Five questions with Marc Miller

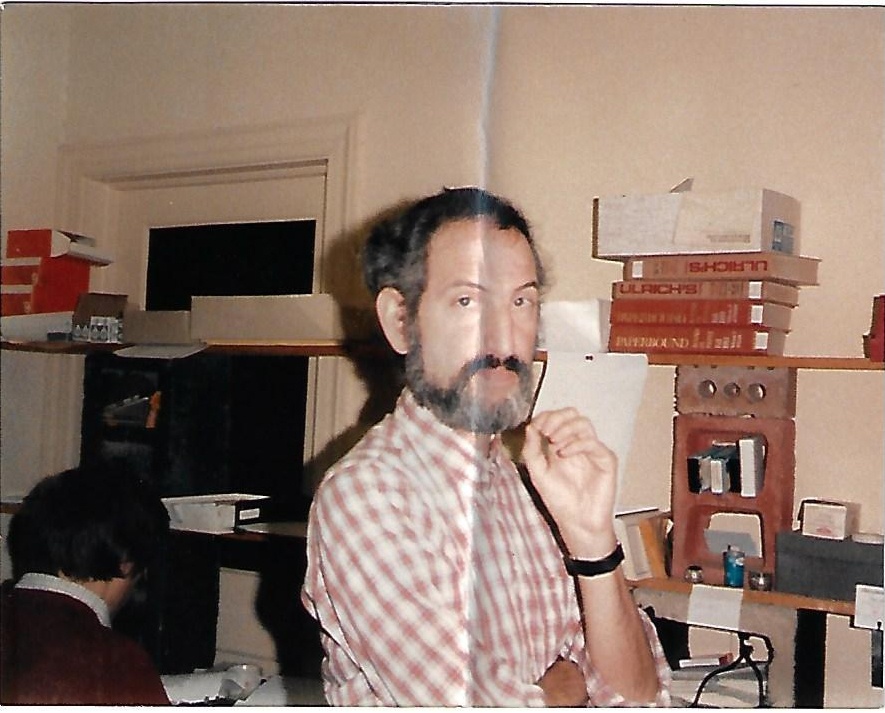

Marc Miller in the Southern Exposure offices circa 1985. (Photo courtesy of Marc Miller)

Marc Miller was on the staff of the Institute for Southern Studies and Southern Exposure for eight years, from 1977 to 1985. He started as a volunteer drawing unemployment insurance from the state of Massachusetts — where he worked as the associate director of the MIT Oral History Program following graduate school — and didn’t intend to stick around for as long as he did. Marc contributed to many Institute projects, most notably the Elections issue in 1984, which was accompanied by five statewide workshops bringing organizations together around winning in the electoral sphere. He also edited Working Lives: The Southern Exposure History of Labor in the South, which was the Institute’s first book.

For the past two years, Marc has been volunteering once again on another Institute project, this time helping to digitize Southern Exposure by pulling text from magazine PDFs to be uploaded to the digital archive. When he finished that work a few weeks ago — a monumental achievement, for which we are deeply grateful — we asked him to answer five questions about how Southern Exposure and the Institute impacted his work, his life, and his politics.

Where were you in your life when you worked at the Institute for Southern Studies and Southern Exposure? How did your work at the Institute play into what you have done since?

I had just finished my Ph.D. in the winter and decided to volunteer at ISS until finding a teaching job in the fall. I was also preparing to submit my dissertation to publishers. It was an oral history that eventually became The Irony of Victory: World War II and Lowell, Massachusetts.

It was the combination of oral history and activism that attracted me after Ted Rosengarten told me about Southern Exposure, and I met several staff members at an Oral History Association meeting in Asheville. It turned out that the Institute’s combination of activism, history, and journalism would be my career, except for some part-time teaching. After Southern Exposure, I moved back to my home in Massachusetts, where I was an editor at various publications, both mainstream (but leftish) and activist. The fact I had worked at Southern Exposure opened many doors, including Resist foundation, Technology Review magazine, Dollars & Sense magazine, The Women's Educational and Industrial Union (now the Women’s Union), the Oral History Center, and the Organizing and Leadership Training Center (now the Massachusetts Communities Action Network).

What drew you to spend so much time volunteering with the Southern Exposure archival project?

For one thing, my personal debt to the Institute for Southern Studies is huge. The work at ISS, my colleagues on the staff members and among friends of the Institute provided my real graduate education. And rereading old Southern Exposures for the archival project reminded me how powerful the magazine was, how important it was to activists, and what working at ISS meant to me personally.

As you worked through decades of the magazine, you were consistently sending me pieces you thought stood out in some way, or spoke to the current political moment. Which was the most interesting or surprising of these finds to you, and why?

Back then, I may have taken for granted most of the material. In retrospect, the pathbreaking oral history work and articles by Julian Bond, Peter Wood, Mab Segrest, Anne Braden, and many others remain powerful and resonant today — if sometimes overly optimistic when you look at the South and the nation today. Perhaps most surprising was how good (and not dated) the fiction was, especially since my interest in short stories is not great and never was.

Working through this archive as you have is also working through moments in history that you lived through and were deeply involved in. Do you see any part of the last several decades differently, having relived it in the pages of Southern Exposure?

As in any retrospective look, reality balances memory. We were, perhaps, naïve about the possibility of the South leading a progressive tilt in electoral politics. These days, I take all election predictions, especially the more hopeful ones by progressives around elections and unionization, with a hundred grains of salt. On the other hand, rereading Southern Exposure history, as with the nation’s history in general, offers a reminder that progress has been made in some respects. In a symbolic instance, Confederate flags no longer hang in Southern government buildings. De facto segregation is gone. And in 1976, when I got to Chapel Hill, where the offices were that year, gay rights had little if any respect on the Left.

What use do you hope people will make of the digitized Southern Exposure archive?

In 1924, Gertrude Stein wrote, “Let me recite what history teaches. History teaches.” I’ve held a hope over the years that she was right. That said, activists today can find both precedent and inspiration in Southern Exposure, both its current events pieces and its history pieces — just as New Leftists like me in the 1960s and 1970s could draw models, inspirations, language, and challenges from many aspects of the “Old Left” from the 1930s.

Tags

Olivia Paschal

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Virginia. She was a staff reporter with Facing South for two years and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South's year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also led the Institute's project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive.

Marc Miller

Marc Miller was a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies and Southern Exposure for eight years. He is now a senior editor of Technology Review magazine. (1986)

Marc Miller is associate editor of Southern Exposure. He edited Working Lives: The Southern Exposure History of Labor in the South, published by Pantheon Books in 1981. (1980)

Marc Miller is an historian on the staff of the Institute for Southern Studies. He is currently editing a book of first person accounts of work in the twentieth century. (1978)