This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 3/4, "No More Moanin'." Find more from that issue here.

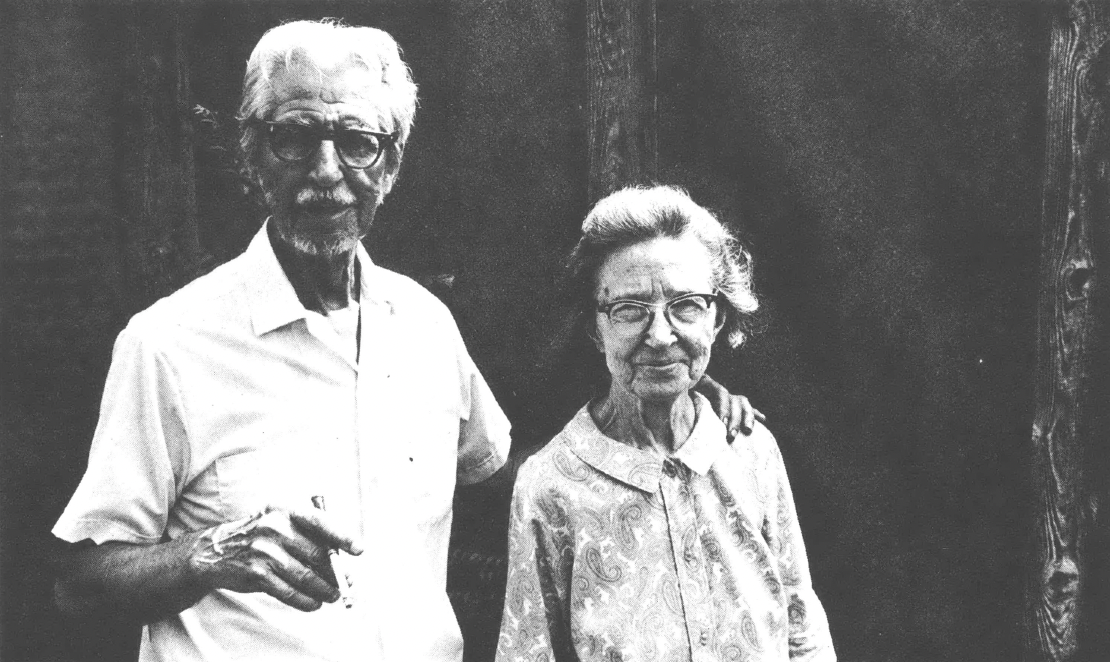

Few American radicals have displayed as much consistency in the face of the ups and downs of American politics as Claude and Joyce Williams. From their initial political involvement with the miners and sharecroppers of Eastern Arkansas in the early Depression, they have played an active role in the southern organizing drive of the CIO, the interracial work of the UAW and other unions in wartime Detroit, the voter registration drives and desegregation campaigns of the late fifties and early sixties, and the rise of the student movement and the peace movement in the South. Throughout their careers, they have experienced both physical persecution from the right, and suspicion and skepticism from many people in the organized Left.

The history of their work merits particularly close examination at this time, when the Left in America appears to have lost some of the momentum and effectiveness it displayed in the 1960’s. The re-election of Nixon marks the naked hegemony of the corporations in all areas of American life. The mood of optimism and expansiveness of the Sixties has given way to pessimism and despair. Whereas we were once able to sustain ourselves on the unfolding energy of blacks, students and women asserting themselves after years of political passivity, we now confront the limits of the “New Left Coalition;” none of these movements, individually or collectively, proved capable of resisting the militarization of American society or achieving more than localized reforms. The building of a revolutionary movement, or even the protection of traditional American rights and liberties, requires far broader participation from the mass of American working people than we had initially envisaged, and many in our ranks were unable to adjust to the demands of the new situation.

Fortunately, the present deterioration of the American economy has begun to lay the basis for the re-emergence of working class radicalism. Nixon’s economic policies represent a freezing of both living standards and class boundaries. Since much of the “passivity” of the American working class in the postwar period can be attributed to an unprecedented rise in real wages and a vast expansion of educational opportunity, it is reasonable to expect a resurgence of class politics, if not class consciousness and class struggle. Certainly the corporate elite and the upper middle classes have become more “class-conscious”—the working classes could very easily move in a similar direction in the next few years.

However, the thirty year absence of a class oriented Left has taken its toll. Most of the “natural leaders” of the American working class have been either assimilated upward through the mass educational institutions or have become entrenched in trade union bureaucracies. Perhaps the only arena for working class self-activity has been local politics—where the right has been far more active than the left. Nevertheless, it is from such leadership that any class movement will emerge, not from the remnants of the new left. So those of us still “alive and kicking” have quite a political chore; to work with and align ourselves with emerging working class protests and leaders who have no traditional orientation toward Marxism, Socialism or revolutionary objectives.

The Communist and Socialist parties in America have historically been unsuccessful at inspiring popular working class movements based on American cultural and political traditions. However, some people within these organizations have been able to “translate” revolutionary concepts into popular idioms with striking effectiveness. The socialist journalists Oscar Ameringer, editor of The American Guardian and Bob Ingersol, editor of Appeal to Reason, Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs, union leader Harry Bridges, and radical congressman Vito Marcantonio, are examples of people who built massive constituencies within the framework of socialist or communist programs. They are among the few truly “charismatic” working class leaders that have emerged on the American Left.

Claude and Joyce Williams fall within this tradition. They are among the few twentieth century radicals who have been able to communicate effectively with the people of the American South. In a section which has never lacked for grass-roots leaders and mass movements—mostly conservative—they developed an approach to black and white Southerners that uses the Bible as a reference point for class struggle, civil liberties, and racial brotherhood. While never intending to become the leaders of an autonomous “movement” or “crusade,” the Williams have used this approach effectively in both the trade union movement and the civil rights struggle. A brief analysis of their careers is useful, both for the exposure of their philosophy, and for the popularization of methods of political work that have continuing applicability.

“God said It, Jesus Did It, I Believe It, and That Settles It!”

Claude and Joyce met in the 1920’s when they were students at Bethel College in Tennessee, the seminary school of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Both came from families which had no historic connection to radical movements; Joyce’s parents farmed in rural Missouri, Claude’s in the hills of Tennessee. In the communities where they grew up, the church was the sole outlet for humanitarian impulses and aspirations to social leadership. To “do good” for people was to save their souls. As Claude put it: I at first conceived my purpose to preach the redemption of men’s souls from hell to heaven. When I joined the church and entered the ministry, my purpose was to preach the gospel of repentence and salvation by faith in Jesus Christ.

The Williams began their ministry in the small town of Auburntown, Tennessee, and settled down to raise a family. Claude rapidly achieved a reputation as a preacher who could make people “experience” their religion. His parishioners left church burning with the desire to live righteously and trembling with fear of the hell Claude so graphically described [I preached till they could feel the flames lapping around their legs]. Away from the pulpit, Claude and Joyce seemed the ideal ministerial family—attractive, pious, sociable— and they reaped the rewards of their position. They were well-housed, well-fed and bathed in social approval.

Yet there were stirrings of dissatisfaction within them. Even within the “literalist” terms of their religious beliefs, disquieting questions arose. Were the members of the church taking their religion seriously? Was the comfort they endowed the minister with a reflection of their piety, or a subtle incentive to politely acquiesce in their sins? The “righteousness” Claude strove to move people towards seemed absent from their daily lives, and his very seriousness and enthusiasm was offended by their hypocrisy.

Moreover, Claude found the treatment of the black people in the community disturbing. Although white supremacy had been part of Claude’s background, both he and Joyce had come from “hill” areas where the black population was small, and they were not prepared for the systematic humiliation of black people that they observed in Auburntown. They made gestures of Christian concern toward the local black community, preaching at the black church and helping to raise money to rebuild it. Although such actions were not antagonistic to the southern tradition of paternalistic race relations their contact with the black community provided the Williams with an image which simply did not fit the racial perspectives Claude had been taught. (Joyce's familv had been free of such stereotypes.) They kept their doubts to themselves for the time being, but these feelings contributed to a growing sense of discomfort with the “southern way of life.”

The very effectiveness of the Williams’ ministerial labors, their charisma, and the respect with which they were held by local people, contributed to the sense of constriction they experienced. The more emotional the congregation’s response, the greater the church attendance, and the more impressive their reputation, the more they hungered for reading materials, outside contacts, and more sophisticated and informed discussion of theological and social issues. It was as though the Williams’ success in conventional Christian labors only served to dramatize the insufficiency of those labors by biblical standards of righteousness. They read avidly in the few magazines, newspapers and books that were available to them in their local community, and looked forward to a chance to expand their frame of reference more systematically.

That opportunity became available in 1927 when Dr. Alva Taylor began offering a series of courses on contemporary religion at Vanderbilt Divinity School in nearby Nashville that were designed specifically to broaden the perspectives of southern churchmen. Claude asked for a leave of absence to enroll in this program and found himself placed in a milieu which provided unimagined opportunities for intellectual and theological growth. Not only did he find religion emancipated from narrow debates over immersion, baptism and the nature of the trinity, but he found himself in a community of people committed to connecting theological issues to all aspects of life. A number of young southern preachers there found the analytical and comparative approach to religion as “liberating” as Claude did, and were equally committed to making the church a vehicle for social reformation. Such views, commonplace in many Northern seminaries, had an extraordinary freshness to young southerners brought up in biblical literalism, especially when presented by a man like Dr. Taylor who came from a similar background. Claude and his fellows—Don West, Howard Kester, and Ward Rodgers, all of whom were to play an extensive role in socialist and trade union activity in the south—developed a collective conception of their social purpose: to make religion assume its proper role in modern society.

When the sessions were completed, the Williams’ sense of restlessness was even greater than before. The experience at Vanderbilt, Claude recalls, had stripped the aura of “sanctity” from Jesus Christ, and allowed him to stand as the Son of Man, a human figure whose actions and purposes were explainable in human terms. It was less and less possible for Claude to preach the joys of heaven and the terrors of hell without feeling hypocritical. He had begun to conceive of God’s purpose to be the establishment of a Kingdom of God on Earth, a Divine Republic, or a completely democratic republic. With such an outlook the social inequities that surrounded the Williams became increasingly difficult to separate from their ministerial duties and aims. The “great fixed gulf” they saw between the planter and the sharecropper, between the property owners and those who worked with their hands, between the black and white people appeared as concrete obstacles to the achievement of God’s will. They had to preach on these themes to be true to their convictions.

It was not an easy thing to do. Claude and Joyce were loved and respected in Auburntown because they had been the embodiment of the best of the old ways; they had brought sincerity, eloquence, and scholarship to bear on the traditional striving for redemption through Jesus Christ. To tell their congregation that they no longer believed what they had been preaching would be painful, for their parishioners had little basis to accept the new frame of reference. When Claude began confessing the change in his outlook and began preaching on subjects such as racial equality, trade unionism, Christ as a human being with human purposes, they did not stop listening to him but their displeasure was evident. Claude and Joyce began to realize that Auburntown was perhaps not the best parish in which to get their message across.

In early 1930, an opportunity arose to move to a new setting. A colleague at Vanderbilt told Claude and Joyce of an available parish in the mining community of Paris, Arkansas. This was an ideal place for the Williams to develop their new outlook; the parish was in a state of collapse, the church in disrepair, and the local population in desperate economic straits. The material comforts and security that had marked their life in Auburntown, would be gone but they could devote themselves to a community that needed political organization and struggle as much as spiritual guidance.

The situation in Paris proved to be every bit the challenge that the Williams friend had warned. The Presbyterian congregation had been reduced to less than fifteen people and a general air of demoralization and decay marked the entire community. The Depression’s effects were fast making themselves felt, and local community institutions, whether religious or political, had made little provision for the forced idleness and poverty. There was no place for young people to amuse themselves other than a local pool hall (off-limits for the pious). There was no program of private or public relief for the poor, and the local miners faced the crisis of the Depression without a union to defend their interests. The Williams saw immediately that there was no way they could divorce the “salvation of souls” from the salvation of bodies—the only congregation they would have would be the one they could gather through their own efforts.

Their first step was to set up activities which gave the youth of the community opportunities for recreation and self-improvement. With a small parish fund, they purchased athletic equipment, set up a gym in an empty room of the parish house, and organized baseball and basketball leagues. They opened their own collection of books and magazines as a library, organized lecture series on contemporary topics, and stimulated study and discussion groups. Departing even further from the “fundamentalist” path, they began to organize dances at the parish house, explaining to shocked parishioners that young people needed coordinated outlets for sociability.

These activities soon won the Williams a reputation with the working people of the community regardless of denomination. Their house was always full of visitors; the recreational and instructional programs were active and dynamic, and Sunday services packed. The local elders and business leaders did not approve of these activities, but they kept their disapproval relatively private, for the programs had not yet begun to pose a major threat to local political or economic activities.

This atmosphere of toleration began to vanish quickly, however, when Claude and Joyce began to work with local miners who were facing layoffs, wage cuts and outright starvation. A group of miners had come to Claude one day after services and had asked for his help in trying to meet the crisis. Their families were without food; on the occasions when they could find work, they were forced to work overtime without pay; and the union local they had organized had been allowed to deteriorate by the John L. Lewis machine in the United Mine Workers. Claude readily agreed to give them all the aid at his disposal: a place to meet, help with writing literature, and connections with outside sources of political or financial support. After a series of discussions, he persuaded them to reorganize their local and fight for autono¬my within the UMW.

This was the opportunity to participate in the struggle that Claude had been waiting for. In the three years since leaving Vanderbilt, his vision of the Kingdom of God on Earth had begun to take on increasingly socialist overtones. His exposure to the humanization of Christ in Dr. Taylor’s classes, his contacts with other churchmen possessed by same zeal for reform, his participation in interracial conferences, and his increasingly wide reading on scientific and social topics had, in the context of the Depression, made him more and more radical in his political beliefs. But more importantly, Claude saw these beliefs borne out by the Bible. As he reread the Bible with new eyes, he saw the Son of Man as a revolutionary who was continually identified with the extremest victims of society—the poor, the suffering, the exploited. The same was true of virtually all the Old Testament figures who represented the prophetic impulse, from Moses through Amos and Isaiah. Looked at from this perspective, the Bible read as “the longest continuous record of struggle against oppression that mankind possessed.” Claude saw an almost uncanny continuity between the impulses that brought him to the ministry and his growing commitment to class struggle. His work with the miners seemed to fulfill the religious motivations that had guided his life and to fulfill them in a more organic way than he had ever experienced before. He had brought consistency to his world-view and his actions.

I could not, naturally, conceive what the Kingdom of God on Earth would be. . . . But it was, as I understood by the Bible, to be established by the spirit and strivings of men. Come, Go, Do, Ask, Knock, Strive, Relieve, Free, Heal, House, Clothe, Feed were words of action addressed to man in relation to its accomplishment. Clearly, before man could become qualified and have the privilege of becoming active in this struggle, he must have freedom of speech, press, movement, association and opportunity.

Organized labor, civil rights groups, the Socialist Party, pacific and kindred movements were using these freedoms to relieve, heal, clothe—to obtain economic justice, political equality, racial brotherhood and other democratic objectives — steps toward a truly democratic republic. They were "doing the Will of God.” They were fulfilling Divine Purpose. Religious purpose required that I identify myself with their democratic efforts.

The struggle in which the Williams now plunged rapidly put their new views to the test. Even to hold their own economically the miners had to take on a staggering array of enemies—the mine operators, local business groups and political leaders, and the Lewis machine in the UMW, all of whom seemed in collusion with one another. With the Williams’ help, the union organized a successful strike for recognition in 1932, but found themselves embroiled in a conflict with Arkansas UMW leader Dave Fowler who was following Lewis’ directive to place all mine locals under direct control of the central office. In addition, the miners organized hunger marches and relief drives to try to force the local government to distribute food to their families and provide decent wages on work relief projects. In the mass mobilization that these activities required. Claude’s and Joyce’s church became the focal point—a meeting place, a refuge from repression, a place for study and self-improvement. This was deeply reassuring to the people from religious backgrounds, for the struggle in which they were engaged seemed very different from what their religious heritage prescribed, and Claude’s ability to translate it into religious terms greatly increased their courage and resistance. Claude and Joyce infused the struggle with the atmosphere of a crusade; the people’s struggle for bread and freedom was a direct extension of the Son of Man’s struggle to make the world righteous. With the miners’ help, they drew up plans to build a huge “Proletarian Church and Labor Temple” which would be the embodiment of the unity of the class struggle and true religion, a place where miners and all working people would come to worship, hold meetings, study, and meditate.

Needless to say, the local Presbyterian elders were outraged by the direction their young minister had taken. The mine operators and business people, traditionally the pillars of the church, saw their preacher using the pulpit to organize resistance. to their political and economic influence, and they wrote to the Presbytery demanding that he be removed from his pastorate for “heresy.” As evidence for their claim, they not only referred to his political activities, but his “immoral” social programs—dances, lectures on nudism, family planning, and socialism—and his failure to preach only the “Gospel of Salvation” and the Presbyterian position on the Trinity.

Claude and Joyce tried to combat this effort to depose them from their pastorate. A number of influential religious leaders—including Alva Taylor, Willard Uphaus of the Religion and Labor Federation, and Reinhold Niebuhr—supported Claude’s claim that his activities were fully within the framework of his religious convictions. But the Presbytery, looking both to its sources of financial backing and its image of respectability, removed Claude from his pastorate, claiming their action involved no “condemnations” of his work, but was merely an effort to avoid controversy and division in the parish. The final decree of the Presbyterian General Assembly bespoke their peculiar motivation: “The pastoral relationship between the Rev. Claude Williams and the First Presbyterian Church of Paris, Arkansas, is hereby dissolved on behalf of an influential minority, for the good of the Kingdom of God.” As in the Bible, the institutional church had allied itself on the side of the rulers and the wealthy against the oppressed.

The actions of the Presbytery effectively ended the Williams’ role in the Paris struggle, but it freed them for broader work among the sharecroppers and the unemployed of Arkansas, and strengthened their religious convictions. The Williams needed no church to pursue their religious mission; they believed it would unfold wherever the disinherited were struggling for bread, land and justice.

They had little difficulty in finding places to apply their energies. The state of Arkansas was alive with political and economic struggles in the early Depression: hunger marches, strikes, and the dramatic organization of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) in the Delta region. There was a small but vigorous group of socialists and communists throughout the state—homespun radicals whose acquaintance with Marxist theory was less impressive than their organizational ability and capacity to translate socialist ideas into the local idiom. Claude and Joyce were in close contact with all these people, some from Vanderbilt days, some through the miners’ struggle, and others through their work with the Arkansas Socialist Party and the American Federation of Teachers. In addition, Arkansas had its own labor college, Commonwealth, which sought to play an active role in these emerging class movements, and Claude worked closely with the people there. It was a time of great enthusiasm and expectation, when revolutionary utopias were talked of without embarrassment and strategic viewpoints were debated as though the revolution were “around the corner.” The class militance of the sharecroppers and miners, the growing effectiveness of unionization drives and the erosion of racial barriers in the course of struggles evoked images of a spiral of popular protest leading to the final “people’s victory.” In such a context, acts of personal courage and commitment were routine.

Claude and Joyce chose to move to Fort Smith, an industrial city in western Arkansas, where they immediately became involved with the organization of the unemployed into the Workers Alliance. Wages had been cut in the local work relief projects from 30 cents to 20 cents an hour just at the time when local miners had gone out on strike. In protest, the Workers Alliance began organizing marches and demonstrations. When the Williams’ close friend Horace Bryan was arrested for his role in this activity, Claude and Joyce took the lead in organizing a massive hunger march. As the march proceeded, Claude was seized by local deputies and thrown in jail on a charge of barratry. Joyce protested, “If you take him, take me too!” but was persuaded by Claude to go back to take care of the children. The experience was indicative of the quality of class struggle in Arkansas. While Joyce remained outside with the children, ostracized by neighbors and harassed by local notables, Horace Bryan and Claude were thrown into a cell with a motley array of social outcasts—thieves, drunks, male prostitutes—and were periodically besieged by mobs which threatened to pull them out of jail and lynch them. Ill, deprived of food and proper sanitary facilities, dismayed by cellmates who had lost self-respect, they spent their hours discussing political strategy, Marxism, and the shape of the revolutionary future. Through Horace Bryan, Claude received his first in-depth acquaintance with Marxist ideas, and, Claude says, “the most profound presentation of Marxist thinking he had received to this day.”

When he was finally released after a month’s imprisonment, Claude and Joyce moved to the relative safety of Little Rock, Arkansas’s largest city. There he was commissioned by leaders of the STFU, the Workers Alliance, and friends in the Socialist and Communist Parties to organize a “training school” for black and white leaders of the labor movement in Arkansas. The school was perhaps unique among labor education programs in the Depression because of its explicitly religious orientation: its title was “The New Era School of Social Action and Prophetic Religion.” The orientation was necessitated by the strong religious background of virtually all the participants and the fact that the Bible represented virtually the only framework within which they could make sense of their struggles, their setbacks, and their aspirations. Many of the leaders of the unionization drives were “workaday” preachers—men and women who put in a full week in the field or in the factories, but led congregations on Sunday in ramshackle churches and schoolhouses—people with little or no formal schooling and no clerical certification other than their knowledge of the Bible and their call to preach. Claude’s presentation of the Bible as a “continuous record of revolutionary struggle” spoke directly to their need to see their political activities in religious terms, and provided a context in which they could act creatively to overcome their followers’ fear of “race mixing,” physical repression, and ostracism by the local middle class. As Claude put it:

Our purpose was to give positive leadership training in the principles and practice of brotherhood to the normal and accepted leaders of the people of the rural South. These leaders were the toiling Negro and white preachers, exhorters, deacons and teachers among the mass religious movements, denominations and sects.

The school brought together black and white leaders of this background in a context where they could interact creatively, and the program helped set the stage for the unprecedented interracial unity that was to characterize Arkansas labor struggles. Perhaps the most effective program was one which brought together twenty local leaders (ten black, ten white, men and women) of the STFU, who were to become some of the most effective grassroots leaders of that organization.

The success of the program led Claude’s friends in the STFU, H.L. Mitchell and J.R. Butler, to urge him to take his program “out into the field” in 1936, a year in which the union was organizing its largest cotton pickers’ strike. Claude and Joyce readily accepted, although their activities had to take place in the midst of terror. Driving in the dead of night, crawling through fields and swamps, meeting in the cabins of black and white sharecroppers with the threat of lynching hanging over their heads, Claude and Joyce told people about the union and the strike, and likened the people’s struggle to the Biblical figures they knew so well: Moses and the children of Israel laboring under Pharoah’s lash. The strike spread, but the risks for the Williams grew. In late 1936, Claude was caught by a group of planters, beaten and flogged, and sent out of eastern Arkansas with the warning that he would be lynched if he returned.

In 1937, Claude, still deeply involved with field organizing of the STFU, was offered the directorship of Commonwealth College. That institution, founded by utopian socialists in the 1920’s, had been beset with difficulties since it began to participate actively in labor struggles in the Depression most notably, the opposition of the Arkansas state legislature and the conservative wing (AFL) of the Arkansas labor movement. Claude hoped that he could save the college, but found that “Socialist-Communist rivalries” in Arkansas, which he had never taken very seriously, had escalated to the point where they presented almost as much a problem to the College as the opposition of the right. Although it was a non-partisan institution, Commonwealth had become the target of a growing anti-Communist attitude among socialists as well as reactionaries. It refused to purge Communists from its faculty and student body. By taking the Commonwealth directorship, Claude found himself classified in the “communist camp” by his old friends in the Socialist Party and the STFU. National leaders of the Socialist Party and moderate union leaders with whom the STFU was allied in local legislative programs warned Mitchell and Butler that Claude was “dangerous” and that his associations with Commonwealth made him someone who “could not be trusted.”

These tensions came to a head when the STFU had to decide whether it wished to affiliate with the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packinghouse and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), a new CIO union aimed at coordinating agricultural and food processing workers across the country. The union was headed by an avowed Communist and former college professor, Donald Henderson, who knew little about communicating with rural workers and even less about the South. At one point he had advocated dividing both the STFU and the Alabama Sharecroppers Union into three separate unions—one for wage workers, one for tenants, and one for small farmers—a position that had not endeared him to those organizing in southern agriculture. But in spite of Henderson’s weaknesses, the UCAPAWA represented the only chance to join up with the CIO, the most dynamic radical force on the American scene, and for that reason most of the membership, including Claude, supported affiliation.

What followed was a political nightmare. The STFU affiliated, as it were, “under protest,” its controlling group convinced that they were facing a Communist plot to subvert the organization. These fears were fed by national leaders of the Socialist Party, who looked upon the STFU as “their baby” and were jealous of any relationship which would diminish their influence. When the UCAPAWA moved to place the STFU under tight international control and fit it within a trade union framework, the STFU’s Memphis office saw their “movement” going down the drain. The resulting power struggle succeeded in diverting enormous energies from the struggle in the field. The two union cliques spent far more time maneuvering for position than organizing strikes, developing local leadership and trying to stabilize the union organization.

During this power struggle, Claude tried to push a campaign to expand and stabilize the organization, to recruit new members, initiate new actions, and struggle for written contracts. But in the existing climate of hysteria, Claude’s old friends in the Memphis office were unable to see his actions, and those of other rank and file leaders, as anything but efforts to subvert the union. Although Claude had no respect for Henderson, he was committed to maintaining a tie with the CIO, and categorically refused to “red-bait” the UCAPAWA. To the Socialist Party group which had organized the STFU and still controlled it, this was tantamount to being a communist.

The fratricidal atmosphere escalated further in 1938 when J.R. Butler, the STFU president and a close personal friend of the Williams, accidentally found a “document” in Claude’s coat pocket allegedly describing plans to establish a strong Communist Party base in the STFU through Claude and Commonwealth College. Butler immediately released the document to the press and called for Claude to resign from the Executive Board of the STFU, but later changed his mind and agreed not to bring charges. However, on the insistence of Howard Kester, the union leadership decided to put Claude on public trial by the Executive Committee. At a very confused public hearing at which little if anything was clarified, Claude was expelled, along with two other Executive Board members, E.B. McKinney and W.L. Blackstone. Claude tried to organize a resistance to the expulsions. He and McKinney took their cause to the membership, drew up a ten-point program for the reformation and democratization of the union, and won considerable support for their cause among the rank and file, most of whom were dismayed by the absence of concrete organizing activity and the defection from the CIO. But Claude was able to find little support for his efforts outside of the union membership. When the Memphis leadership organized a convention at Cotton Plant, Arkansas, to ratify the Executive Board’s expulsions, Claude received no support from Henderson or any of the UCAPAWA leaders. Grieved, Claude returned to Commonwealth, where he could watch from a distance while the Memphis group and Henderson fought for control of the organization while the membership became more and more disillusioned and demoralized.

At Commonwealth, Claude found himself facing a crisis of a different kind. That institution, after 15 years of effort to provide a communal context for workers’ education in the South, came under direct attack from the Arkansas legislature and local law enforcement officials. Claude had tried to give the college a non-partisan image, but the publicity accorded his expulsion from the STFU negated that effort. Equally important, the problems of administration failed to bring the kind of personal satisfaction he experienced as a preacher, a teacher and an agitator. He concluded that the position at Commonwealth required someone of a different temperment, and he remained as director only in an honorary capacity.

The setbacks that Claude experienced in the STFU and at Commonwealth were bitter, but they did not leave Claude with either a sense of political demoralization or personal defeat. Surveying his experiences from the time he left Paris to his resignation from Commonwealth, he realized that in spite of his defeats—his loss of the Paris pastorate, his expulsion from the STFU, his failure to halt the attacks on Commonwealth—his experiences with the rank and file southern worker and sharecropper had been consistently positive and inspiring. Factional conflicts and repression had not hampered his ability to communicate with people at the grassroots level in the Miners Union and the STFU; they had always stood by him no matter what political opponents said about his work. In the STFU particularly, Claude had remained close to the best rank and file organizers that the union had recruited: O.H. Whitfield, E.B. McKinney, Leon Turner, and W.L. Blackstone. When Claude was expelled, they had tried to help him reform the organization.

Claude concluded that this effectiveness in the field was due to his ability to translate trade union and egalitarian concepts into the medium of evangelical religion. In his last days at Commonwealth, he decided to formalize this approach into an organization which would aid the CIO and civil rights groups in their efforts to organize the South. He set up the “People’s Institute of Applied Religion,’’ a non-sectarian religious organization which would train leaders of the mass religious groups to serve as labor organizers and leaders of struggles against the poll tax, racial discrimination and other repressive features of the southern social order. Claude wrote:

I realized that to preach the Good News of freedom, peace, security and personal dignity, to preach these things to the poor, an army of new preachers to the poor was needed, and that to apply the teachings of the Gospel of the Kingdom to the problems of the here and now, a truly nonsectarian, wholly independent religious, movement was necessary. The People’s Institute of Applied Religion was therefore developed to enlist, train, select and inspire leaders from the people to preach and practice the Gospel of the Kingdom of God on Earth.

The ideological basis for this movement lay in Claude’s interpretation of the Bible as a record of an historic struggle against oppression. But Claude also sensed the necessity to make these views concrete on a non-verbal level. Although the people he was approaching responded to preaching, most of them could not read the conventional written propaganda that the organizers handed out—pamphlets, books and magazines did not reach them. Concepts of class struggle, labor solidarity, and racial brotherhood had to be presented on a symbolic level that people could see. Claude sat down with an artist friend and drew up a series of charts and posters to spell out pictorially the biblical message that he so often preached. Adorned with titles like “The Galilean and the Common People,” “The Nazarene,” and “The Blood of All Nations,” the charts presented biblical scenes which had a revolutionary content, or presented contemporary scenes of struggle underlined by appropriate biblical passages. When he finished, Claude supplied rank and file leaders with copies of these charts. One of the most enthusiastic responses to the new program came from O.H. Whitfield, a black sharecropper-preacher who had been one of the most effective leaders of the STFU and had won national recognition for his role in the Missouri Roadside Demonstration.

Whitfield used the charts in his organizing and became a member of the Board of the People’s Institute. Other preachers with whom Claude had worked displayed equal enthusiasm. He seemed to have hit upon an approach which could convert the southern workingman’s religiosity—the bane of secular minded unionists and radicals—into a positive force for democracy.

To get the new organization off the ground, Claude appealed to his old friends in the Religion and Labor Foundation, Harry F. Ward and Willard Uphaus, and his old mentor Alva Taylor. Despite all the rumblings that the STFU affair had produced about Claude’s communist leanings, these individuals stood by Claude and helped raise sufficient money to print up the charts and provide Claude and Joyce with living expenses.

At first the organization functioned primarily among sharecroppers and tenant farmers in eastern Arkansas and Missouri. But in 1941, Claude was asked by Donald Henderson to run a series of institutes in Memphis to help the UCAPAWA in its organizing drive in the food processing plants of that city.

At that time Memphis was the prisoner of the notorious Boss Crump machine, which kept control of City Hall with a judicious combination of police terror, bribery and political favors. The small AFL crafts council was part of the Crump apparatus, and the CIO had been warned not to try to organize in the town.

In churches, homes and union halls, Claude and his associates held meetings with black and white workers that made prominent use of the People’s Institute charts. The two main union organizers, Harry Koger, a white former YMCA secretary, and O.H. Whitfield made remarkable progress enrolling previously terrorized workers into the UCAPAWA. At meetings filled with prayers, hymns and traditional spirituals converted into union songs, the workers revealed an unexpected determination to stick together in spite of jailings, beatings and efforts to incite racial divisions. The union campaign was hit with the full force of police repression. Claude was arrested, kept overnight, and then released, but was warned that if he didn’t leave town quickly, he would be killed. He thereupon moved his family to Evansville, Indiana, at the geographic top of the “pyramid of cotton production,” where he could maintain offices and a home in safety. The union campaign continued until the CIO was established in many of the city’s industries. A letter from Owen Whitfield to Claude describes some of the techniques used:

WELL! I have my charts on the wall here in the hall and teach from them four times a week to four groups of workers from different plants. There are always ten [10] to fifteen [15] working preachers of different sects, and no end of church officers in the meetings. OH! if our sponsors could see how the common preachers and common people respond to what they call these “GOSPEL FEASTS” and how they rush up and shake hands and give thanks, and invite me to come to their churches. I have visited several of them.

After the success of the Institute’s program in Memphis, Claude and Joyce’s reputation among southern labor organizers and progressive religious leaders grew steadily. They remained in close contact with both the UCAPAWA organizers and the sharecropper preachers they had worked with in Arkansas and Missouri, but in addition organized a series of conferences which presented the Institute’s program to union leaders, ministers and teachers who were involved in building the CIO and in mobilizing support for the American role in World War II. The wartime period brought together a broad “Anti-Fascist Coalition” of the left and center which saw the struggle against Hitler and the struggle for democracy in America as one and the same. To this group the South represented both the greatest obstacle to the democratization of American society and the greatest potential area for its realization. Claude’s ability to reach the southern working man thus assumed a particular importance to many liberals and progressives during the war.

The significance of the Institute’s work was further dramatized by the rise of proto-fascist demagogues and the consolidation of anti-New Deal forces in Congress. After Roosevelt’s unsuccessful campaign to elect liberal candidates in the southern Democratic primaries of 1938, the southern Congressional delegation had allied itself with the Republicans to systematically dismantle New Deal social programs. These congressional leaders, led by such demagogues as Theodore Bilbo and Rankin of Mississippi were often in close alliance with religious demagogues who used evangelical methods and imagery to support segregation and anti-semitism, and to oppose CIO unionization drives. Such agitators as Gerald Smith, Gerald Winrod, and J. Frank Norris used the pulpit to proclaim that the United States was a white Christian nation that had to be protected from the growing influence of Jews and Negroes. These preachers directed their greatest efforts to the ecstatic religious sects, and Claude represented virtually the only person on the left who was trying to present an alternative message to this constituency. In a pamphlet called the “Scriptural Heritage of the People,” Claude presented the rationale for a campaign to appeal to the democratic elements in the religious heritage of the southern working people.

The South today is the most vulnerable section of the country. It is the largest single section where reactionary forces can effectively concentrate. . . . Historically, this section has been populated for the most part by under-fed, uneducated, small farmers, renters, sharecroppers, agricultural day laborers and by impoverished and uncritical industrial workers. . . . [Their understanding] and their reaction might be summarized as follows —

(a) They saw the people in the towns and cities with good “store-bought” clothes. They themselves could not have good clothes. . . . Therefore good clothing came to represent style, worldliness and evil. They rationalized “I’d rather be a door-keeper in the house of the Lord than to dwell in King’s palaces.” [Psalms 84:10)

(b) They were denied the privilege of schools. They saw the people in the towns and cities with from eighth grade to college education . . . who snubbed them, discriminated against them, exploited them and dealt shadily with them. Education became “worldly larnin’.” It was man’s work. The Bible was God’s work. They rationalized “We’ll speak where the Bible speaks and keep silent where the Bible is silent.” (Romans 3:3, 4)

(c) They were denied medical attention. They could only heal by faith in as much as they were or were not healed. Therefore Doctors became evil. They rationalized “We’ll go to the great physician, to Him who can not only heal the soul but the body also. (James 5:14-16)

(e) They could not enjoy civic responsibility because of the poll tax requirements. . . . Therefore, the state became evil, ruled over by the gods of this world. (Ephesians 2:2-3) They sang “We are strangers and pilgrims here seeking the city to come.” (Hebrews 11:10-13)

In the light of their economic conditions and understanding, their only hope of possessing a home was a “home above.” Their only hope of a better world was the personal return of Jesus in the clouds. (I Thessalonians 4:16-18)

.... By these prejudices and the use being made of them by native fascist demagogues, we may be warned of the menacing proto-fascist content in this movement. But on the other hand, we may be challenged, paradoxically enough, by the fact that in this mass religious movement, there is one of the most terrific mass democratic dynamics in America. It is a mass protest against all things economically and culturally unattainable. It is not as yet a conscious economic protest. But it is a conscious religious protest! By a penetrating instinct and an unsophisticated realism, they sense the emptiness, the shamness, artificiality and hypocrisy of our formal religious services. (Matthew 15:8-9) These are truly hungering and thirsting after righteousness. (Matthew 5:6) Here is the field for a new dynamic evangelism in terms of our religio-democratic heritage as contained in THE BOOK. Herein is heard the present day Macedonian call. (Acts 16:9)

With this frame of analysis, Claude and Joyce sought to expand the Institute’s activities throughout the South. He asked his correspondents to report on proto-fascist agitation and, where possible, to help convert preachers in the mass religious sects to a democratic orientation. In several instances, preachers who were members of the Klan embraced the Institute’s program and were able to provide continuing reports on Klan activities to the organization. The Institute continued to aid labor organization in the South as well, providing an effective complement to the union’s traditional “bread and butter appeal.’’

In 1943, Claude and the Institute were presented with an even greater challenge, a position as “minister to labor’’ with the Presbytery of Detroit. Wartime Detroit, the “arsenal of democracy” was filled with recently migrated black and white Southerners who rubbed shoulders together in uneasy juxtaposition in the plants, the streetcars, the parks and recreational areas. Racial tensions in the city posed a threat both to the newly organized industrial unions and to the efficiency of war production. J. Frank Norris and Gerald L.K. Smith drew huge crowds in the white neighborhoods, and nationalist organizations such as the Pacific League flourished among the blacks. The divisions were encouraged by industrial leaders such as Henry Ford, who hired preachers from the ecstatic sects to work in his plants in the hope that they would discourage loyalty to the unions and support the company’s position in negotiations.

Arriving in Detroit, Claude and Joyce brought together a group of union leaders and ministers to make plans to combat the “offensive” of proto-fascist leaders and company officials—publicizing the plans and programs of the agitators and exposing their disruptive impact on war production and morale. An equally important part of the program was enlisting preachers in the plants and training them in the Institute’s methods to counter the anti-union and anti-black propaganda. A team of “shop preachers,” led by John Miles and Virgil Vandenburg, coordinated the program.

The research work of Claude and his associates enabled them to virtually “predict” the Detroit riot of 1943—where it would start, who would participate, and what course it would take. Their understanding of the social dynamics in the white and black neighborhoods enabled them to move quickly into action after the riot to prevent the antagonisms from destroying the unions. With the strong support of labor leaders, educators, clergymen and liberal politicians, the Institute was able to significantly contribute to the narrow thread of racial tolerance that held Detroit together through the rest of the War.

• • • •

EPILOGUE

My story of the Williams’ work must abruptly end here. This piece is part of an introduction to a proposed book of documents and taped interviews dealing with the Williams’ work in the southern movement, and there is much more to speak about than I am now prepared to describe. The Williams returned to the South after World War II to continue the work of the People’s Institute and were able to function openly until the early 50’s when the Institute, like most progressive organizations in the Deep South, was driven underground. Throughout the Fifties, the Williams’ activities were confined to community service programs among their neighbors in Shelby County, Alabama, and they narrowly escaped assassination several times.

The civil rights movement gave the Williams a new opportunity to do open political work. They were active in voter registration drives in Bessemer and Birmingham, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, the formation of the New Democratic Party of Alabama, and the emergence of the peace movement and the student movement in the South. They are still active politically in Birmingham, and remain convinced that the “Scriptural Heritage of the People” can be made into a force for democracy rather than reaction.

Tags

Mark Naison

Mark Naison was a varsity athlete in college; he now teaches at Fordham University and writes on sports for In These Times. (1979)

Mark Naison teaches Afro-American Studies at Fordham University in New York, and is an editor of Radical America. His research on southern radicalism led him to the Williams, with whome he has worked closely for the last three years. (1974)