The Adidas Generation: Reflections on Student Writing

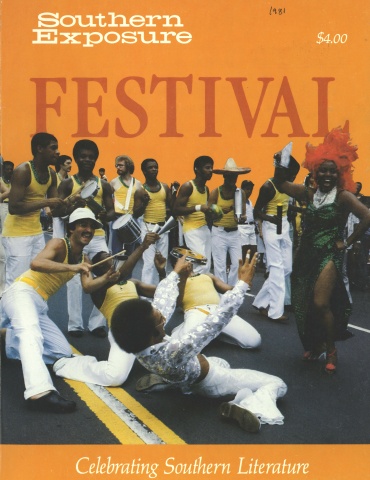

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Max Steele teaches creative writing at the University of North Carolina. He has published stories in The New Yorker, Harper’s, Esquire and Mademoiselle and is the author of several works of fiction: When She Brushed Her Hair, The Goblins Must Go Barefoot and The Cat and the Coffee Drinkers. This sketch of student writing at a largely white, mainstream university was written two years before Ronald Reagan’s election.

From the narrow fenestrations of Chapel Hill’s Greenlaw Hall, a paranoid classroom fort planned in the mid-’60s apparently against students rather than for them, I can look into the sunny Pit where body-proud Carolina students are basking, men and women with their golden legs stretched out in front of them, studying the tabloid list of Courses Offered. Who are they and what do they dream, this Adidas generation?

I believe in dreams and I have faith especially in the collective dreams, those marvelous stories that are read in creative writing classes and which form, reveal and help define a college generation. Listening to these stories over the years, I have come to comprehend what James Baldwin meant when he wrote: “Although we do not wholly believe it yet, the interior life is a real life and the intangible dreams of people have a tangible effect upon the world.”

I think, for example, of two stories by students from a dozen years ago that I recently came across. I remember that when I first read them, they too seemed new and strange and powerful to me — and quite foreign.

In one, a young stockbroker goes to his office on a Saturday to complete work he has not been able to do in his highly competitive work. His desk is not in the office which he has shared for a year with two other junior members of the firm. He searches the offices and then, by chance, discovers his name printed on the door marked “Men.” Inside, his desk and chair have been installed in front of the urinals. All his papers are in order; the telephone has been connected and there is even a carpet on the floor. At first he thinks it is a joke played on him by his colleagues; but as he stands there listening to the piped-in Mozart, the telephone rings. It is his boss asking him how he likes his new office. The young man says it is a very funny joke but an elaborate one. The boss assures him, in a voice informative but not punitive, that it is no joke, that that is where he will be working. When he hangs up, the young man calls his wife to get a babysitter and come over. When she arrives she realizes it is not a joke: her husband will be working in his new office. They agree to leave the baby with the sitter for the rest of the afternoon. They buy a bottle of brandy and go back to their flat.

In another story, called “Above the Super Market,” the reader finds himself in a walnut-paneled room at a long table with leather chairs where a meeting is going on that at first glance would seem to be that of a board of directors. But then we listen. A young man, Bradley Martin, is being questioned about his habits by the board, which apparently already knows all the answers and can tell immediately whether he is telling the truth. One of the inquisitors is a smooth, Madison Avenue type who calls Bradley by his first name and tries to persuade and coax confessions from him with his obviously false friendliness. Another is an older man, a confidant, a father-confessor, who appeals to him with wise, gray eyes from behind horn-rimmed glasses. Several are nondescript. But each is a man of some specialized power. The last man is shaven bald, wears a turtleneck sweater, has a tremendous chest and arms; and upon a signal from any of the others, lunges at Bradley to choke or hit him until he confesses whatever needs to be confessed.

The odd part of the story is that there is nothing to confess; and it is this emptiness which the lad is attempting to hide. But the inquisitors want all the details of his empty life. At last, above the sounds of the cash registers in the supermarket below, the hero confesses all: he exchanges bills at the bank once a week for change, not because he likes to run his hands through the coins as they accuse him of doing, but because he makes extra money by finding rare coins to sell to dealers; true, he has a lover and sometimes he cries, as they already know, on her breasts, but that means nothing to him. He has no joys, no ambitions. The confession rendered, he is turned loose. We do not know who his inquisitors are or what his answers mean to them.

Today, after seeing the trials of Watergate, we know that these stories written five years before the media exposés have a certain accuracy: in a metaphorical way men did have their desks placed before urinals and were soothed by piped-in music. We know that often useless facts about individual citizens were gained from rooms above the supermarket and from the files in doctors’ offices. Sometimes it seems that there are in the air prophetic stories with compensating themes waiting to be captured, brought down, netted with words by the writer of whatever age who is sensitive, through some emotional need or moral indignation, to their hovering presence.

I recall also a certain sort of story by women writers which began appearing with some frequency on some campuses in the mid-’70s. There were many variations but the plot line was essentially the same. A young woman is packing to leave her apartment, a young man helping her. She looks about, studies it as if she may never see it again. The young man is anxious, attentive — a bit, one realizes on second reading, remote and cold. He helps her with her bag into his car and drives her to the hospital or clinic. Only then do we realize that the serious business we are reading about is a first abortion. There is a brief, seemingly tender farewell. Details of the hospital, of the operating room, are usually missing. But always there is a nurse afterward who looks at the patient through her glasses or over her glasses or through steady gray eyes in which we cannot detect an attitude. The last scene varies. Sometimes the woman is phoning from the hospital to the empty apartment before going to sit on the floor of her room, nursing an imaginary baby, or playing with a doll bought for the child at a happier time. Sometimes she is back in the apartment discovering that the young man has packed and left. Here too she sits on the floor and sometimes draws her knees up to her forehead. She does not feel like crying. She feels empty.

A variation here before me, by a writer from Mississippi, begins after the operation and has the subject refusing to leave the soothing warmth of her tub, where, we learn from dialogue with the young man, she intends to stay during most of that day, just as she has been doing each day. Finally he urges her to leave the tub, the steamy bathroom, to put on new clothes they have bought her, to go with him to the cocktail party where they will see friends they have not seen for almost two months. She concedes and seems in her new clothes to be a stranger to herself. At the party her laughter sounds too loud to her, like someone else’s laughter and then above it she hears a baby crying in the room above. She makes her way through the loud cocktail party noise and up the stairs where she stands in the door of a nursery; then she enters and sits a long time by the empty crib, not knowing that the baby has been sent across town with a babysitter. When she looks up the host and hostess and her husband are staring at her from the doorway. She explains to them that she came to comfort a baby she heard crying. The husband helps her down the stairs, through the kitchen and back to their apartment, where she lets the tub fill with warm water.

In the late ’60s advertisements for safe abortions first appeared in college newspapers throughout the South. One does not know to what degree the writers of these stories were familiar with the experiences, but certainly they knew someone down the hall or back home or somewhere who had suddenly faced, alone and often in hostile circumstances, a painfully personal and complex moral question. The stories appeared and then they disappeared. But the feeling of abandonment and hallucination and grief was so strong in them that I think often of the woman analyst who maintained that the most important day in any woman’s life is the day her first child is born. If she is right, I wonder if someday we will hear of a new blend of depression and bitterness (or independence and political activism), among certain thousands of middle-aged women who in the early ’70s first experienced the birth ritual as an abortion.

The analyst commenting on the significance of birth in a woman’s life was, in a sense, completing Freud’s statement that the most important day in any man’s life is the day his father dies. Years before Freud, writers everywhere knew the traumatic impact on the family of the father’s death. Changes in the economics and politics of family life, however, have mitigated the trauma associated with a father’s death, as well as the traditional view of women being primarily childbearers. Again I have my ears tuned to those younger writers who have never quite turned away from the tradition of filial devotion, or who redefine it for their generation.

During the the ’60s the father, along with all figures of authority, was often held in contempt. But for the generation now emerging on Southern campuses, the father appears with frequency and persistence as a figure to be studied, comprehended and looked at with compassion and love. Several of the best student writers of the past few years have written father stories that, when read aloud, have brought to the class that special silence that is more rewarding than applause. The incidents, the fathers, the sons are almost ordinary and it is only the moment of identity that lifts them to that special level of good fiction.

In one story a college student is having insoluble trouble with his girlfriend and goes home without calling her to break a date for the following evening. At home his parents have argued; his mother is besieged with anger, and the guilty father has taken refuge away from home. But the grandfather invites the young man to go fishing and there, in the steady rhythm of casting and reeling in, the grandfather says only one sentence, that he too has had trouble with women. It is enough for the boy to feel a great kinship with his grandfather, with the father, and back at the house he calls the young woman to tell her he will be back but a little late.

In another story a father and mother, an older son and daughter and a younger brother are driving at night, hoping to get across the mountain between Asheville and Tennessee before dawn. For a while they sing and it is the best of moments in a happy family with the father teaching them army songs. Gradually, one by one, the others go off to sleep, but the older son sitting next to the father is determined to stay awake to help keep the father awake. They talk little if at all, but are aware of the changing pressures of their bodies against each other as the car swings around mountain curves. At the crest, at a lookout point where it is claimed by a sign that five states can be seen, the father says, “Who’s going to take a leak with me?” And the son says he will and follows him proudly to the edge of the cliff.

In still another story a lawyer and his son go through the backroads to the grandfather’s Arkansas farm. Neighbors (mainly black) have encroached and are using the backyard as a place for their all-day horseshoe games. Upstairs in the empty house the old grandfather is dying of cancer. Beside him on a chair are the masculine symbols: his pocketwatch keeping perfect time and his pistol, both of which will be inherited by the father and then the son. The son knows that he has been brought here to observe the old man’s patience and courage. As he and his father go down the steps to pitch a hospitable game of horsehoes with these neighbors who have moved their game here where they can tactfully look in on the old white man and attend his needs, the son wants to put his hand on his father’s shoulder but doesn’t.

In a final story the young man has returned home to be with his sister and his father, an epileptic, during the funeral and cremation of the mother. In the final scene, grotesquely comic and tragic, the father is seized by a fit while taking the box containing the ashes up the stairs. He grabs the stair rail and in his fall brings it down with him amid the plaster dust and ashes which coat them all. Out of this chaos, the author brings a superb order: “I stand straighter than my father sits, and I look down on his rounded shoulder. I know I do not need to stretch to catch his words. I know there is more to find out, nothing hidden from me that is not hidden from my father. I can never know what is hidden from him, or, if I knew, point him toward it. I have joined in the hunt that grown-ups have, of finding the end of my life. No longer a fumbling at the top of the stairs, or landings interposed. He has done all that for me, and I know that his problems now are insoluble. That he is not weak, but that the self-contradictions and involutions of his life have piled up, incremental as steps. And who can guess my future inturnings before I am balled up in the sheets, breathing shallowly, rapidly as I talk, each shortened and automatic breath a word, the sentence of death being read. There it will make sense, there at the end. All my father tells me now, truth delayed.”

Each of these stories and a dozen more not quoted, many of them by the most talented young writers in the South, have these things in common: the father or grandfather is a man to be admired, but the idea of the father creates a distance between him and his son; the mother is absent by death or divorce, or weakened in her presence by depression or anger or problems of her own; there is a shared moment of poignant silence (poignant because the author asks for less sorrow than the reader is willing to give); the silence is broken by trivial words; and then there is a moment in which the boy feels his father is a man who needs his friendship.

The stories have a great deal of daydream in them as well as memory. The student writers may speak for their peers who, born in the late ’50s, grew up during the ’60s in the most permissive atmosphere this nation has known, with the least paternal guidance and restrictions, and who feel the urgent need for such intense, rare moments to complete their identities as adults. One of my colleagues, who is renowned for his ability to show the connection between literature and life, states without a doubt that the restrictive Victorian father is ready to walk upon the scene again. It is interesting to me to re-read these stories, to look out on the dazzling view from my window, to realize that perhaps these are the young men and women who will usher him upon the scene and that he will bring with him his strict ideas about God and family, the rituals of man hood, the confinements of womanhood and the proprieties of dress, decor and decorum.

Tags

Max Steele

Max Steele teaches creative writing at the University of North Carolina. He has published stories in The New Yorker, Harper’s, Esquire and Mademoiselle and is the author of several works of fiction: When She Brushed Her Hair, The Goblins Must Go Barefoot and The Cat and the Coffee Drinkers. This sketch of student writing at a largely white, mainstream university was written two years before Ronald Reagan’s election. (1981)