This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

The joke in Alabama used to be that if Attorney General Bill Baxley wanted to run for governor, he had to get married first. And if he wanted to run and win, he had to marry Lee Wallace, George and Lurleen Wallace’s youngest daughter.

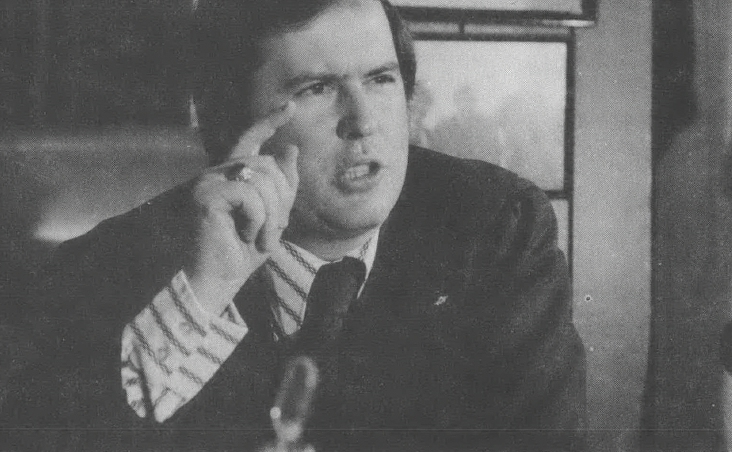

Baxley, a bold, flamboyant figure who became the state’s chief law enforcement officer when he was twenty-eight, had long been considered Alabama’s most eligible bachelor.

By this time next year, the long-familiar visage of George Corley Wallace will be gone from the Alabama statehouse. And, at age thirty-six, William J. Baxley is married — though not to Lee Wallace — and already on the campaign trail to succeed George Wallace as governor. If he can overcome recent widespread rumors and allegations about his financial dealings, he just may win.

Baxley is something of an enigma. He makes noises in the best populist tradition against the same “big mules’’ on which former governor “Big Jim” Folsom threatened to use his corn shuck mop as far back as 1946. Folsom, a giant of a man reminiscent in some ways of Louisiana’s Huey Long, was a racial moderate who assailed “the interests.” He attacked the Alabama Farm Bureau for its manipulation of state politics, but never had much success at it.

Two decades later, Baxley hauled the Farm Bureau and five other powerful lobbies into court for violation of election laws. He won the case, though the conviction was overturned by a higher court. Baxley then sued Edward Lowder, a Farm Bureau official reported to be one of the most powerful men in the state, for using the Bureau’s vast financial resources to benefit his own business interests. The suit continues, though Baxley’s chances for ultimate success are uncertain.

Baxley’s prosecutions of politicians, church bombers, corporate polluters and inmate murderers have earned him, on separate occasions, praise from both Birmingham liberals and Wiregrass rednecks. His energetic activity has won respect in a state where two previous attorneys general left office under criminal indictment and a third is remembered chiefly for his odd habit of accosting people on the street for such breaches of the peace as jaywalking.

Baxley is riding high now, following the conviction of Robert Chambliss, the ex-Klansman found guilty in November of the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. The story is tragically familiar; everyone knows it, knows that four little black girls died in the explosion and that the murderers were never caught.

Never caught, that is, until Baxley came along. His pursuit of the men who planted that dynamite has been relentless, almost fanatical. According to Baxley, he was in his third year of law school at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa when the bombing occurred; he was so shaken by the event that he hardly slept or ate for two days, and when he took office as attorney general seven years later, he put the unsolved church bombing at the very top of his agenda.

That story sounds almost too good to be true, almost certainly the product of some press office flack, except that Baxley’s friends and many reporters who regularly cover him believe it happened just that way. They also say the incident clearly demonstrates the generational difference between Baxley and Wallace. Baxley thinks that, if anything, his prosecution of Chambliss will hurt him in the upcoming campaign. He told a recent gathering of Montgomery press people that the Chambliss prosecution won him support in New York and California. “Unfortunately, the people in New York and California don’t vote in Alabama,” he said. But Bill Baxley does not seem to care if he loses the votes of some of those who resent the resurrection, after all these years, of the spectre of the bombings and beatings so closely identified with Alabama during the Civil Rights era.

Going after Chambliss is the kind of bold stroke that has characterized Baxley’s personal life style and career. He is impetuous and likes ton gamble. His friends say he is bold to the point of recklessness, but pragmatic to the point of ruthlessness. Several years ago, he made headlines with a Las Vegas trip in which he won $30,000. Though such exploits draw heavy criticism in the media, Baxley has shown no inclination to alter his habits.

In person, Baxley is disarmingly charming, in an innocent, boyish way. His best friends are two former Montgomery newspaper journalists with whom he once shared a bachelor apartment. Friends say he hates to be left alone, and that he has the fear some politicians have of being killed: he has been known to literally barricade himself inside his apartment, sitting with a gun nearby and furniture against the doors, watching television. He is also morbidly afraid of dogs, and will cross the street to avoid meeting certain breeds on the sidewalk.

For a politician, he seems somewhat aloof. He has a reputation for not returning phone calls and for ignoring the buddy system that other politicians follow. As a result, he is said to have few real friends in the Alabama Legislature, and that could be problematic if he were to win the governor’s office.

Baxley has also been known to prosecute some of his own allies, as Kenneth “Bozo” Hammond discovered, much to his discomfort. Hammond, a shoe store owner from a small Alabama town, had been elected president of the Alabama Public Service Commission (PSC) largely on Baxley’s support. Baxley had campaigned hard for him because he opposed the incumbent president, Eugene “Bull” Connor. Bull Connor had parlayed his notoriously racist practices as Birmingham’s public safety commissioner during the civil rights movement into the lucrative position on the PSC, and Baxley was anxious to see him finally defeated. With Baxley’s active support and advice, Hammond won. But several years later, Baxley prosecuted and convicted him for using his influence with the utilities to get bribes from suppliers. A reporter who covered Hammond’s trial said it was almost like watching a father and son: “Now, Kenneth, tell me . . . ,” Baxley would say while Hammond was on the stand.

Baxley also once resisted overtures by no less a legend than Paul “Bear” Bryant, the Alabama football coach. Baxley had entered a Birmingham restaurant and spotted Bryant sitting alone, obviously immersed in one of his occasional bouts of melancholy. Baxley is a great fan of Bryant, and he waved him over to have dinner. After a time the conversation turned to the problems Baxley’s office was causing some of Bryant’s strip miner friends.

Baxley pointed out that the cases were handled by Asst. Atty. Gen. Hank Caddell, whose father is on the University of Alabama Board of Trustees. “Yeah, Henry Caddell is an old friend of mine and a good man, but his boy is just trying to be a turd about this,” Bryant drawled. It was, again, a case of one generation running head on with another, and though Baxley politely heard Bryant out, he never called Caddell off the strip miners.

Caddell, like several others on Baxley’s staff, is an Alabama boy who went off to Harvard Law School. When Baxley took office, he recruited Caddell and several others and brought them back home. He also put black attorneys on his staff, and that had never before happened in Alabama. Baxley has given his assistants considerable freedom to operate, even on those occasions when it seemed to go against his best political interests. Baxley is pro-labor, but he risked the jobs of thousands of Birmingham steelworkers while Caddell wrestled with United States Steel Corporation about the air pollution caused by its furnaces. The company had been given four years to clean up its pollution, and faced stiff fines for its inaction. But US Steel said they would close the plants down rather than pay fines, and for a time it looked as if that would happen. Six hours before the final deadline, the company backed down and agreed to pay the fine for every day they were in violation. Today, air pollution is greatly reduced in Birmingham.

Caddell and Baxley have also attacked the US Army Corps of Engineers, the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Environmental Protection Agency for “acting against the best interests of Alabama.” Baxley’s aggressive action on environmental issues, political corruption and white-collar crime endears him to many progressives and liberals, but other stands delight conservatives. He is, for example, a law and order candidate of the first magnitude and believes sincerely in the death penalty as a deterrent to rising crime. In his first statewide race, he campaigned for attorney general by saying that, as the Houston County district attorney, he had obtained the most convictions in history.

Since Wallace’s first term, Alabama has not executed anyone; but there are more than twenty condemned men in Holman Prison now. A reporter asked Baxley recently if he would commute any death sentences and Baxley replied that he was personally familiar with the cases of twelve of the condemned and that they deserved to die. An effective courtroom lawyer with an old-style bombastic delivery, Baxley himself handled the prosecution of Johnny Harris, a black convict sentenced to death for killing a guard during a prison riot several years ago. Alabama now has a new death penalty law, but there wasn’t one on the books at the time of the riot. Baxley found a hundred-year-old law which allowed death for a prisoner under life sentence who commits murder. Since Harris was the only inmate in the riot who fit that description, Baxley prosecuted him for the guard’s death, though many other prisoners were involved.

Morris Dees, who was Harris’ lawyer, says, “In his closing argument, he whipped up the jury, shouting so loud the windows rattled. ‘If I’d a been there,’ he’s yelling, ‘I would’a set me up a .50 caliber machine gun in the door, and I would’a given them one minute to get out, and anybody that wasn’t out, I’d a mowed them down. Killed them all.’”

There are lawyers in Alabama who will forgive whatever sins Baxley may have committed, but will neither forget nor forgive what Baxley did to Aubrey Cates. Until the last election, Cates was the presiding judge of the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals. He had been on the bench for two decades and was considered one of the finest legal minds in the state and was the only Rhodes Scholar ever to serve on that court. Baxley accused Cates of “legal nit-picking” and of having a judicial philosophy of setting criminals free.

Baxley recruited one of his assistants, twenty-eight-year-old Bill Bowen, to run against Cates and, in a state-wide television blitz paid for from his own pocket, Baxley attacked Cates, citing two examples of reversals he found particularly distasteful. Neither of the opinions had been written by Cates, and Baxley carefully neglected to say that no judge could reverse a case without majority agreement. Wade Baxley, the attorney general’s brother who practices law in Dothan, was among those attorneys who defended and supported Cates, but the damage had been done.

Bowen won easily, demonstrating that Alabama voters still respond to skillful demagoguery and that Bill Baxley is a man to be reckoned with in a statewide campaign. Still, Baxley’s effective ouster of a judge with whom he disagreed was viewed by many with alarm. “What he did to Aubrey Cates is exactly the same thing the John Birch Society would have done to Earl Warren if it could have,” said Ray Jenkins, editorial page editor of the Montgomery Advertiser. Cates became ill and died not long after leaving office. Baxley said after the election that he had made a political mistake and would not repeat it. Still, the incident will haunt him during the campaign.

Baxley’s financial dealings may cause him even greater trouble. His statements show that he has been speculating, often putting as much as $20,000 into a particular stock, but holding it for as little as a week before selling. “He has a high-risk life style and this is part of it. We don’t know yet all the details of his gambling and his debts,” says Mark McIntyre, an investigative reporter for the evening Alabama Journal in Montgomery.

In recent months, McIntyre has been probing Baxley’s relationship with a Louisiana millionaire named Louis Roussel, who controls a number of insurance companies which operate in Alabama. McIntyre calls Roussel’s American Benefit company “a vast, self-dealing web,” and says that of the company’s stock portfolio in 1976, ninety-eight percent was invested in other Roussel companies. The investments paid a cumulative dividend that year of 0.17 percent, and Roussel loaned himself $4 million of the American Benefit assets, at three percent interest. Roussel is currently suing McIntyre for his coverage of Roussel’s finances.

Roussel says he delivered $25,000 in cash to Baxley’s campaign in 1974, when Baxley was running unopposed. Baxley says he returned all but $1,000, and he filed a campaign contribution statement for that amount. Roussel has promised an additional $100,000 when Baxley runs for governor, and Roussel’s New Orleans bank has given Baxley a personal loan of $55,000.

Recently Baxley went to Oklahoma City to testify as a character witness for Roussel in an insurance investigation there. McIntyre says that only Baxley knows why or to what extent he is involved with Roussel. Baxley’s associates say that the attorney general is broke and is trying to sell land he owns near his home in Dothan, but Baxley himself now responds to McIntyre’s questions with insults instead of answers. McIntyre believes Baxley is honest. “He won’t tell you the whole story, maybe, but to the degree to which he will talk, he’s pretty reliable.”

Baxley’s profane insults to those who are bothering him are not new. When an official of the white supremacist National States Rights Party wrote Baxley two years ago protesting his reopening of the church bombing investigation, Baxley sent back, on his official stationery, a one-sentence reply: “My response is — kiss my ass.”

Most of those who know Baxley feel that he would be a good governor — pragmatic, autocratic, perhaps, but energetic and activist in areas long neglected by George Wallace. He is considered likely to push for a repeal of the right-to-work law, to work for more equitable taxes and to try to shake off the grip that lobbies still hold on state government. If elected, he has promised to “twist a lot of arms and kick a lot of ass,” and so would probably be a one-term governor. And that, Baxley says, would be all right with him.

Tags

Randall Williams

Randall Williams is a fugitive staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. He is currently living and working in north Georgia, where he is guiding the start-up of two weekly newspapers, the Chickamauga Journal and the Lafayette Gazette. (1980)

Randall Williams is an Alabama native, a journalist and former editor of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s newsletter. He is now on the staff of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1978)