This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 3, "Passing Glances." Find more from that issue here.

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

The details are unique, but in broad outline, the story related below is hardly exceptional: a prisoner dies a slow death in his jail cell while his pleas for medical help are ignored. When reporter Jim Lee tried to expose the scandal, he met a bureaucracy working vigorously to conceal — and a press unwilling to reveal — the circumstances of Glenn Pitt’s death.

The events surrounding the death of Glenn Pitt illustrate both the inhumanity of what we euphemistically call our “corrections” system, and our desire to isolate it physically, morally and intellectually from our lives.

The problems of corrections and punishment will be the focus of the Fall, 1978 edition of Southern Exposure. Our reasons for devoting a special issue to prisons are many. Certainly we will witness in this era some crucial decisions concerning the criminal justice process in America. Whether those decisions involve radical shifts in philosophy, or mere cosmetic changes, the future of corrections in this country is to a large extent being charted today in the South.

A combination of factors makes the crisis in Southern prisons unique: a particularly acute overcrowding problem, the exhausted condition of our prison facilities, the region’s legacy of racial injustice, and a tradition of severely punishing criminals. Moreover, an aggressive federal and state judiciary has demanded sweeping reforms in the prison systems of Florida, Alabama, Tennessee and Louisiana. Georgia, Florida and Texas are made distinct by the fact that the Supreme Court has upheld their death penalty laws, and today more than 75 percent of the nation’s condemned prisoners await execution in Southern jails.

By compiling the best thinking on the subject from the system’s professionals, its victims and its challengers, we hope to stimulate interest and activity in efforts to bring a measure of humanity to our treatment of crime and criminals, and provide an educational resource for those struggling to rescue our criminal justice system from centuries-long isolation.

On the evening of December 24, 1977, Glenn Earl Pitt, an inmate at the Caledonia Prison Farm in Halifax County, North Carolina, was pronounced dead on arrival at the Scotland Neck Hospital. A routine autopsy by the North Carolina medical examiner’s office ruled that asthma was the probable cause of death.

The State Bureau of Investigation (SBI) conducted an inquiry into the circumstances surrounding Pitt’s death and forwarded their findings to District Attorney W. H. S. Burgwyn, who concluded after reading the report that there was no basis for bringing criminal charges against prison officials.

A letter from an inmate at the Caledonia facility to WVSP News prompted us to conduct our own investigation into the matter. Our conclusion is that Glenn Pitt did die of an asthma attack, but that his death might not have occurred had prison officials complied with the orders of medical personnel to transport him to a hospital. We have also found that prison officials as high up as the superintendent of the complex of Halifax County area prisons have engaged in a cover-up of the circumstances surrounding the death of Glenn Earl Pitt.

Glenn Pitt was 24 years old at the time of his death. He had been plagued by asthma since he was 14, and his condition was generally recognized as serious. He was strong, however, and with medication was able to control the ailment, although hospitalization was required from time to time. With his mother and sister he had moved from New York City to Enfield, North Carolina, mainly ,to get away from the New York air which aggravated his asthma.

In Enfield, a town of about 3,300 in the northeastern part of the state, Pitt fell in with a local man named Willie Mitchell who was involved in selling marijuana in the area. Pitt, along with a few other young men, worked for Mitchell pushing the weed. Mitchell had an unsavory reputation as an “Uncle Tom” and was frequently heard to brag about having control of the police department. Many people believed he was paying off the police in order to protect his drug sales. In fact, alleged attempts to bribe the Enfield police chief resulted in the arrests of Pitt and Mitchell in the spring of 1976.

Both men, through plea bargaining arrangements, were able to get suspended sentences. Pitt was given three to five years, suspended, on the condition that he pay a $1,000 fine through his probation officer, maintain a fulltime job and break no laws. Payments on the fine were set at $40 a month. According to Connie Pitt, Glenn’s sister, Mitchell promised to pay Pitt’s fine for him.

In the spring of 1977, Pitt was cited for being behind on his payments; his probation was revoked and he was ordered into the custody of the NC Department of Corrections. Judge Donald Smith’s order required a physical exam and treatment for Pitt, and recommended work release for the young first offender. Pitt was locked up on August 31, 1977. Willie Mitchell also ran afoul of the law and had his probation revoked. He, too, was sent to prison, and both men wound up at the Caledonia Prison Farm.

Pitt was considered a relatively well-adjusted inmate who got along with both prison employees and other inmates, though one prison staff member described him as “arrogant.” It was Pitt’s refusal to give in to authority when his rights were involved that brought him into conflict with a prison official, Captain Fredrick Rehnor.

On December 7, shortly before Glenn Pitt was to be shipped to Central Prison Hospital for treatment of his asthma, he was ordered to submit to a strip search. There are conflicting reports about what happened that day, but we do know that Captain Rehnor was involved. One reliable source told us that Pitt had complied with the search order except for removing his shoes and socks — which he refused to do because he was having difficulty catching his breath. Prison officials used force to complete the search. Captain Rehnor later filed a “Use of Force” report about the incident.

The die had been cast in the relationship between Rehnor and Pitt. Rehnor’s dislike for Pitt was rather widely known and Pitt was assigned to the segregation unit in punishment for the strip search incident. That same day, however, Pitt entered Central Prison Hospital, where he stayed two weeks. On his return to Caledonia, he was immediately placed in segregation.

On December 23, Pitt, still in segregation, was having difficulty breathing and saw Troy Dillander, medical supervisor of the complex. Dillander ordered Pitt transferred to the hospital for treatment. For some reason, Pitt was not transferred but instead remained in his small segregation cell. The next morning, Raymond Adams, a correctional health assistant assigned to the unit, saw Pitt and apparently found him in good shape. But later in the day Pitt developed more breathing problems.

Inmates in segregation are only allowed out of their cells for exercise in the custody of an exercise officer, and a duty officer is required to make checks of the area every 30 minutes, so it was virtually impossible for an inmate in distress to go unnoticed. Pitt’s condition was both noticed and reported by Quincy Wills, the officer in segregation that day, and by Sergeant Jesse Morgan, who was on escort duty.

We have not been able to determine when the first report of Pitt’s condition was made, but we do know that someone tried to call Adams, the health assistant, in the early afternoon. A prison employee who was on duty at the time told us that Adams called the prison at about 1:45 p.m. and told Wiley Davis, the officer who happened to answer the phone, to tell the officer in charge to get Pitt to the hospital. Officer Davis in turn told Sergeant Burger, the control sergeant that day, thus putting the information into the chain of command. Logically, Burger would have told either Ernest Smith, who was the shift officer in charge, or Rehnor, who was the weekend duty officer. We don’t know who Burger talked to, but we do know that more than one call went between the Caledonia unit and Adams’ Roanoke Rapids home.

Medical supervisor Dillander is also reported to have called the unit and ordered Pitt transferred. Our source says Dillander gave the order directly to Captain Rehnor sometime before 3 p.m., but still Pitt was not moved. A witness housed in the segregation unit says that Pitt was wheezing and begging for medical help, and that Sergeant Morgan made numerous calls for help over the intercom, but none arrived. According to one source, Captain Rehnor was aware of the situation from early afternoon and vowed to “teach . . . [Pitt] a lesson.”

As the afternoon progressed, Pitt’s condition worsened. Our sources say that between 6 and 7 p.m. he lapsed into a coma. He was finally taken to theScotland Neck Hospital where he was pronounced dead on arrival at about 8 p.m. The hospital is just 20 minutes from the prison. An inmate witness says the authorities carried Pitt from his cell on a stretcher, bound in leg irons and handcuffs, even though his body appeared lifeless at the time.

It is not clear why the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI) was called into the investigation. Ben Runkle, information officer for the prison system, said prison director Ralph Edwards ordered the probe. Prison administrator Fletcher Saunders says the investigation is a routine matter in all prison deaths. SBI agent W. H. Thompson, the investigating officer, referred all questions to District Attorney Burgwyn, who in turn says he isn’t sure how the investigation was initiated, even though the final SBI report was sent to him for evaluation.

The SBI refused to let a WVSP News reporter read the lengthy SBI report on the grounds that it is not a public document, but we have discovered that it contains statements from a number of prison staff members and at least one inmate, Willie Mitchell, the man arrested with Pitt on the charge of conspiracy to bribe.

We have not been able to confirm whether the report contains other inmate testimony, but we do know that on January 9, the reported time of completion of the probe, SB I agents had not talked to any of the inmates who were confined in the segregation unit and witnessed the entire sequence of events. Furthermore, the SB I investigators never contacted the dead man’s family and consequently did not have access to correspondence from inmates concerning the matter. Information held by WVSP News in the form of inmate correspondence has also not been seen by the SBI. We also know that the SBI report was sent to the typing pool as a complete report before the autopsy report was finished, although the medical examiner’s office did tell the investigator that asthma was the probable cause of death.

It is not clear why SBI agents avoided eyewitness testimony from inmates in segregation with Pitt but included testimony from at least one inmate who was not in segregation at the time of the incident. In short, there were serious shortcomings in the SBI investigation. Furthermore, there is reason to believe that information in the SBI report does not represent the whole truth.

Fletcher Saunders, the superintendent of the complex of prisons that includes Caledonia, hosted a late night meeting with prison officials on December 27 to discuss potential difficulties arising from the circumstances surrounding Pitt’s death. The testimony originally given by the two medical staff members was of special concern since they had both specifically ordered that Pitt be taken to the hospital. Both medics were urged to change their versions of what happened and both gave “modified” statements to the SBI. We do not know which statements were included in the report sent to Burgwyn, but we do know that the SBI has had access to both the original and modified statements from the medics.

Lieutenant Ernest Smith was the shift officer in charge on the day Pitt died, and as such had the authority to send Pitt to the hospital. According to our sources, Smith was specifically ordered by Captain Rehnor not to transport Pitt to the hospital until about 6 or 7 p.m. Smith’s original statement to the SBI said this, but that statement was later modified, too. Lieutenant Smith has since been promoted to captain. Dillander, the medical supervisor, has been transferred to another prison unit.

Willie Mitchell had a statement written on his behalf in which he claims to have seen Glenn Pitt flush his own medicine down the toilet. There is other inmate testimony, possibly from Mitchell, that Pitt would fake his asthma attacks as a means of getting sympathy. The thrust of the testimony tending to show Pitt as partially at fault in his own death is further enhanced by the portion of the SBI report describing Pitt’s removal from his cell. According to our sources, Pitt had passed out and was possibly comatose, if not already dead, when he was finally removed from his cell. The SBI report, however, contains a version of the final moments in which Pitt was placed on the stretcher because he refused to walk to the ambulance.

Inmates confined to the cells nearest Pitt at the time of his death have been transferred to other prison units and their status has been upgraded. Mitchell has been transferred to the nearby Halifax prison unit and promoted to honor grade. Sergeant Burger has also been transferred.

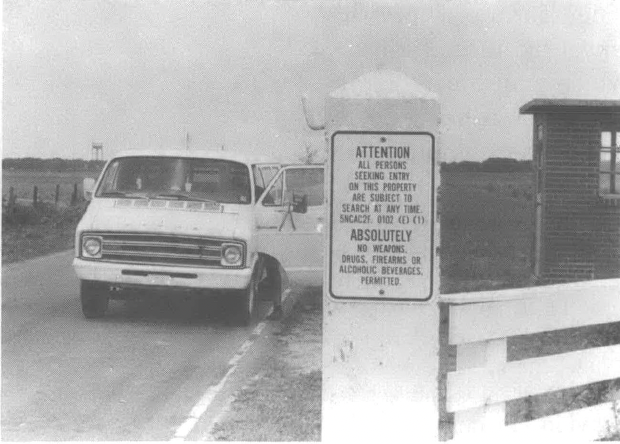

Caledonia Commander L. V. Stevenson granted WVSP News permission to interview inmates we believed would have knowledge of the facts in the case, but at the last minute, these interviews were cancelled without explanation. A credible source told us that five prison staff members connected with the case, including the two medics, went to Raleigh to take lie detector tests to resolve contradictions between their statements and Rehnor’s version. We have not been able to determine what the results of those tests were, if in fact they were carried out.

WVSP News reported the results of our investigation in our monthly program guide, Dialogue. Shortly afterward, the SBI reopened its investigation into Pitt’s death at the instruction of District Attorney Burgwyn. On April 21, two SBI agents visited Robert Harrell, an inmate who was confined to the segregation unit with Pitt at the time of the incident and who has since been transferred to a prison unit in Taylorsville, North Carolina. Harrell gave the SBI agents the names of two other inmates who were in segregation and witnessed the events of December 24.

Burgwyn has confirmed that he received the SBI’s latest report. He says that, based on the new information, he has something “stronger” than before, but still sees no basis for criminal charges.

Recently a claims adjustment officer for the Attorney General’s office offered to meet with an attorney retained by Pitt’s family, Charles Becton of Chapel Hill, to discuss a possible settlement of any claims against the state, even though Becton had not yet filed any claims. The adjustment officer, B. H. Whitehouse, told WVSP News that his action does not constitute any admission of wrongdoing on the part of state employees.

Even with the reopening of the investigation, most state officials have stonewalled attempts to get information on the case. SBI officers have refused to comment on the investigation, and prison officials have instructed all persons involved not to discuss the matter. When Fred Morrison, head of the Inmate Grievance Commission, a state agency, asked for information on Pitt’s death, he received a scathing letter from corrections adminstrator David Blackwell telling him not to make any further inquiries. A well-known jailhouse lawyer, Daniel Ross, has sued the SBI in an attempt to force the bureau to release its report.

Press coverage of this case, or the lack of it, has been of some interest. Both major wire services, Associated Press and United Press International, have had access to the story as we have reported it. So far these agencies have reported only the fact of Pitt’s death and the initiation and completion of the investigation. They have not covered the state’s offer to discuss a settlement and the reopening of the investigation. Needless to say, the WVSP report of the circumstances surrounding the death and the subsequent cover-up has also been ignored. Only the Carolina Times, a black weekly newspaper in Durham, has seen fit to cover the story in depth. One veteran wire service employee suggested that the tongue-lashing Governor James Hunt recently gave the press for its coverage of the J

oan Little case had made the wire services somewhat jumpy.

Tags

Jim Lee

Jim Lee is a professor of radio, television, and motion pictures at the University of North Carolina and a member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1992)

Jim Lee is news director at WVSP, a non-commercial, listener-sponsored radio station in Warrenton, North Carolina. (1978)