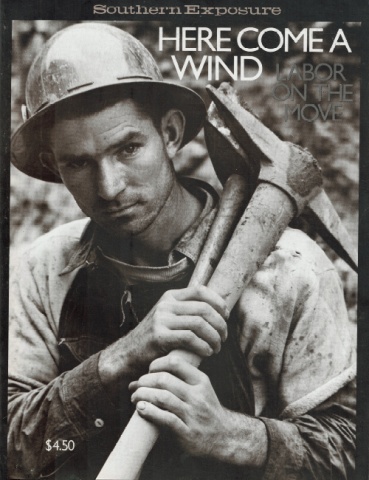

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

On April the thirtieth

In 1933,

Upon the streets of Wilder

They shot him, brave and free.

They shot my darling father,

He fell upon the ground;

'Twas in the back they shot him;

The blood came streaming down.

They took the pistol handles

And beat him on the head;

The hired gunmen beat him

Till he was cold and dead.

When he left home that morning,

I thought he'd soon return;

But for my darling father

My heart shall ever yearn.

We carried him to the graveyard

And there we lay him down;

To sleep in death for many a year

In the cold and sodden ground.

Although he left the union

He tried so hard to build,

His blood was spilled for justice

And justice guides us still.

You know the song I wrote. It was published and I didn’t even know that until one day my son was up in the shopping center and he found this book. He came in and said, “Mom, did you know that they’ve got that song you wrote in here when you was a kid.” I said I didn’t know anything about it. Sure enough, there it was - in an old-time song book. They had took it upon themselves to publish it and just taken for granted that it was alright, but I wouldn’t have had that done for nothing.

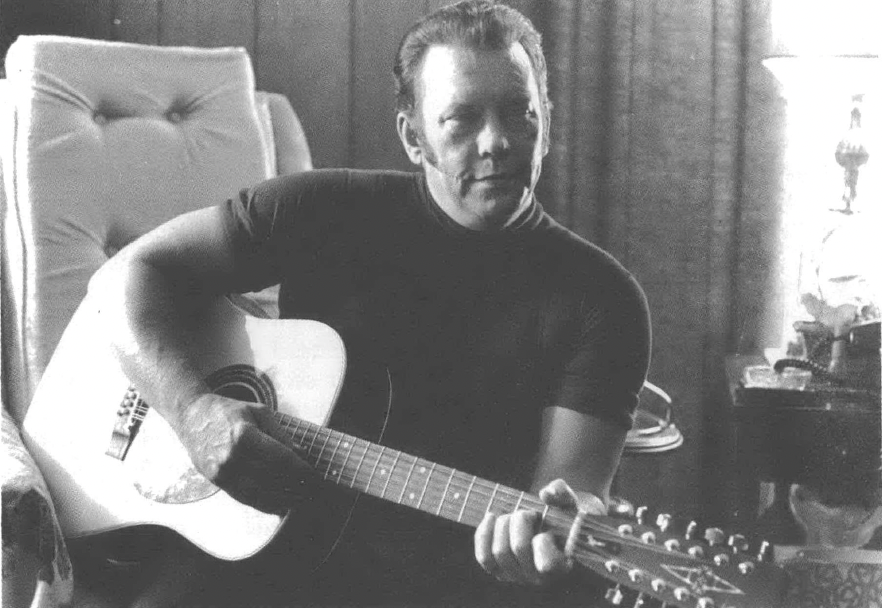

I was real sad when I wrote that song because we were having a hard time and I was a kid that loved to sing, and I loved to try to play the guitar. I just decided that I would try to put some words together and I did. You, know, the people just really wanted to hear it everywhere I went, wanted me to sing it, you know. I really felt just like the words I put in the song. I felt that very way.

They paid me for the song, though. They paid me fifty dollars for the song, two publishing companies did — after they had published it. But I said, fifty dollars is fifty dollars. I signed a contract that I wouldn’t do anything about it. I didn’t want to get revenge on anybody; I just wanted what was coming to me, that’s all. That’s what I feel I should have.

Two years ago, Southern Exposure published an article entitled “Davidson- Wilder, 1932: Strikes in the Coal Camps” in the Winter, 1974, issue, No More Moanin’. Edited by Fran Ansley and Brenda Bell, and based largely on oral interviews with people still living in the area, it was a grim retelling of the East Tennessee miners’ fight to preserve their union. They did not succeed. The solidarity and toughness of the strikers and their families could not overcome the powerful clout of the coal companies (assisted by the National Guard) and the attrition rate of desperate miners who returned to work in order to feed their families.

One man, Barney Graham, stood firm in his resolve to keep the United Mine Workers in Fentress County. The miners elected him checkweighman—the person who makes sure they get credited with the tonnage they mine. When the men walked out, Graham organized secret meetings in the woods and helped get food and clothing to strikers’ families. To the company, he was the most visible symbol of resistance; to the miners, he was a “standing up man for the men.”

On April 30, 1933, Barney Graham was gunned down by company thugs in the streets of Wilder-shot 11 times and then pistol whipped, just in case the strikers had missed the message. His step-daughter, Della Mae, age 12 at the time, wrote a song about her father’s death that became known as “The Ballad of Barney Graham."1 Like many other struggles of working people, the history of the Davidson- Wilder strike has not been preserved in the official texts; it is remembered primarily because of Della Mae’s song.

At the time the article was published in Southern Exposure, we did not know how to locate Della Mae Graham. We knew only that she had married and moved away from the area. After the article appeared, we learned that she lived in Ohio, and we sent her a copy of the issue. Some months later, we received a note from Barney Graham, Jr. We did not know until that time that Barney Graham had a son; he was three at the time his father was shot down. Another daughter, Birtha, was six.

The years following the death of their father were extremely hard for the Graham family. Della Mae married when she was thirteen, partly because she was “scared to death.’’ Her husband, Jess Smith, became a second father to the younger children. Their mother suffered from epilepsy and had no medication available for her “spells.” Barney, Jr., was also plagued with illness. Grocery staples that were purchased from the small monthly welfare check often ran out before the end of the month, forcing the younger Grahams and their mother to move in with Della Mae and Jess. The family took care of each other. Each other was all they had, really.

The UMWA, for which Barney Graham had given his life, was not strong enough to offer any real help, and the family still speaks with lingering bitterness and dismay that the union didn’t bother to come around and see how they were making it. One week after Barney’s funeral, Della Mae traveled to Washington, D.C., with Howard Kester to speak on behalf of the miners. She remembers that a great deal of money was raised that evening. She remembers, too, that she was given only $5. It didn’t go far.

Like many others, Della Mae, Jess and Barney, Jr., moved north in the early ’50s looking for jobs that offered steady pay. Like the others, they went where they had kin; for them it meant Dayton, Ohio, where Birtha and her husband had settled earlier.

Della Mae continued working as a housewife and mother to her four children. Her husband Jess went to work in a sheet metal plant, still suffering from black lung, his only legacy from nearly 23 years in the mines. In 1969, he was killed in a car accident. Barney, Jr. went to work for the National Cash Register Company (NCR). It was, he thought, a good job. But as conflict developed between workers and management, he supported the organizing drive of the United Auto Workers. In March, 1975, after 24 years, he was laid off. Once again, he felt the union was not much help.

Our correspondence with the Graham family in the year following publication of the article led us to request a follow-up interview, and they graciously assented. In July, 1975, we met with them in Dayton where Della Mae is currently living with her son Mike. Barney, Jr. and his wife Florence live in nearby Waynesville, Ohio; Birtha has moved to Florida.

We talked about a lot of things that day: the warm remembrances and deep respect they all share for Jess Smith; the difficulty they had in adjusting to the industrial North and their continuing ties down home; and the ambivalence they still feel about the need for working people to have unions, balanced against their own personal, and mostly painful, experiences.

As the afternoon progressed, other members of the family drifted in. After awhile we found ourselves snapping beans from the garden and listening to Barney and his daughter Peggy sing some good country music. We heard Peggy speak movingly of the pride she feels in the stories about her grandfather. And finally, after much coaxing, we persuaded Della Mae to sing “The Ballad of Barney Graham.” The interview excerpts that follow are mere bits and pieces of that day.

The CIO unions in the ’30s were fragile coalitions - held together against tremendous odds by the courage and perhaps the sheer desperation of working people who simply didn’t have that many options. The coal camps were organized by the United Mine Workers at great personal costs; the sit-down movement that brought success for the United Auto Workers, likewise took its toll. Today the UMWA and the UAW are two of the most powerful, and wealthy unions in the country. The Graham family has contributed more than its required share to the successful history of both unions.

EAST TENNESSEE

Della: Dad never said a lot. He was a man that never talked much about his family. Nobody knew where he came from. He came into Twin, Tennessee, and Mom and him got together. She was working at the Twinton Hotel at that time, making beds and doing dishes; that’s where she met him.

I remember the first time my mother brought him to our home. I was five years old. I liked him very much, but at that time I was a kid that really was a grandpa’s girl. Nobody was like Grandpa, you know. My mother lived with her mother and father when I was a little child and Grandpa was very good to me. They must not have wanted her to marry him, because after Mom and him got married, they just dropped us. It was terrible, really terrible.

My grandfather and her brothers separated my mother from my regular father. He left when I was a month old. He never saw me from then on. Mr. Graham was the only father I ever knew, and he was good to me. He did the best he could to provide. Of course, as we said, a lot of times he would take food from our house that we could have used, to help the next door neighbor. That was just the way he was. He would feel he could get food for us.

He was a very proud man, even though he didn’t have any money to buy clothes. He always tried to wear a suit, even if it had patches. I could never figure that out — why he wore a suit and a tie and his clothes all patched up. He always wore a gun, that’s for sure!

I remember the time they tried to kill Dad. Of course, Junior probably don’t remember; he was only 2 ½ years old at the time. Dad came rushing into the house one night about eleven o’clock and woke Mom and me up. He said, “If anyone comes and asks you about what time I got in last night, tell them I got in about seven o’clock.” It was then around eleven. About ten minutes later, we heard guns coming up over the hill — where we lived was called the company farm — and my father got up and went out on the porch. My mother got up and went right out with him, and a kid, being nosy like I was, had to stick my head out the door too. Here’s the militia all up on top of the hill! I don’t know how many. The moon was shining and you could see them up over the hill. I heard them say, “Get down buddy, get down.” One of them comes down all by himself, has his rifle in his hand, and asked my father what time he got home. He said, “Around seven o’clock.” And my mother said the same thing. So what had took place before that, I don’t know.

My mom was right in there with my father as far as the union was concerned. Let’s say if someone called them a name back then — they called them “punkin rollers;” they used that phrase — my mom was right in there busting them in the nose. One time she walked in the store and this woman called her a punkin roller and my mom hit her. That was just the way it was; she was right in there with my father. Another time one of the company men came up and told us to move. I remember that because it scared me to death. She was peeling apples with one of my father’s long, switchblade knives, and he told us we had three days to move. My mama shook that knife in his face and said,“We won’t move; we won’t do nothing.” And he took off.

One time, me and my mom was working a jigsaw puzzle on the end of the table and Dad had a high-powered rifle and an automatic shotgun laying in the middle of the table — you know how that is whenever there is a strike. My sister Birtha was looking into the high-powered rifle, and she just stepped over to the side. I was a child that loved guns, because my father had taught me to shoot, and I just put my finger in the trigger and pulled it and it went off. Birtha had just stepped aside. It went right through the walls through a big oak tree....

The day my father was buried, he had a place on his eye where the militia tried to run him over with one of those motor cars. He was walking across the trestle on his way to Wilder and when he saw the car coming, he fell down through the bridge and swung from the trestle till the car got by. Then he climbed down all the way — I don’t know how high the trestle was — and walked around the other way.

After they shot him, they busted their gun handles over his head. He was shot eleven times. My husband was at the church when it happened. They were having some kind of meeting, a revival or something. He went right down afterwards, and he said they (the thugs) was out on top of the store with a machine gun and the others were all around. I guess they wanted to help, but they knew it wouldn’t work.

There was a lot of commotion down there after he died because everybody was afraid. There were people riding up and down the street. I know that we moved right immediately out of the company house; we had to. We moved into Highland. I think the house had three rooms. I don’t even remember who moved us, to be honest, or how we got there. But I know the ones that was for the company would ride with their guns out. They were trying to run off the union; they were afraid the union was really going to start firing.

As far as I can remember, my father was always for the men.

Barney: When I was growing up there, people sort of expected me to be like my father. That was one reason I was kind of glad to get away from there. I was brought up by a different man altogether, Jess Smith, and he had a different personality. He thought you would be better off to take a little something than to rush into anything and get in trouble or hurt somebody. I was more like him, in a way, than I was my dad. Although I had a certain amount of my dad’s temper, and a few times that got me into trouble. I took after my dad when it come to watching somebody push somebody. I never did like to see somebody pushed, especially the underdog. I took after him on that. But Jess, the one that raised me, he was one of the best men I ever knew. There is hardly anyone that would take a kid and treat him like his own and take his last two dollars and go buy him a pair of shoes.

They are all good people down in there. There was some that scabbed. Well, I never did have hard feelings toward them cause they was just trying to get something to eat. You could hardly blame them. They were caught between a rock and a hard place. It was rough.

They all felt pretty strong about Dad’s death. I was sitting up there in Monterey one day in front of the barber shop, and this guy came up and started talking to me. He was from Wilder. He asked me who I was, and I told him. He said, “I knew Barney well,” and he told me where he lived. He said, “I’ve got guns at home; I’ve got rifles and everything. If you ever take a notion that you want to settle that debt, you come down and you can use my guns, and if you want me to, I’ll go with you.” That’s how strong some of the people felt about it. Course I may have felt different about it if I had remembered Dad, but I didn’t remember him.

I don’t have anything against unions, but I guess I look at it differently than what my father did. He was buried on my sister’s birthday which was the second of May. On the sixth of May, I was three years old. So, from the time I was born it seems like everytime I get mixed up with a union that somebody sets their foot on me one way or another. I lost him. So naturally I didn’t get any education in that part of the country.

About 19-and-48 they started organizing the mines out at Monterey, Tennessee, and that is where my brother-in-law, Jess, worked. There was about 200 and something people worked there in this big mine. Well, when they finally got the contract settled, there was only about 75 people that went back to work. The rest of them was out.

Course I realize that unions are essential. Labor would be nothing but slavery without unions; that’s the reason they organized to begin with. Like them miners — back before they organized, them guys would come up owing the company at the end of the week. Instead of drawing a check they would owe the company. They would come out in what they called the red because the company owned the house they lived in, owned the store they traded at, and owned the people. The unions changed that. We’ve got to have unions. But they are kinda like the government; there’s a lot of things they could change and it would make them a heck of a lot better.

I think what soured me more than anything else was the fact that after my dad was killed and buried, the union didn’t bother to come around and find out if his family was still alive or whether they were starving to death, which we came pretty close to. My mother was sick all the time and even if there had been any work, she couldn’t have worked, because she would take a spell and fall wherever she was.

I didn’t go to school except once in a while. My sister did; she went to school a little bit, but someone had to be with mama. When I was about seven years old, I was setting on the back porch and my mama took one of those spells. She was fixing dinner and fell on the stove. Someone had been there with a small baby and there was this chair across the door to keep the baby from crawling out. I remember I cleared that chair and pulled her off the stove and laid her on the floor. Then I went to Twin to get some help.

Everytime she would take one of those spells, she would always holler, just let out a scream-like. It was for years after I got away from her that I could hear something that sounded like that scream and I would be on my feet. I never did get over it completely. To me she died a thousand times, because I could see her hitting her head on something. I wanted to run the other way, but I always run toward her.

Della: I got married when I was thirteen. My father died when I was twelve, and the next year I married my husband. When I was fourteen, I had my first child, and when I was sixteen, I had my second one. We lived together — never separated or anything — for 35 years. He was killed in ’69. All that time that he lived, he worked in the coal mines — only when he was on strike or circumstances would come up and they would lay him off - up until the early part of ’51. Then we moved north.

He was 23 when we married. We lived together for two weeks, and then my mother and my brother and sister moved in with us. They stayed with us off and on. Mom would get her own place once in a while and then they would move back, or we would move in with her. I could not stand to think that my mother and brother and sister was alone. I was only a kid, actually a kid, and to think that they were alone, or I was eating and they wasn’t — that I couldn’t take.

My husband Jess worked in the Fentress County Coal mines at Twin. He worked there from the time he was sixteen years old. He went to work with his father in the mines loading coal, and he did every kind of work in the coal mine that can be imagined. I don’t know whether he ever run a loader or not, but I know he did all the rest. He coupled. He loaded coal. And he shot down coal. He was all the time in the union. He was in the union when my father died. He was at my father’s funeral.

See, when they came out at Twin, my husband was working there then, and he knew my father well and liked him very much. Course I didn’t know him at that time cause I was only a child.

He was one of the strikers at the Twin mine. Met with all of them at the meetings, and I’ve heard him tell tales about my father, and how he would organize them and they would meet in the woods.

I think one reason I got married was because I wanted a home, someone to be with me and my mother and brother and sister. I was scared to death, and 1 thought it was better to be married to someone than it would be for us to be alone all the time. It worked out good, except it’s a wonder it had.

Naturally when I think back on it now, it really makes me bitter to think that my mother is in a nursing home and he’s gone. And what’s the union done for us. I mean, really, what have they done? Not one thing!

OHIO

Barney: I worked from the time I was about fifteen. I got a job at a sawmill right below the house. They only worked one day a week, and I was making fifty cents an hour. Then I got a job at a hardwood flooring company. I still only made fifty cents an hour, but I got to work five days a week. I had to lie about my age, had to tell them I was eighteen. I went to work in a coal mine when I was seventeen with my brother-in-law. Then I left Tennessee and came to Ohio.

I came by myself, but my sister and her husband were already up here. My brother-in-law, Junior Bradford, got me on at NCR. He worked there. That was before they was so strict about education. I was lucky to get in. Altogether I didn’t go to school two years in my life. I just made it on my own, the best way I knew how.

It was quite an adjustment moving north — from the coal mining camps to the city. I still haven’t adjusted. I still got my ways which is different to people in the city. I lived with my sister Birtha and her husband that first year. Florence and I got married in ’52, the 19th of April, 1952. She’s a Buckeye. She’s a Yankee! We get along pretty good. That part I would do over again. If I could leave anything out, I wouldn’t leave that part out.

I would go down to Tennessee on the average of about once every two or three months, but I didn’t run down every weekend; it was too far. At that time I wasn’t making much money. But every chance I got, I would go down to Wilder and Twin. I liked those people out there and they liked me.

I found quite a bit of prejudice in the shop itself. I worked there for 24 years, see, and there was these kids that would come in — maybe that wasn’t that old. Even though I was working there before they was born, they was wondering why somebody from the South was up here taking their job. That thought run through their mind.

I had a good job at NCR. That was the best place to work in the state of Ohio whenever I went to work there. Notice I said was the best place. Over a period of time it got pretty rotten.

When I went to work there, the foremen were just like the men. They would come around and talk to you, work with you, find out how you did your job. We did good work. Then they started a foreman’s school. Someone from high up got this idea to send these guys to school and to teach them not to associate with the workers. So, the first thing you know, this conflict comes up between management and labor. I could feel it, you know, I could see it coming, but there wasn’t anything I could do about it. I couldn’t tell the president of the company he was making a mistake.

Anyone could go to the foreman’s school. They wanted you to sign up for it. Some of the guys that I worked with went. They were the ones that told me how it operated. I didn’t sign up because I knew I didn’t have the ability to be a foreman without an education. I can do a job with my hands, or with my head, for that matter. I can figure, but when it comes to writing stuff down, I am out. And I know I didn’t have the ability to be foreman, although I do have the ability to handle men, because I treat them like myself. I treat them just like I would want to be treated. You can’t push men into doing this or doing that, and get a good job out of them.

After a time the foremen really started pushing. It seemed like they were trying to prove that they were the bosses. In other words, I’m the boss and I want you to know it, buddy. That was the attitude they had. The men didn’t like it, so naturally when this union wanted to get in, they got in. But they couldn’t have got in ten years before that. There was no way they could have gotten in, because we had everything that the unions were giving. Whatever contract that Frigidaire got, NCR would come up and meet it and maybe a little better. We had a beautiful place to work until somebody fouled it up.

I worked in what is called the heat treating department, and I also did some welding. I wasn’t a certified welder, but I would go back and work with someone who was certified. We treated the metal. There are certain working parts that go into cash registers and adding machines that have to be drilled, and the metal has to be soft so they can drill a hole in it. Then there is certain places on the metal that has to be hard — like where anything hits it — to keep it from wearing. We did all that.

When I first went to work there, I started off at $1.05 an hour. I was making about $6 an hour when the union came in. Naturally when the union came the company did everything they could to make the union look bad. Like if you were working on a job that paid $6 an hour, they would move you off that job and bump you down to one that paid $4. Then they cut the job down that you were on, so even if you went back on that same job, you would go back at a lower rate than you was making when they took you off. They also had these jobs that they called “non-interchangeables.” I was laid off after 24 ½ years, but they still got guys working there with only 18 years seniority, because they were working on these non-interchangeable jobs. If they had more seniority they could bump you, but you couldn’t bump them. In other words, it was a set-up so that the company could hold the ones they wanted and get rid of the ones they didn’t want.

One reason I went for the union is because I figured that it was a large organization, and if we are going to have to fight the company, we are going to have to have something to fight with. I figured that when they negotiated a contract the union lawyers would come in and negotiate with the company lawyers. Well, where I think they fell down was, they didn’t. They elected officials out of the shop, laymen like myself that worked out on the floor, and expected them to negotiate a contract with company lawyers.

That is how they got in these noninterchangeable jobs and all of that stuff. They come up with about the silliest thing I ever heard of, what they called a “cap” on the cost of living. You see, we had a cost of living that was supposed to go up when the cost of living went up. In this contract they signed, they put what they called a cap on it. In other words, it stopped where it was at. When I got laid off, we were about 61 cents behind on the cost of living, which would have amounted to about $ 12,000 to $ 15,000 in our pockets during the time of the contract.

It wasn’t long after I helped organize the union that I realized it wasn’t doing what it should. Anyone that worked at NCR and worked under the union looked down on it. At least with the independent union we could go in and discuss things with the foremen, and they were on our side too. But with the big union, it got to where you couldn’t hardly get a representative to go into the office with you. I think they thought that if one person had a beef or was getting walked on, he was only one vote, and he didn’t matter enough to go into a lot of trouble. The only way that you could get anything done was if the whole group was getting walked on. Then they could go in and the union would try to do something because there was a lot of voice there. Now the company got this too, and the company split these groups.

That’s the reason the company set up these different jobs. They would set up a job over here and would have five or six men in a group. Then they would have another job over here with five or six men that would be another group. Now the first group would get walked on. They could cut the job or do whatever they wanted to do. The second group wouldn’t say anything because it wasn’t them that was getting hurt. That was real smart on the company’s part. Then once they got it settled and the men quieted down — took the cut or whatever it was they was getting - they could turn- around and work on the other group. The first group would say, “Well, they did it to us and you guys didn’t say nothing, why should we do anything?” They used psychology. They split them up.

The work at NCR was hard to take and it didn’t get any easier. The longer I was there, seemed like the worse it got. It got monotonous; got real hard to take. I just got bored with the whole thing. And the work did change, especially the relationship between the workers and management, and that didn’t help any. Before they started pushing so hard, there was time to talk to each other. But after they started pushing, they brought in a work system that some college professor had worked out at the University of Dayton, to figure out how to get more work out of the men.

This was before the union came in. They would stand and time us out like they do on any piece work job. They had it figured right down to the second as to how long it took us to run so many pieces. They started us off in piece work at a reasonable price. Then they kept cutting the jobs until they got it down to where we were not making as much money as we were at the standard rate. They have you working twice as hard and making very little more money, if any. Besides it is real nerve-wracking. I hated piece work. I would have gone back on my old job for 50 cents less on the hour.

I worked there for 24 years and three months. When they laid me off, they said there was no possiblity of ever getting called back. I have five years of seniority rights - five years of recall rights. I was a member of the union for six months after I got laid off. That time was up in September of ’75 and I lost all my union benefits. And you know, even though you have the abilities to do a job as good as the next man, whenever you go into make out an application and you put down you are 45 years old, and you don’t have any education ...well, forget it. So it kind of makes it a little rough.

FOOTNOTES

1. Two other songs helped popularize the Davidson-Wilder strike, “Little David Blues” by Tom Lowry and “Davidson-Wilder Blues” by Ed Davis. Like Della Mae, Tom Lowry did not know that his song had been published until he was interviewed by Florence Reece, (who wrote “Which Side Are You On”) Brenda Bell and Fran Ansley. (The interview with Lowry also appeared in Southern Exposure, Vol. 1, No. 3-4.) When we talked with Della Mae last year she knew only that her song had been published in books; she did not know that it had been recorded by Hedy West (Old Times and Hard Times, Folk-Legacy Records) and by Pete Seeger (Industrial Ballads, Folkways).

2. The meeting was the Continental Congress for Economic Reconstruction. Howard Kester was one of the many “outsiders” to offer help to the striking miners. He was at that time working with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, but parted ways with the FOR because he defended the right of the miners to take up arms in self-defense. Dr. Alvah Taylor of Vanderbilt University Divinity School, Myles Horton of Highlander Folk School, and Don West also gave active support to the strike. Kester, speaking at Graham’s funeral said, “I had no better friend. I loved him as a brother, not alone for his own worth, but for his place in the leadership of America’s toiling millions.”

Tags

Fran Ansley

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)