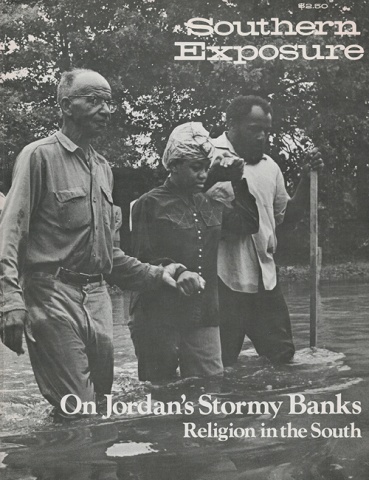

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

The Jewish kids played in the pasture, a sister and brother in an Alabama town. Soon the sun would set and Chanukah begin. The dry field grass scratched her legs when, Indian wrestling, she rolled on the ground to break a fall. The incredible blue sky, sunless, chilled the sweat that sank salt into new wounds.

The wrestling became a spat and he left victorious. The girl played on alone, a new game. She pretended the holiday was not her own. She was neuter, no, a Christian, a Gulliver pinned by Jew hammers, Jew strings, and Jew nails, changed for a night to a Jew.

Her parents explained that it wasn’t so bad. She had eight days of Christmas, not a sickly one. Eight times the joy! Eight times the gifts! Except she was ten, and she would only have one gift this year. And eight times the void on the other nights.

“Why is this night different from all others?” She didn’t know what to say to the boy who came through the field with a cow. Bovine both, she was terrified. What if he asked another unanswerable question? Like “How come you’re not saved?” She lacked the gifts to make herself understood and ran away mutely, leaving him laughing at the shit on her shoes.

Better stay near the house now. The sky was red.

Her little sisters played store in the back yard. They still had eight days — she’d seen the tiny oven that was the first of this year’s potlatch. On the back stoop she watched them imitate a mother and friend: they did not ask her to join in. Impatient she found a stick and cleaned her shoes.

Sundown was close. Where should she be when they called?

She ran to the front yard, to the pecan tree with the rounded crotch that was her favorite perch when she was little. Tonight she was grown up, though. A more dignified spot was required. In the orchard down by the wild plums perhaps — but she’d eaten the fruit already and she’d only get dirty on the red clay bank.

She was running to the grape arbor when she heard the call.

Eldest, she lit first, a pink shamas and a green spiralled taper, and read prayers from the paper that came with the candles. The two lights flickered in the silver menorah. She wanted to touch the flame, but was afraid. “Boruch atoy adonay.” She wondered at the ancient violence and longed for the prince of peace, for the easy tunes of Christmas instead of the tortured cadence she now sang. “Rock of ages let our song, vast thy saving power. Thou amidst the raging foe wast our sheltering tower.”

They brought out the gifts, unwrapped as always. The first of eight for the others, one alone for her. A doll. Her friends had dolls and she’d wanted one too — but not like this, a lady doll with embarassing breasts, red lips and bouffant hair. She hated it, but acted pleased so no one would say she was childish.

Seven nights she brought the doll woman out, the badge of her growing up. Seven days she hid it in her room. On the eighth morning her brother found it and drew nipples on its breasts and a moustache of pubic hair between its legs.

That afternoon she went out to see what her friends had under their Christmas trees: skates, baby dolls, chemistry sets, BB guns, footballs and bikes. They were all laughing as they played, joking about how hard it was to be good all year.

The girl ran home crying. She cried because of the doll. She cried because she was captive, imprisoned where she did not belong. She cried because her parents had lied when they said there was no Santa Claus.

Tags

Janet Rechtman

Janet Rechtman is a poet and writer from Atlanta, Georgia. She occasionally writes for the Atlanta Gazette. (1976)