, I made copies of it and hung it in my office. But anyway, when I was at Northwestern, one young woman said, Oh, is that your father? [laughter] Look at this photo, you know, and what you see in it. So I just wanted to share that.

But I also wanted to pick up on something that a few of you made reference to, Leah, you in particular, about what happened in the later years and kind of the fracture and the sectarianism. And I'm just wonder, like, now looking back on those years, how you would explain it. I mean, on the one hand, there was this kind of left developing that could get very sectarian. On the other hand, the movements were, as you said, like multiplying and exploding in all these exciting directions. But I also wonder if on reflection, foundations contributed to some of the fracture, you know, in this situation that we see now, where foundations often have groups who should be working together competing for funding and therefore trying to distinguish themselves from one another. And I don't think that was the case for the Institute for Southern Studies. But I wonder if you're, if kind of the movement world that you were connected to, some of that fracture had to do with that, you know, that need to compete or for support?

LW: Well, I have, how many, ten seconds? Thirty seconds? That's a great question, but I'll answer on two fronts that I've experienced.

First of all, I think the role of foundations and its influence on fracturing, the movement was that it really basically put the movement in silos, and people had become experts in a very narrow piece of work. And that got funded and people competed for funding within that slice. So there was a lot of turf ism that surfaced. And so I think that's what was full blown. In the Black movement and civil rights, I guess, work, I would say, there was a lot of influence of the Marxist-Leninist work that was mainly in New York, and we call the alphabet soup stuff, but both were, you know, especially in the African liberation movement, because they were aligned with different countries, China, Russia, you know, they were different politics that cause that kind of stream to happen.

What broke us out of it was the murders in Greensboro and the I was, what brought me back actually into working and organizing was having that demonstration that took a major issue, Jim Lee is here, was very instrumental in helping get that off the ground. But at that time, finally, all these folks who had been battling each other to the point of, well, I don't need to go to the point of, but but the point is that here was this greater enemy in our midst, and it was the first time that people came together to pull off that demonstration. We had a planning meeting in Atlanta. It was a conference of kinda there were 400 people there and about 30 of us ended up sitting on the floor for all night long to bring together — this was one end CWP and the other end SCLC of "we're marching with guns and, no, what this is a, you know, peace movement." So it took, I mean, it was very intentional, to bring people back together, but that was a pivotal moment. And so then there were different opportunities. My work was in creating networks was actually to provide the arenas for people to come in to work together. But there were other opportunities as well.

CH: We're, I mean, we hate to end any conversation, but we need to leave the stage. [applause]

Tags

Olivia Paschal

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Virginia. She was a staff reporter with Facing South for two years and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South's year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also led the Institute's project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive.