This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 2, "Just Schools: A Special Report Commemorating the 25th Anniversary of the Brown Decision." Find more from that issue here.

Daily across the South, new stratagems are being added to the melancholy list of dodges, evasions, sleight-of-hand tricks and massive resistance used over the years to keep blacks out of college. The defiant politician of the '60s, standing in the university doorway, refusing entrance to one or two carefully chosen students, is gone. His place has been taken by faceless administrators in every Southern state who, in the name of equality and Supreme Court doctrine, set forth policies which quietly, but effectively, prevent hundreds, not handfuls, from going to college.

On the surface, many if not all the policies appear uniform, just and free of bias with regard to race, class or sex. They win quick acceptance from legislators and university governing boards by promising administrative effectiveness while ensuring the continuing flow of federal dollars. The particular victims of these ministrations, however, are the 35 historically black public colleges and universities, enrolling about 118,500 students.

Flowing from the great headquarter citadels for the South's increasingly centralized university and college network - Chapel Hill, Richmond, Knoxville, Columbia, Athens - are policies on enrollment ceilings for out-of-state students, program allocation, admission and graduation criteria, tuition levels, budget formulas, student aid disbursement, and dozens of lesser institutional housekeeping functions seldom heard of but critically important to the maintenance of publicly supported higher education. Many of these policies are already in place. Others are being considered. And they have taken a toll:

In less than a decade, enrollment at the traditionally black, tax-funded schools has dropped seven percent. Between 19 76 and 1977, over 1,500 fewer students signed up at these 35 colleges. Some schools face loss of identity. For instance, West Virginia State College, once the only school open to blacks in that mountain state, now enrolls a predominantly white student body. Oklahoma's Langston University, mired for years in restrictions similar to those placed on most black schools, has been led by four presidents in three years and may be closed by the very legislature which has kept it poor.

Few educators in these black public institutions have been able to protest the new policies. "We are in the position of the colonial administrators left behind by the British to run India when they pulled out," one said after receiving assurances of anonymity. "They have given us broken institutions, a little money, and said, 'You're on your own.' If we say a word against this, we're fired."

Now, however, through the National Association for Equal Opportunity in Higher Education (NAFEO), their voices are being heard on Capitol Hill. They have questioned why not a dime of HUD money recently allocated for new construction in higher education reached a single black campus. NAFEO has also filed briefs as part of a landmark 1973 case, Adams v. Richardson,* which requires the Department of Health, Education and Welfare to stop dragging its feet in pushing desegregation in higher education. NAFEO presented the theory supporting the continued importance of black colleges:

We have recommended that the cornerstone of the state (desegregation] plans should be to protect, enhance, and expand the historically Black colleges and universities as the most effective way of expanding the pool of educated Blacks ... It would be a mistake to assume that Black Americans have reached equality with white Americans and that the same . approaches would be equally beneficial to members of both groups . ... In short, because of the essence of inequity and because the state has been so heavily implicated in this inequity, special efforts are required by the state to ensure that compensatory measures are taken to move more rapidly toward equality ... The primary purpose of strengthening the Black colleges should be to enable them to do a better job of their primary mission of educating more Blacks . ... A second and most vital function is the preservation and study of Afro-American cultural heritage . ... Still a third function they serve is providing for the Black community social pride, a sense of positive identity and accomplishment of leadership. This is a wholly constructive function in a society which is culturally diverse.

Specifically, NAFEO urged that five steps be taken to build up black institutions: financial support which allows for remedial education; capital outlays for new buildings; new academic programs; special faculty and staff development programs; and no mandated "numbers or quotas of white administrators, faculty or students in these institutions as long as they are in keeping with the law and protective of the rights of all American citizens who wish to apply to them."

Existing state policies run counter to all five steps suggested by NAFEO. Late in 1977, Dr. Samuel L. Myers, executive director of NAFEO, formed a four-member team to visit 13 public and 12 private historically black campuses in nine states—Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. His survey of impediments to desegregation policy, the first of its kind, was issued in 1978.

Based on the Myers report, and my own findings in a six-month tour through the South for the Instititute for Southern Studies, it is fair to conclude that even the most open-minded white Southern university administrator seldom, if ever, takes into account the historic deprivations individual black students generally bring to college, or which have marked the life of 130 institutions deliberately ignored and under-financed over the years. Some black administrators in these colleges feel that lack of information, rather than racism, is the problem. Others, however, feel these bureaucrats begin their policy formulations with the goal of undermining or eliminating black colleges. Myers spoke with many educational leaders who "perceive that the officials, working backward, then devise a series of policies which, if rigidly adhered to, would cause the black college to self-destruct .... The statement, 'They are out to do us in,' was articulated too often by too many respondents to be ignored."

Specifically, what are some of these policies, and how do they affect future educational options for Southern blacks?

Admission policy and its implementation is central to the life of any university. Test scores and tuition costs are key elements in those policies. Across the South, new criteria for admissions are being set in place. In the name of assuring minimum proficiency levels, administrators are upping the requirements on scores of standardized tests used in the admissions process. At Elizabeth City State University, one of North Carolina's five traditionally black institutions, officials are being asked by the consolidated university administrators to raise the minimum Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) score necessary for entrance by over 20 percent. The school, like others faced with similar "improvements," would be hit by two licks with one policy:

First, many students who might choose Elizabeth City State would be denied admission. Second, the university, like the majority of black colleges, has designed its teaching-learning program to fit the students' abilities, not predetermined standards of "academic excellence." Remedial education has been a central part of Elizabeth City State's historic and current mission. By denying the students access to the college, or to any institution which accepts students with low tes· scores, the state simultaneously reduces the potential number of black graduates and cuts into the school's vita and traditional role.

Despite widespread talk among Southern policymakers about prohibiting remedial education at four-year colleges - such as Elizabeth City State - and relegating the function to the community college system, no state has yet taken this step. Meanwhile there are indirect restrictions. For instance, the Full Time Equivalency (FTE) budgeting formulas used b~ many Southern states to allocate funds generally do not include money for remedial education. "Indeed," as Myers noted in his report, "if classes are kept small to make possible more effective learning on the part of the students with academic deficiencies, the formula budget, if based on FTE, actually penalizes the colleges. In one state, if classes fall below ten students, the college is permitted to hold the classes; however, no funds whatever are provided." This policy also discourages, if not prohibits, the inception of new programs in which enrollment initially could be small.

Other states proclaim their determination to support remediation programs, but then fail to finance them. Georgia, for example, decided in 1976 to curb unusually high dropout rates at the state's three historically black schools - Albany State, Fort Valley State and Savannah State. Policymakers decreed that tutorial programs and academic, personal and vocational counseling should be available at each institution. July 1, 1978, was set as a date for implementation. All of these advances were given extensive press coverage. But when the policymakers submitted their budget, no funds were requested to implement the plans. By mid-1979, the three schools which once served all Georgia's black students, enrolled less than one-third of the blacks in Georgia colleges. Black educators I spoke with declared their certainty that Georgia's white administrators were shutting down the schools. They pointed to the fate of all-black, “separate-but-equal” high schools after integration. "They still take integration mean a one-way street," one black teacher told me. "We ride on their side of the street, or we walk."

State policies are being developed that strike at enrollments in another way. Approximately 23 percent of the students at the 35 historically black institutions in the U.S. are classified as nonresidents of the state in which they attend college. The vast majority of these public colleges are in the South, but they draw students from all across the nation. Moreover, because many graduates moved north or west for better paying jobs, the alumni are nationally distributed. But it is becoming increasingly difficult for the children of these alumni to attend their parents' alma mater. Most states already have disproportionately high tuitions for out-of-state students; others are now adopting strict limits on nonresident enrollment. Alcorn State University in Mississippi, for instance, charges in-state students $588 tuition. For out-of-state students the fee is $2,138. As Myers noted, "To cut off, artificially, out-of-state enrollment is to cut off the historically black college from its alumni, supporters, and its heritage. White colleges, on the other hand, are more locally oriented. Therefore, an equal out-of-state enrollment restriction has a greater adverse impact on the black college than on the predominantly white institution."

Budgets are used in dozens of ways to hinder black schools. Ostensibly, funds for building repair are dispersed equally among all state colleges based on enrollment. But most black institutions operate out of buildings that, once erected, were usually forgotten. Upkeep is so great today, some administrators argue, that expenses should be considered capital improvements rather than operating appropriations. Beyond the question of what to call a budget line item, the funding formulas do not take into account the disproportionate flow of operating funds into the predominantly white institutions from endowed chairs, accumulated foundation resources and endowments. "This, in itself," one economics professor told me, "perpetuates an inequity in the context of equality."

Black colleges have been further attacked because their budgets seem to require unusually high per pupil expenditures. The cost differential is real at many of these schools. The educaf1onal needs they are trying to fill are usually greater than at comparable predominantly white institutions. On the other hand, the higher costs are often misleading. In at least one instance, the state insists that all student aid be included in the college's budget. This figure is then divided by enrollment to get a cost per student. Since 90 percent of this school's student body receives aid, the figure is at first glance high. And it looks worse beside a predominantly white institution with 23 percent of its students on student aid. State officials have publicized the difference to infer that black-run schools are inefficient.

Policies affecting student aid distribution are even more crucial to the future of education for blacks. The National Center for Education Statistics completed in 1978 a follow-up study on the 1972 high school graduating class. Chief among their findings was that financial aid apparently is a strong incentive for students to stay in college. Dropout rates were lower and graduation levels higher for students of all races, income and ability levels if they received aid, either as loans or in the form of campus jobs. Nearly 70 percent of all black college freshmen received aid in some form. And Dr. Johnny R. Hill, executive director of the Office for Advancement of Public Negro Colleges, estimates that 75 percent of all currently enrolled black students receive financial aid. The average parental income of these students is just over $6,000 annually.

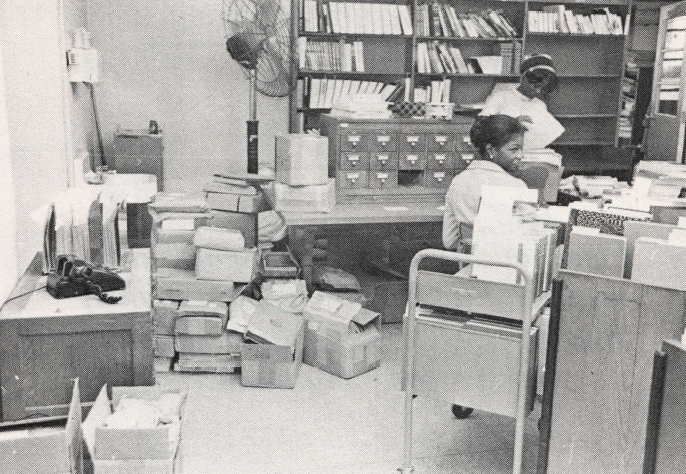

Ironically, while financial aid apparently helps the student make it through school, it may be the undoing of some understaffed colleges. A look at the bureaucracy associated with work-study programs illustrates the impact on a school’s administration, especially on accounting and business personnel. Each student’s Social Security number must be filed along with a complete statement of parental income. Each of these must be independently verified. Time cards have to be made out and maintained for each student. In other words, with large proportions of their students receiving financial aid, some black institutions face the prospect of being choked to death with the paperwork necessary for their students to continue their studies and graduate. Please for computers or additional resources to soften the administrative burden have been ignored. As Myers found,

The computation of the packages to assure that each student receives his maximum allowance and assure that the aggregate of distribution stays within the allocation to the institution, requires human and physical resources that far exceed the three percent administrative costs usually built into the program.

Colleges and universities have complained so loudly about the proliferation of paperwork in recent years that a federal interagency committee is exploring ways to curb the problem. But this paperwork places an additional burden on black schools precisely because so much of it deals with financial aid. Myers also reported “a widespread feeling that the fiscal audits are often used to undermine and harass the predominantly black colleges rather than assessing them for compliance. Young, inexperienced accountants or professional 'hatchetmen' are sent in to uncover as many exceptions as possible. They come more frequently, stay longer, scrutinize more closely, and are generally unsympathetic to the broad social objectives shouldered by the institution .... In addition, the exceptions as publicized in the press embarrass the college officials and further damage the institution's image."

Since the Adams decisions, Southern states have also shown reluctance to provide significant capital improvement funds for black colleges. Virginia, for instance, is under court order to improve the quality of black campuses. But in 1976 the state approved a long-range budget of $86.5 million for construction on public campuses, of which less than $6 million was earmarked for black campuses. The extent to which black college campuses have been allowed to physically deteriorate and therefore require extensive capital outlays was dramatically illustrated by recent appropriations in Florida and Arkansas. In 1976, when the legislature allocated $19 million for traditionally black Florida A&M, $17.6 million was for repairs and remodeling. At Pine Bluff in Arkansas, nearly $400,000 had to be spent to remodel a building for faculty offices and bring an infirmary up to safety specifications.

Similarly, black campuses are being short-changed in the expansion of curricula. Across the South during the 1977-78 academic year, the 35 historically black schools began offering 29 new undergraduate degree programs, and 13 new graduate-level programs. Even a partial listing of the new undergraduate offerings reveals how severely the curricula of many black schools have been limited by previously unabashed racist policy: Alabama A&M is now awarding a degree in psychology; Bowie State got the right to offer degrees in journalism and mass communications; Norfolk State can now award degrees in music; South Carolina State will soon award degrees in social welfare and criminal justice. Nevertheless, policy decisions continue to favor the white campuses. For example, since 1972, the predominantly white and male Board of Governors of the University of North Carolina has authorized the establishment of 85 new degree programs. Only 18 of them, including four on the master’s degree level (in adult and continuing education, agricultural economics, electrical engineering and industrial engineering) went to historically black institutions. And, as of this writing, funding for some of them remains in doubt.

In sum, a slow, determined effort seems underway to eliminate historically black tax-supported colleges and universities. The list of policy impediments could continue: differential salary schedules, default policies on student loans, indirect tuition increases, allocation of federal grants, and other administrative devices used to pinch institutional nerves. Disguised as rational, equitable policies, they continue covertly a pattern of racism just as destructive as the overt neglect of white leaders 20, 40, even 100 years earlier.

Tags

Frank Adams

Frank Adams is author of Unearthing Seeds of Fire: The Idea of Highlander, a teacher and long-time friend of the Institute for Southern Studies. He is writing a biography of Jim Dombrowski. (1982)

Frank Adams interviewed Mrs. McEwin while traveling through the South for the Institute for Southern Studies’ syndicated column, Facing South. (1979)