This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

SNCC—the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—conducted the most important staff meeting in its history during the second week in May, 1966.

There was widespread agreement that it was time for SNCC to begin building independent black political organizations. We were convinced that such organizations working together could end racial oppression once and for all. Most of our time was spent discussing the best ways to publicize and win support for this new approach to the struggle.

We were absolutely convinced that there was no viable future for blacks — poor blacks especially — within the Republican and Democratic parties. We were also convinced that the federal government, where we had looked for support in the past, was part of the problem.

A small minority of those present were worried about SNCC’s new commitment to independent black politics. “How can we create an integrated society if we are building racially segregated political parties?” they asked. This was a legitimate question. Most of us were convinced, however, that it missed the point.

“Blacks are not being lynched and dumped into muddy rivers across the South because they aren’t ‘integrated,’” we countered. “Black babies are not dying of malnutrition because their parents do not own homes in white communities. Black men and women are not being forced to pick cotton for three dollars a day because of segregation. ‘Integration’ has little or no effect on such problems.

“Look at all those ‘integrated’ towns and cities in the Midwest. Niggers up there have it just as bad as we down here. The real issue is power; the power to control the significant events which affect our lives. If we have power, we can keep people from fucking us over. When we are powerless, we have about as much control over our destinies as a piece of dog shit.”

It was obvious that many of those whom we hoped to influence were not thinking in terms of power. We believed they lacked the proper point of view; they did not possess what we called “black consciousness.” Throughout the staff meeting, we talked about black consciousness. It was new and exciting.

What is black consciousness? More than anything else, it is an attitude, a way of seeing the world. Those of us who possessed it were involved in a perpetual search for racial meanings.

Black consciousness, which was an admitted consequence of the failure of the Movement up to that point, forced us to begin the construction of a new, black value system — a value system geared to the unique cultural and political experience of blacks in this country. Black consciousness signaled the end of the use of the word Negro by SNCC’s members. Black consciousness permitted us to relate our struggle to the one being waged by Third World revolutionaries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It helped us understand the imperialistic aspects of domestic racism. It helped us understand that the problems of this nation’s oppressed minorities will not be solved without revolution.

From an organizational point of view, black consciousness presented SNCC with one major problem. More than 25 percent of our members were white. It was obvious that they did not and probably could not possess black consciousness.

During the first month after that meeting, Stanley Wise, Stokely Carmichael (elected SNCC chairperson at the May meeting) and I traveled across the South visiting SNCC projects. Stokely wanted to get a clear idea of the work people were doing. We were in Little Rock, Arkansas, talking with Project Director Ben Greenich and some of his staff when a lawyer came up and told us that James Meredith had been killed.

“Who did it? How did it happen?”

The lawyer didn’t know. He had only heard a news bulletin on the radio. “All I know is that some white fella shot him in the head while he was walking down some Mississippi highway,” he replied.

The news of Meredith’s death reminded me of the dull, aching pain that seemed always to be lurking in the pit of my stomach. Even though I’d always believed that Meredith’s intention to march across Mississippi in order to prove that blacks didn’t have to fear white violence any longer was absurd, I was enraged.

We didn’t find out until two hours later that Meredith had not actually been murdered. The pellets from the shotgun, which had been fired from about 50 feet, had only knocked him unconscious. Although he lost a great deal of blood, doctors in the Memphis hospital where he had been taken were predicting that he would recover. Because we were only a few hours’ drive from Memphis, we decided to go there the next day.

When we arrived at the hospital the next afternoon, Martin Luther King and CORE’S new national director, Floyd McKissick, were visiting Meredith. Stanley, Stokely and I joined them. After saying hello to Meredith and congratulating him on his “good luck,” we left with Dr. King and McKissick. Meredith was still very weak. On the way down, we were informed that although initially reluctant, Meredith had agreed that the march should be continued without him. He intended to join it as soon as he recuperated.

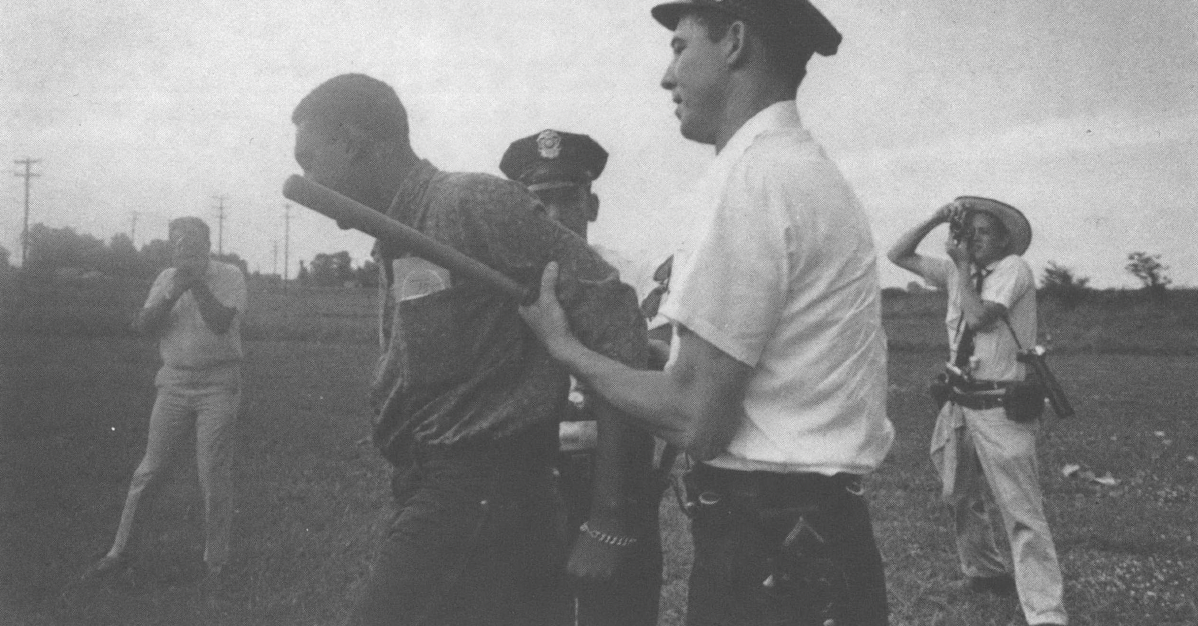

Later that afternoon, a group which included Stokely, Stanley Wise, Dr. King, McKissick and me drove out on the highway to the spot where Meredith had been ambushed. We walked for about three hours. We wanted to advertise that the march would be continued. Although we were all quite tense, there was only one incident. A burly white state trooper, who insisted that we could not walk on the roadway, pushed Stokely. In the ensuing scramble, I was knocked to the ground and nearly trampled by Dr. King, who was attempting to keep Stokely from attacking the trooper.

Two days later, a planning meeting was held at the Centenary Methodist Church, whose pastor was an ex- SNCC member, the Reverend James Lawson. The meeting was attended by representatives from all those groups interested in participating in the march, including Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young, who had flown in earlier in the day.

Participants in the meeting were almost immediately divided by the position taken by Stokely. He argued that the march should be de-emphasize white participation, that it should be used to highlight the need for independent black political units, and that the Deacons for Defense, a black group from Louisiana whose members carried guns, should be permitted to join the march.

Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young were adamantly opposed to Stokely. They wanted to send out a nationwide call to whites; they insisted that the Deacons be excluded and they demanded that we issue a statement proclaiming our allegiance to nonviolence.

Dr. King held the deciding vote. If he had sided with Wilkins and Young, they would have held sway. Fortunately, he didn’t. He attempted to serve as a mediator. Although he favored mass white participation and nonviolence, he was committed to the maintenance of a united front. Most of his time was spent attempting to get the rest of us to agree that unity was necessary. It was obvious to me from the beginning that the possibilities of unity were almost nil.

Despite considerable pressure, Dr. King refused to repudiate Stokely. Wilkins and Young were furious. Realizing that they could not change Stokely’s mind, they packed their briefcases and announced that they didn’t intend to have anything to do with the march. By the time we held the press conference the next day to announce officially that the march would occur, they were on their way back to New York City.

The march began in a small way. We had few people, maybe 150. That was okay. We were headed for SNCC territory and we were calling the shots. We had conducted an all-SNCC meeting with Bob Smith and his staff before the march began and everything was perfectly organized.

A small crew of SNCC organizers had been assigned the task of traveling ahead to make contact in the communities through which we passed. Old SNCC volunteers, people who had worked with us during the summer of 1964, were contacted in each town. They were asked to provide meals, sanitary facilities and sites for the nightly mass meetings. They were also told to make preparations for the voter-registration drives that we intended to conduct in each town.

Although SNCC people were dominating the march, Dr. King was enjoying himself immensely. Each day he was out there marching with the rest of us. His nights were spent in the huge circuslike sleeping tent. For one of the first times in his career as a civil-rights leader, he was 66 shoulder to shoulder with the troops. Most of his assistants, who generally stationed themselves between him and his admirers, were attending an SCLC staff meeting in Atlanta.

Little by little, Dr. King began to agree that it might be necessary to emphasize black consciousness. He also agreed that our commitment to independent black organizations might just work. By the end of the first week, he was giving speeches at the nightly rallies in favor of blacks’ seeking power in those areas where they were in the majority.

From the very beginning of the march, poor blacks along the route were awestruck by Dr. King’s presence. They had heard about him, seen him on television, but had never expected to see him in person. As we trekked deeper into the Delta, the people grew less reserved.

The same incredible scene would occur several times each day. The blacks along the way would line the side of the road, waiting in the broiling sun to see him. As we moved closer, they would edge out onto the pavement, peering under the brims of their starched bonnets and tattered straw hats. As we drew abreast someone would say, “There he is! Martin Luther King!” This would precipitate a rush of 2,000, sometimes as many as 3,000 people. We would have to join arms and form a cordon in order to keep him from being crushed.

It’s difficult to explain exactly what he meant to them. He was a symbol of all their hopes for a better life. By being there and showing that he really cared, he was helping to destroy barriers of fear and insecurity that had been hundreds of years in the making. They trusted him. Most important, he made it possible for them to believe that they could overcome.

As we got closer to the Greenwood area, the nightly meetings took on the character of a speaking fete. Stokely, who had worked out of Greenwood during the summer of 1964, was well known. Many of those who attended the nightly rallies wanted to see and hear him. Others were attracted by Dr. King. The two of them were like dynamite. Their fervent speeches left all who heard them both emotionally exhausted and inspired.

The Deacons for Defense served as our bodyguards. Their job was to keep our people alive. We let them decide the best way to accomplish this. Whenever suspicious whites were observed loitering near the march route, the Deacons would stop them and demand that they state their business. In those areas where there were hills adjacent to the road, they walked the ridges of the hills. We did not permit the news media’s criticism of the Deacons’ guns to upset us. Everyone realized that without them, our lives would have been much less secure.

We had our first major trouble with the police on June 17, in Greenwood. It began when a contingent of state troopers arbitrarily decided that we could not put up our sleeping tent on the grounds of a black high school. When Stokely attempted to put up the tent anyway, he was arrested. Within minutes, word of his arrest had spread all over town. The rally that night, which was held in a city park, attracted almost 3,000 people — five times the usual number.

Stokely, who’d been released from jail just minutes before the rally began, was the last speaker. He was preceded by McKissick, Dr. King and Willie Ricks. Like the rest of us, they were angry about Stokely’s unnecessary arrest. Their speeches were particularly militant. When Stokely moved forward to speak, the crowd greeted him with a huge roar. He acknowledged his reception with a raised arm and clenched fist.

Realizing that he was in his element, with his people, Stokely let it all hang out. “This is the twenty-seventh time I have been arrested — and I ain’t going to jail no more!” The crowd exploded into cheers and clapping.

“The only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin us is to take over. We been saying freedom for six years and we ain’t got nothin. What we gonna start saying now is BLACK POWER!”

The crowd was right with him. They picked up his thoughts immediately.

“BLACK POWER!” they roared in unison.

Willie Ricks, who was as good at orchestrating the emotions of a crowd as anyone I have ever seen, sprang into action. Jumping to the platform with Stokely, he yelled to the crowd, “What do you want?”

“BLACK POWER!”

“What do you want?”

“BLACK POWER!!”

“What do you want?”

“BLACK POWER!! BLACK POWER!!! BLACK POWER!!!!”

Everything that happened afterward was a response to that moment. More than anything, it assured that the Meredith March Against Fear would go down in history as one of the major turning points in the black liberation struggle. The nation’s news media, who latched onto the slogan and embellished it with warnings of an imminent racial cataclysm, smugly waited for the predictable chaotic response.

From SNCC’s point of view, the march was a huge success. Despite the bitter controversy precipitated by Stokely’s introduction of black power, we enjoyed several important accomplishments: thousands of voters were registered along the route; Stokely emerged as a national leader; the Mississippi Movement acquired new inspiration; and major interest was generated in independent black political organizations.

One of our most important accomplishments was the deep friendship that developed between Dr. King and those SNCC members who participated in the march. I have nothing but fond memories of the long, hot hours we spent trudging along the highway, discussing strategy, tactics and our dreams.

I will never forget his magnificent speeches at the nightly rallies. Nor the humble smile that spread across his face when throngs of admirers rushed forward to touch him. Though he was forced by political circumstance to disavow black power for himself and for his organization, there has never been any question in my mind since our March Against Fear that Dr. King was a staunch ally and a true brother.

Tags

Cleveland Sellers

Cleveland Sellers was program secretary of SNCC and is the author of The River of No Return, from which this article is excerpted. Sellers is currently an administrator of the Greensboro, North Carolina, CETA program. (1981)