This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

From the Ozark hills to the Texas border, from the sparsely settled Delta to scenic Hot Springs, energetic Arkansans are gathering signatures for a people's referendum. They plan to put a constitutional amendment on Arkansas' November ballot allowing workers in union plants -- some 100, 000 strong - to vote on whether they want a union security agreement.

The Council of Churches' chief deacon has joined with the young president of the Junior Chamber of Commerce. Leaders from the CIO, the UAW, Teamsters, and Mineworkers have sealed a pact with the NAACP and the former dean of the University Law School. Small businessmen - barbers, druggists, and others -- have rekindled the old Populist alliance with the head of the state Farmers Union. They have all joined together and formed Arkansans for Progress.

In simple terms, Arkansans for Progress is attempting to accomplish what no other state has done since 1957: to repeal a state's "right-to-work" law. But the phrase is misleading. In Arkansas, we refer to the law as the "right-to-work-for-less." Eugene Debs introduced the catchy words as a plank in his Socialist Party presidential platform; "Every man has the inalienable right to work." And Franklin Roosevelt blessed the phrase as well as the concept in his Economic Bill of Rights, calling for "the right to an useful and remunerative job. But anti-union forces overcame the late FDR with their Taft-Hartley Act in 1947, which included the fateful Section 14B, outlawing the closed shop and enabling states to ban union security clauses. Through a stroke of public relations brilliance, management turn ed the leverage of 14B into a word twisting ploy and dubbed the new state laws which sprung up, "right-to-work" laws.

In 1944, three years before Hartley even passed, the voters of Arkansas approved Amendment 34 to the constitutuion. It was called the Rights of Labor, and it prohibited union security agreements. The state's constitution, in the absence of Section 14B, was actually in violation of federal law. Then, in 1947, after Taft Hartley, the state legislature passed the enabling law, making Arkansas the first state with a so-called "right-to- work" statute.

And right-to-work-for-less has been with us ever since. In 31 states, local unions and managements have the right to agree to union security pro visions in their contracts -- a "union shop" or an "agency shop." In the remaining 19 states (including all the Southern states except Louisiana, West Virginia, and Kentucky), a state government provision mandates the open shop, which prohibits either type of union security agreement.

Right-to-work-for-less has taken its toll. In 1948, Arkansas was $555 below the national average in per capita income. By 1974, the state was $1,248 below the national average of $5,448.

Arkansas permits its voters to petition for constitutional reform and changes in the law. This method has been used before. In 1964, groups led by the League of Women Voters removed the poll tax and passed a personal registration law by this route.

Like those reformers of 1964, Arkansans for Progress has a lot in its favor. Some 100 employers in the state - including major firms like Safe way, Southwestern Bell, and Reynolds Metals - already have "if and when" clauses negotiated in union contracts. This means that these companies have signed union security clauses into effect IF the majority of eligible employees vote for such a clause and WHEN such agreements are legal in the state.

If the coalition effort proves successful, the amended state consti tution would allow union security agreements: (1) where a majority of the employees in the existing bargain ing unit vote for a union security pro vision in a secret ballot election con ducted by the Arkansas Department of Labor; and (2) where management agrees -- that is - whether the contract shall provide for a union shop or an agency shop would be a matter for collective bargaining.

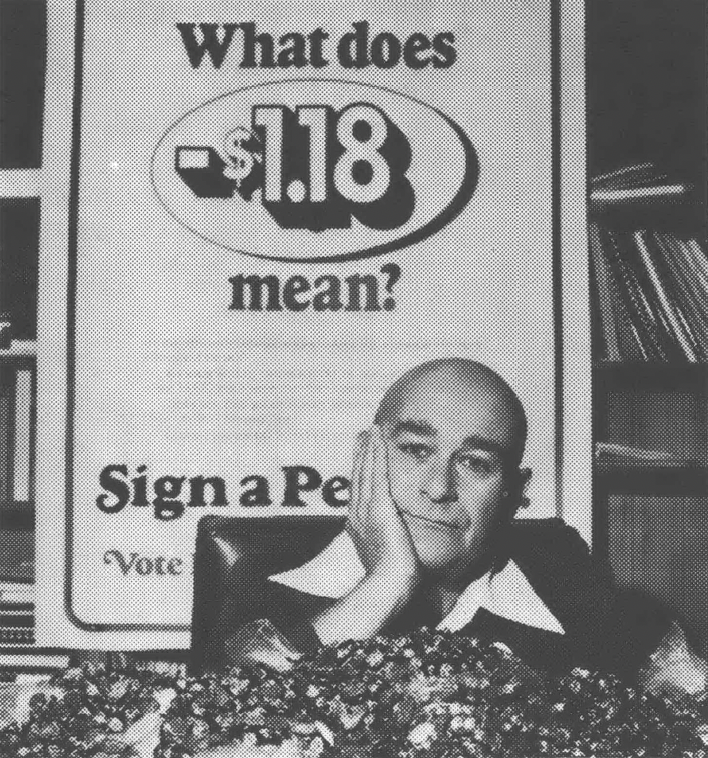

The group has mounted a spirited campaign to get the required 55,000 signatures by the July 2 deadline (10 percent of the votes cast in the last gubernatorial election). But the campaign coordinators hope for a symbolic 106,000 signatures -- 1000 more names than the total vote cast in 1944 for the so-called "right-to-work" amendment. Early ads centered around the simple figure, "$1.18,” the amount Arkansas' hourly wages were below the national average. But the Department of Labor released updated figures to show that Arkansas had dropped to $1.23 below the national average! United Labor of Arkansas (the four labor bodies involved in the coalition) used the release as a plug for the campaign. "What do you do with 35,000 buttons that say — $1.18?” the group asked at a press conference. Meanwhile, the word about the proposed amendment was spreading.

It traveled all the way to Arlington, Va., where Reed Larson heads the National Right to Work Committee and the sister National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation. Noted for anti-union campaigns of all sorts, the group has been pressed by the courts in recent months to disclose a sampling of their contributors. A coalition of liberal unions had sued, alleging violations of labor laws and claiming specifically that the Foundation mainly funnels employers' money into suits by their employees against their unions. The early rulings have favored the unions. Meanwhile, Larson has not neglected other causes.

Ever since he led right-to-work activists in banning the union-shop in his native Kansas, Larson has fought the union movement. And now he has directed his attention back into Ameri ca's heartland, sending money and muscle into Arkansas. Larson recently sent a "Warning Actiongram” to Arkansas Right to Work members claiming, "If Arkansas voters are hood winked into approving this outrageous proposal, it will rob workers of their right to earn their livelihood without paying tribute to labor bosses and will also retard your state's economic prosperity.”

Larson contended to the Wall Street Journal just last year that "we're not against unions at all," but merely against "compulsory” membership. Larson is surely intelligent enough to understand that the amendment to the Arkansas constitution would allow un ion and management to freely negotiate a union security agreement, after the employees have voted on such a provision. But according to his own memo, Larson feels that the prestige of the Arkansas Jaycees, the Council of Churches, and the Roman Catholic Bishop (all supporters of the amendment) "is being exploited to inflict coercive unionism on Arkansas wage-earners.”

The United Labor of Arkansas leadership has succeeded in mounting an unprecedented campaign to rid the state of right-to-work-for-less. Congressman Wilbur Mills has endorsed the effort, and Gov. David Pryor has remained neutral. The liberal coalition realizes that union security agreements would add to the economic buying power of the state and upgrade the at tractive features for new industry.

Arkansans for Progress represents a coalition effort that can be instructive to other states. In neighboring Louisiana, for example, a strong right-to- work effort may succeed in repealing their current union security law. Not only can coalition efforts, spear headed by state labor bodies, be successful in blocking regressive movements like that in Louisiana, but coalition groups can also muster the collective power to regain the positive outlook towards negotiated union security agreements once preserved during the Wagner Act of Roosevelt's day.

Tags

Bill Becker

Bill Becker is President of the Arkansas AFL-CIO. He came to Arkansas with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union. He joined the Arkansas AFL-CIO in 1960 as secretary-treasurer and has served as president since 1964. (1976)