The Cherokee Connection

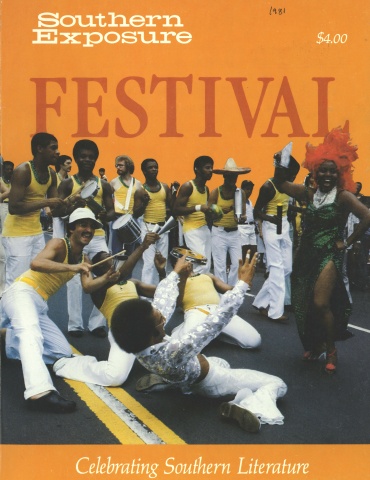

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

“If it is not of the spirit, it is not Indian.” The grandfathers have said so. “Speak of the spirit in symbols or in silence. Only listening ears will hear.” The grandmothers have said so. I ask you to remember.

It is difficult to go against the advice of the grandmothers and speak about my Cherokee heritage in straightforward prose because I understand the warning implicit in their words, as well as the reason behind it: deaf ears destroy.

Raymond, a wiry and seasoned journalist, warned me in a different way. “Most Americans have concrete minds. They don’t know a symbol from a hole in the wall. If you can’t explain things to them in terms of the Gross National Product, forget it. Right?”

“Mostly right. But Raymond, some Americans believe. . . .”

“Some. How many? Enough to make any difference? Look at the Tellico Dam controversy here in Tennessee. The Cherokee fought that dam for 15 years on the grounds of spiritual and human rights. And what happened?”

“They got crushed by concrete.”

“You know why. With no power and no money, they went against the big interests. You wrote three articles about it. You gave the facts, but your basic appeal was to the spirit, to the conscience. You should have stuck to the dollar.... In this society, the dollar’s the bottom line.”

“I was asked to write from the Cherokee point of view, and the grandfathers have said....”

“I know what they said. But the Indian point of view is obsolete. Indians are being phased out. You said it yourself in the Tellico article. ‘The waters are rising for us all.’ The spirit is out, technology is in. Solid concrete. That’s the way it is.”

Raymond goes to the newspaper office every day. Some of his best stories come back with the editor’s “public not interested” scrawled across the top, but he keeps working for what is humane and just. Raymond has “listening ears.” He is a crack in the concrete.

There are many people like Raymond, but they are in the minority. The overwhelming mindset in America is: get the GNP up and all will be well. Reduce everything to its category and eliminate what is irrelevant. Keep it rational. Keep it objective. Keep it concrete.

But the grandfathers have said, “If it is not of the spirit, it is not Indian.” Is this way of thought obsolete? Are the first natives of America being phased out because they are irrelevant?

There are signs to the contrary. Native American art is beginning to boom. Hanta Yo is a best-seller. A play about Black Elk is opening in New York. More people are visiting reservations, buying crafts. These things indicate an objective interest. But do they mean more support for Native American issues and an increasing acceptance of the Indian way of thought? Are there more people with listening ears?

How to answer these questions? As a poet of Native American descent working in the South, I’m wary of ignoring the grandmothers’ advice and stepping from poetry into prose. From my experience at Tellico and elsewhere, however, I know that deaf ears destroy. Perhaps straightforward words will help cultivate more true listeners.

“If it is not of the spirit, it is not Indian.” The grandfathers have said so. Because it is of the spirit, the Indian way of thought can pass through generations, through ethnic mixes, through different languages and still retain its essence. As they say in my native Appalachia, “Indian blood is strong.” I have listened to my blood, to my mother and her father, who are of Cherokee descent, and to the silent voice of the mountains. This is what they taught me:

All are related in spirit; each has a part in the whole — be reverent. Keep your body, mind and soul as one. Understand nature and live in harmony with it. Remember that life moves in a circle: past, present and future are one; death is part of life; the spirit never dies. God is a spirit.

This way of thought is my still-center, my inner force. It shapes my life and work. If I had grown up in a traditional Southern town, I might not have been able to withstand the pressure from a different cultural set. Fortunately, in 1945, my family moved from Knoxville to Oak Ridge, Tennessee. I was nine years old, just the right age to absorb the rhythms of the atomic frontier.

There were no traditions, no paved streets, no class structures, no sidewalks, no private clubs, no “old families” controlling things, no one to say, “It’s always been done this way.” From across America 75,000 people had come to build a new community. They brought different customs, ideas, religious beliefs. Most important, they brought youth and flexibility. I was free to create a life pattern to suit myself.

A given of that pattern was the reality of the intangible. Life in Oak Ridge revolved around an invisible power — the atom. My friends and I accepted it as a matter of course. My cousin, who was visiting from West Virginia, could not. (Her father was in the coal business.)

“What does your daddy do?” she asked me.

“Something with the atom. He’s not allowed to talk about it.”

“Have you ever seen an atom?”

“No.”

“Have you ever touched one?”

“No.”

“Then you can’t be sure it’s real.”

“That’s crazy. Atoms are everywhere, in everything.”

“I don’t believe in atoms,” she said.

But the atom is real. The spirit is real. They are intangible, unifying forces. I knew it in my childhood, roaming the woods around the house. And I know it now as I try to form my life and work into a harmonic balance.

Every day I am reminded that this wholistic approach is not the American way, which is in the Western tradition based on the ancient Greek dichotomy of body and soul. That dichotomy is now subdivided into so many categories, specialties and labels that life sometimes seems insupportable. American culture is a tapestry cut into fragments. Some writers describe the fragments. Others, like myself, try to find a way of weaving them together again.

My way is through the Cherokee connection, which is fused with elements of Appalachia and the atom. It is a spiritual connection. In the South there is the tradition of concern with the spirit: among both blacks and whites it rests solidly in orthodox religion; among some blacks it is more wholistic, reaching back to African roots. Nevertheless, it is wiser in the South, as elsewhere, to speak of the spirit as the grandmothers advised, in symbols and in silence. My first book of poetry, Abiding Appalachia: Where Mountain and Atom Meet, was published in 1978. In content it is obviously in harmony with my origins. In form the harmony is less apparent because it is less familiar.

I followed the Cherokee oral tradition, which is basically Eastern. Like that of the ancient Hebrew poets, it creates rhythm not with rhyme and meter as in standard Western poetry, but with the movement of the thought itself, by repetition and alternation. Imagery and cumulative symbol are also important. Along with these elements, I used Western interior rhyme.

Silence is an integral component of Abiding, and of all my work. It is the Indian way to speak cryptically, then to be silent, leaving time for the “listening ear” to expand and connect. This method is very much akin to the Oriental principle of negative space, which is why the layout designer used that principle in my book. It is also why some readers love Abiding and others dismiss it as trivial. Deaf ears turn away, as I intended that they should.

Like my Cherokee ancestors, I am reverent toward nature, not romantic. When I say I “listened to the silent voice of the mountains,” I am not ascribing human qualities to them, as romantics do. Rather, I mean that the mountains speak to me of themselves, of their essence. With that concept in mind, I designed a logo for Abiding, which is also the symbol of my life and thought: the sacred white deer of the Cherokee, leaping in the heart of the atom.

I found the myth of Little Deer in James Mooney’s 1887 book Myths and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee, which he translated from the sacred books of Swimmer, a revered shaman of the Eastern Band. According to the legend, every hunter knew that if he killed a deer and failed to perform the ritual of pardon, Little Deer would come, swift and invisible, to cripple him for life. Only the greatest masters of the hunting mysteries ever saw Little Deer, and then perhaps only once in a lifetime. Although he could be wounded and a piece of his horn taken as a charm for the hunt, the white deer was believed to be immortal.

When listening ears hear the story of Little Deer, they recognize him immediately as a symbol of reverence and hope. That is why I put him in the center of the atom. Without reverence for life and for the basic physical and spiritual power of the universe, the human race will be phased out. We will do it to ourselves. The most rational minds, the best technology, the most solid GNP cannot prevent the explosion. What can prevent it is the human spirit pushing with the gentle insistence of a burgeoning seed to crack away all that would keep it from the light.

Hope for this seed keeps me writing. I want to explore and nurture its power, for it can break through concrete barriers that separate us from ourselves, from each other, from nature and from the spirit that binds us all. I work through my Cherokee connection because it is the only way I know.

“If it is not of the spirit, it is not Indian.” The grandfathers have said so. I speak of my heritage believing that yours is as important as my own. We are one. I ask you to remember.

Coal Field Farewell

“Mama, I’m goin’ now ... to church.”

His quiet words trailed smoke-like

and curled around her at the stove.

She watched the heating skillet —

black as the mine’s mouth, black as

her man’s face when they’d brought him up,

black as a rotten lung.

The silent ritual had begun and her

son stood by the door — skin so white,

hair with raven’s sheen; tall he was and lean.

She’d told him before, “A man earns his own way.”

And now the day was here — he was fifteen.

She remembered him at four saying,

“If I was bacon in a pan, what would you do?”

“Why son, I’d tend you careful-like

and lift you out. I’d lift you out for sure.”

“. . . to church,” he’d said and knew she’d seen

the suitcase cached among green laurel.

“Mama . . . ?” Their eyes met.

“Go along now,” she said. And then

his step was on the path. Too tired for tears —

with ten children more to rear — she laid a

strip of bacon in the pan, watching it careful-like

and listening to the deepest hollow of her heart.

Women Die Like Trees

Women die like trees, limb by limb

as strain of bearing shade and fruit

drains sap from branch and stem

and weight of ice with wrench of wind

split the heart, loosen grip of roots

until the tree falls with a sigh —

unheard except by those nearby —

to lie . . . mossing . . . mouldering . . .

to a certain softness under foot,

the matrix of new life and leaves.

No flag is furled, no cadence beats,

no bugle sounds for deaths like these,

as limb by limb, women die like trees.

An Indian Walks Within Me

An Indian walks in me.

She steps so firmly in my mind

that when I stand against the pine

I know we share the inner light

of the star that shines on me,

She taught me this, my Cherokee,

when I was a spindly child.

And rustling in dry forest leaves

I heard her say, “These speak.”

She said the same of sighing wind,

of hawk descending on the hare

and Mother’s care to draw

the cover snug around me,

of copperhead coiled on the stone

and blackberries warming in the sun —

“These speak.” I listened . . .

Long before I learned the

universal turn of atoms, I heard

the spirit’s song that binds us

all as one. And no more

could I follow any rule

that split my soul.

My Cherokee left me no sign

except in hair and cheek

and this firm step of mind

that seeks the whole

in strength and peace.

Star Vision

As I sat against the pine one night

beneath a star-filled sky,

my Cherokee stepped in my mind

and suddenly in every tree,

in every hill and stone,

in my hand lying prone upon

the grass, I could see

each atom’s tiny star —

minute millions so far-flung

so bright they swept me up

with earth and sky

in one vast expanse of light.

The moment passed. The pine

was dark, the hill, the stone,

and my hand was bone and flesh

once more, lying on the grass.

Tags

Marilou Bonham-Thompson

Marilou Bonham-Thompson is a Memphis writer whose Abiding Appalachia: Where Mountain and Atom Meet (St. Luke’s Press) is the first book of poetry and prose to come out of the experience of growing up on the atomic frontier in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. She has also written widely about the Cherokees’ battle against the Tellico Dam. “Coal Field Fare well” first appeared in Gayoso Street Review; the other poems are from Abiding Appalachia. (1981)