Case Study: Property for Prophet

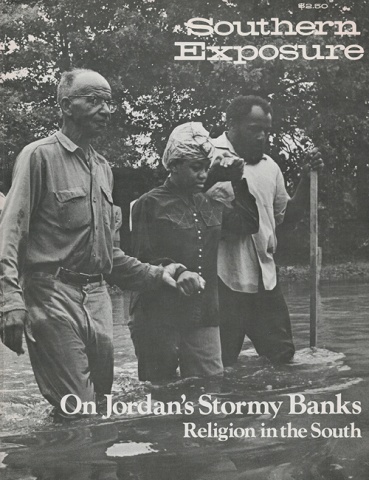

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Today it is known as Music City, USA. But long before the record discs launched it to its recent music fame, Nashville was well-known for another reason. To millions of Americans, Nashville, Tennessee, has always been, and still remains, the Religious Capital of the South, if not of the USA.

Within greater Nashville alone are some 313 local churches. More importantly, Nashville is the center of religious power from which emanate policies, publications, money and missionaries that influence the lives and thoughts of Christians throughout the South and around the world.

Along Nashville's James Robertson Parkway — an area that was once a black community, but now has been "urban-renewed" into one of Nashville's prime business districts — the headquarters of the Southern Baptist Convention presides over an annual budget in excess of $70 million and a lay membership of some 13 million. In less physical settings but nevertheless similar places of authority are the headquarters of the Methodist Board of Education, Discipleship and Communication, the Presbyterian Board of World Missions, and other smaller religion-related institutions.

Every year, Nashville produces millions upon millions of religious publications — hymnals, devotional pamphlets, study materials, bibles and magazines. The city boasts the largest religious printing plant in the nation (United Methodists), the largest religious publishing house (Southern Baptist Sunday Board), the largest Bible publisher (Thomas Nelson, Inc.) and the largest Bible distributor (Gideons International). Six denominations have publishing headquarters in the city, feeding literature to half the Protestant churches in the country. Together, these "Good Word" industries ring up close to $100 million a year in sales and provide for approximately one-fifth of the city's total manufacturing payroll.1

Nashville trains religious leaders, ministers and missionaries by the hundreds in institutions of religious education such as Belmont College (Baptist), David Lipscomb College (Church of Christ), Scarritt College (Methodist), Free Will Baptist Bible College, Madison College (Seventh Day Adventists), Trevecca Nazarene College (Church of the Nazarene) and Vanderbilt Divinity College. Together, the religious training schools occupy hundreds of acres of property and contribute substantially to Nashville's economy.

But it's not all give with religion in Nashville. Tourists come to the Religious Capital, not just for the country music, but for places like the Upper Room, the Methodist chapel and garden complex which last year attracted some 236,000 visitors from 50 states and 60 countries. Also to Nashville come dollars, lots and lots of dollars, collected from sales, tithes and offerings throughout the world.

In Nashville, religion, like music, is business, big business.

Nobody knows the business side of Nashville's religious institutions better than Jim Ed Clary, tax assessor of Davidson County. Church property in Davidson County, as throughout the country, is tax-exempt. In Clary's county, the exemptions take in the 313 churches, the religious headquarters, most of the publishing houses, and the religious education institutions. In fact, last time the figures were counted, 42% of the property in Nashville was taxexempt — a higher percentage than any other city in the country except Boston.

"Basically, it's a heck of a problem," says Jim Ed, looking from his courthouse desk out over an urban landscape clearly in need of funds and services. "Not a day goes by that we do not receive an appeal for exempt property. The burden must then be shifted over to other taxable property. . . . You either have to increase the value of the property or raise the tax rate. But when you put a higher percentage on people who can't afford to pay, it hurts."

Critics of religious exemptions often say that while it may be all right for a local church to get a tax break, the sprawling religious superstructure — land, apartments, hospitals, publishing houses, etc. — should not. In Nashville, the focus of controversy has been the massive religious publishing enterprises, especially the Baptist Sunday School Board and the Methodist Publishing House. The prime critic has been Clifford Allen, president of his Methodist Sunday school class and Davidson County Tax Assessor before becoming Congressman of the fifth district. In 1969, with the advice of the Metro Legal Department, Allen and the State Board of Equalization hit the Baptist Sunday School Board with $5,622,200 in new assessments and the Methodist Publishing House with $4,689,400. "I believe in the freedom of religion," Allen said, "but I don't believe in giving religion a free ride.

Like any good business, the publishing houses resisted the move. In announcing their intention to fight the matter through the courts, James Sullivan, then president of the Sunday School Board, said, "Further taxation of property devoted to religious purposes would be the start of an erosion process which would seriously impair the historic principles of separation of church and state and jeopardize religious freedom." Moreover, it was argued, the publishing houses are non-profit institutions, serving only to assist the denominations in spreading the faith.

Though legally non-profit, the religious publishing houses are assuredly money-making ventures, a fact which Allen and other non-denominational competitors in the publishing field have been quick to point out. Profits made by the Baptist Sunday School Board's sales are plowed right back into other non-paying Baptist programs. Profits from the Methodist Publishing House go to a pension fund for the "benefit of retired or disabled preachers, their wives, widows or children, or other beneficiaries." In 1975, out of $41 million in sales, the Methodist Publishing House had $1.5 million in net income, from which the ministers' fund gleaned $400,000.

After several years of legal proceedings, the Tennessee Chancery Court resolved the issue of whether the publishing houses should be exempt by ruling that the proportion of the buildings used for religious purposes should be exempt, while the proportion used for other purposes would be taxable. The publishing houses appealed the ruling to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which essentially upheld the lower court's decision. Both the Methodists and Baptists then appealed again, asking this time for clarification of exactly how the line between exempt and nonexempt portions would be drawn. In response the Supreme Court said that it was "mindful" that "certain types of governmental review could endanger concepts underlying the separation of church and state" and left the specifics essentially up to the "good faith allocations of the religious institutions." "Usually," says a lawyer in the Metro Legal Department," their 'good faith' places the assessments at about 20% for non-religious purposes."

For now Jim Ed Clary can live with the court's decision. However, he believes that the question of the responsibilities of local churches to the local government should now be raised. He suggests that maybe in lieu of taxes the churches should pay for the services they receive from the city. "It costs just as much to pick up the church's trash as it does yours or mine," he says, still looking out at Nashville's urban landscape.

"The Good Lord's not making any more land," he adds. "When it becomes exempt, we've got to make it up somehow."

II

If Nashville is the Religious Capital of the South, western North Carolina is its Religious Playground. There, surrounded by the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains, thousands of acres of land and buildings worth millions of dollars belong to religious assembly grounds, conference centers and campgrounds.

In the middle of it all, in Asheville, N.C., at least one man shares the perspective of Jim Ed Clary back in Nashville. "You've come to the right place," said Mr. Ed McElrath, Tax Supervisor of Buncombe County, when asked about the problem of tax-exempt property. McElrath has spent most of the last two years of his life attempting to list the parcels of property in his county belonging to owners who claim tax exemptions. So far, he's counted "between seven and eight thousand," and he's still got more to go.

Even without counting the numerous smaller property owners who claim a religious purpose, McElrath's county hosts many of the major assembly grounds in western North Carolina's panoply of religious recreation spots. They include:

acreage attendance/yr.

Montreat (Presbyterian) 3,600 2,900

Lake Junaluska (Methodist) 2,500 not available

Ridgecrest Baptist Conference 2,200 35,000

Young Life's Windy Gap 1,700 7,600

Kanuga Conference (Episcopal) 1,200 6,000

Wild's Christian Camp, Brevard 810 3,000

Christmount Assembly (Disciples) 640 6,000

Piedmont Presbyterian Camp 462 300

Our Lady of the Hills, Hendersonville 150 11,160

Camp Burgess Glen 150 9,900

A special section of the North Carolina state code provides exemptions for religious educational assemblies and any "adjacent land reasonably necessary," as long as they are used for religious worship and instruction. But, it's clearly not simply religious education that annually attracts the multitudes to these assemblies. In the South, at least, religious instruction isn't a commodity exclusive to western North Carolina; nor does it need a posh assembly ground in which to occur. As McElrath says, religious instruction is something "a lot of people do in their homes everyday."

Those who come to the religious assembly grounds come for other obvious reasons—to enjoy the hiking, riding, swimming, recreation and sight-seeing of the mountains— much of which is conveniently located on the assemblies' "reasonably necessary adjacent land."

Brochures advertising the religious assemblies differ little, in fact, from those of any resort. A handout of the Ridgecrest Baptist Assembly, for instance, describes in vivid color the "sights, sounds and surroundings" to be found nearby — including a golf course, the Biltmore estates and the Blue Ridge Parkway. "Nestled in the forested mountains, exquisite during the flowering spring, colorful in the red autumn and crisp in the sparkling winter, the center consists of thirty buildings in an architectural blend of Southern charm and modern usefulness," the brochure reads. Not a word about religious worship or religious education.

Historically, the church institutions grabbed their property in the wake of the Northern entrepreneurs who, around the turn of the century, centered upon the Asheville area as a land that neatly combined recreational pleasure with financial returns. George Vanderbilt was perhaps the best-known of these entrepreneurs who bought up mountain land. He visited the area in the 1880s and quickly acquired over fifty farms, which he developed into country estates and hunting lodges — gentlemanly supplements to his vast holdings of forest land.

Missionaries to the region, too, saw that the land's recreational potential could be of benefit. Montreat, the oldest of the assembly grounds, began in I897 as the Montreat Retreat Association. It was bought in 1905 by the Presbyterian Church for a summer conference ground. Ridgecrest's initial 850 acres were bought by the Baptists in 1907. Lake Junaluska, now the 2,500-acre World Methodist Center, was first purchased by a Methodist missionary movement in 1908.

In more recent years, the lush mountains of western North Carolina have again become the scene of a booming land-recreation-resort complex. Natives of the region have begun to wonder who benefits from the presence of industry — the area and its people or the owners and the affluent, urban tourists who can afford to pass through. The citizens' concerns touch also on a related question: are the vast religious holdings any different from the private corporations which exploit the area?

The manager of Ridgecrest, which annually has 35,000 visitors and a budget of $3 million answered in a way that gave cryptic comment to the power of the religious assemblies in the area: "I'm unaware of the question," he said. "I have not known of any negative impact. Our whole community is built on what comes in to the conference center. If we were to pull out, the community of Black Mountain wouldn't have anything left. They (the people of Black Mountain) certainly wouldn't even raise the question."

Tax Supervisor McElrath doesn't quite agree. He doesn't object to the presence of the religious assembly grounds which, he admits, help local business. But he does question their preferential tax treatment which excludes them from the responsibility of supporting local government.

"The whole system is subject to abuses," McElrath says in his quiet manner. "It's not that I'm against religion or charities, but I've got so many things that nobody knows what they are."

As an example, McElrath mentions the World Evangelical and Christian Education Fund, a group which recently bought just under 2,000 acres of land in Buncombe County for an estimated two million dollars. While he expects to receive a tax-exemption request from them, McElrath doesn't have an inkling of who the World Evangelical and Christian Education is or what it will do with the property. He suspects that maybe it's a front for "either Graham or Moon."

For McElrath, its not just a question of who owns the land but also how it is used. He questions whether the thousands of acres of land owned adjacent to the assembly ground are necessary to their religious purpose. He wonders whether certain individuals aren't gaining unduly from the religious assembly law. He points to Deerfield, an organization chartered "to provide a comfortable and congenial home for aging members of the Protestant Episcopal Church" but which, in McElrath's view, is just a haven to provide homes for "good Episcopalians." He claims, and court records substantiate, that certain assemblies which have held land for years are now selling off lots to selected laymen or ministers for summer cottages. He describes the religious assemblies as if they were no different from real estate dealers or land speculators. "These organizations are going to defeat their purpose by abusing these laws," McElrath has decided.

"The Constitution talks about church and state, "he continues. "But this defeats it All of these organizations are being supplied water, sewers, fire protection and the like. They're automatically tied to the state. It forces everybody to support these organizations, and the list goes on — The Elks, Moose, Eagle The guy out here who doesn't belong to anything is supporting them all through these exemptions."

So far, there haven't been any complicated, drawn-out law suits about religious exemptions in Buncombe County, as there have been in Nashville. To Ed McElrath, there's an easier way to deal with the problem: "I think all exemptions should be eliminated," he ventures. "That would eliminate the abuse. It would help everybody. Then the Baptists would pay for what the Baptists get and enjoy."

1. Some of this data is drawn from Richard T. White, “Bibles are Big Business,” in The South Magazine, July/August 1976, pp. 51-53.

2. Quoted from Beverly A. Asbury, “The Southern Baptists: Between a Rock and a Hard Place,” unpublished paper, 1970. Thanks to Bev Asbury for permission to use his research.

Tags

John Gaventa

In researching "Food Festivals," the authors logged over 75,000 miles by car, bus, plane, and boat. In addition, they have the world's largest collection of food festival T-shirts. (1986)

John Gaventa is on the staff of the Highlander Center. Bill Horton is on the staff of the Appalachian Alliance. Both are in New Market, Tennessee. (1982)