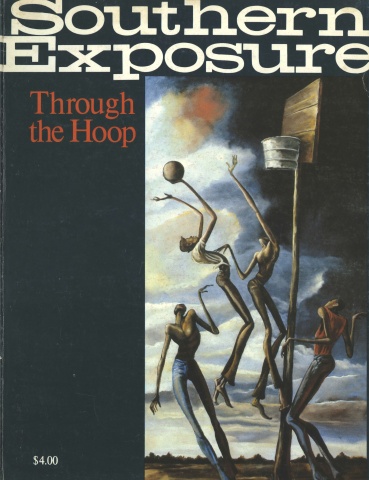

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

ONLY GRAVEYARD OF ITS KIND IN THE WORLD, the sign says. I already knew that, and Amos Powers knew it, and just about everybody in Franklin County, Alabama, knew it. They put the sign up, Amos explained, “for to tell the public.” That’s fair. The public has a right to know when it stumbles onto anything that is “the onliest one of its kind in the world.” But Key Underwood Memorial Park, deep in the Oak-Hickory-Pine forest wilderness of Tennessee Valley, Alabama, at a site formerly called Nancy’s Old Wash Place, is hardly the kind of spot sightseers and tourists accidentally bump into.

Some of the markers are simple, a painted wooden cross with REST IN PEACE. Some are concrete, lettered with a strong finger before the mix hardened. Others are marble, with sandblasted dates reading JUNE 11, 1940 - AUG. 17, 1964. Some have relief carvings on the face or the top of the stones, or laminated photographs. And there is one granite marker, with a bronze plaque that says, OWNER GRANT WHEELER, B’HAM, ALA.

These markers cost from a few dollars to probably $400. Commemorating them all is a monument said to have cost $5,000, “cut by one of them boys over there at Rockwood — Rockwood, Alabama,” and donated by the Tennessee Valley Coon Hunter’s Club. Erected in 1962, the milk-white statue shows two dogs treeing a coon.

There are no bumper stickers or fancy signs pointing the way to the Park. The cemetery is nestled deep in the wilderness of the hills on purpose, and anybody who would make a pilgrimage must first find a Valley resident to vouch for him, to lead the way into the hidden place. I was shown the way by Amos Powers, who owns and operates Vina Sundries, a grocery-drug-toys-drygoods-hardware store.

“A world of people stop off at that park,” Amos said, but we met no traffic. He stopped twice for directions himself before coming to the dirt road he remembered. When we arrived, seven or eight cars full of folks were already there, and Amos went among them, paving my way, and soon introduced me to John Nance. Though he now lives in Ohatchee, Alabama, John was born and raised in Franklin County 67 years ago and had hunted with many of the dogs buried at the cemetery. “There’s Red and there’s Queen,” he pointed out. “I’ve hunted with that dog right there, Troop. He was a c-o-l-d trailer, boy, I’m telling you. He’d trail one that’d been gone along for a long time. He’d pick it up and just walk here and yonder and. . . .”

What’s clear every time someone begins talking about their particular dog is this: coon dogs are work dogs. The relationship of owner to dog is a professional one before it’s a personal one. The dogs have to perform before they earn affection. If Old Blue quits easily, occasionally tracks a rabbit or possum, or barks at the foot of a tree that is coon-empty — he gets kicked, swatted, cussed at (maybe even shot) and then sold, traded or given away. Barking up an empty tree is called, appropriately, lying. And everybody hates a lying coon dog.

“This feller,” John told me, pointing to a grave, “he was a big coon hunter. And he heard about a feller having a monkey who could take his pistol and go up a tree and shoot a coon out, you know. And they’d save cutting the timber and everything. And this feller got awful interested in that monkey, and he called the guy and asked him would he bring his monkey and go coon hunting with him. And he said yeah. So they went, and the dogs treed, and he give his monkey the pistol. He climbed the tree and went up there and POP! Out rolled the coon. They got him and went on, and this feller he was s-o-o-o interested in that monkey. Did he want to sell him?

“Feller told him he’d sell it to him. He said, ‘Will you guarantee that monkey to go up every tree that a dog trees up and shoot the coon out?’ Says, ‘Yes sir, I’ll guarantee you.’ Well, he bought him. He went up, went a-coon hunting that night with him, you know, and carried the monkey. And the dog treed, and he handed him his pistol, and up that tree that monkey went. Stayed about 10 minutes. He come down, walked down with this pistol in his hand, and shot this feller’s dog. So this feller called the guy he bought the monkey from and told him. He said, ‘That damn monkey!’ He said, ‘I carried him out and the dog treed.’ Said, ‘He climbed that tree and went about 10 minutes up there and come down and shot my coon dog.’ Other feller said, ‘Oh. I forgot to tell you about that.’ Said, ‘That monkey just hates a damn lying coon dog!’”

A simple hand-painted sign marks one of the special sites in the graveyard: “TROOP,” FIRST DOG LAID TO REST HERE SEPT. 4, 1937. “When I was hunting with ole Troop,” John Nance recalled, “H. E. Files owned him. He’d bought him from Tom Hall. And H. E. Files said that feller cried when he bought Troop from that feller, from Tom Hall, H. E. and Ben Devaney went over there and went a-hunting with Tom and Troop, and the ole dog struck one of them cold coons. Took him about four or five hours, but he treed him. And H. E. Files said, ‘Tom, would you sell that dog?’ He said, ‘No, I don’t want to sell him a-tall.’ H. E. said, ‘Well, you would sell him, wouldn’t you?’ Tom said, ‘Yeah, I’d take two hundred dollars for him if anybody had little enough sense to give it.’ That was back when two hundred dollars was about like a thousand now. H. E. counted him out two hundred dollars. Led Troop home. Tom Hall cried, and he made H. E. promise then that he’d let him have him back if he ever wanted to get shed of him.”

Apparently Files never did. The two traveled together for six years, staying in the woods for days and sometimes weeks at a time, until the revenuers found Files’ place of business. H. E. went to the pen, and Troop was pawned to Dr. Key Underwood of Tuscumbia for $75. Files bought him back after he served his prison sentence, so he could keep his promise and return Troop to Tom Hall.

“And Key requested that when Troop died he wanted him. He was gonna mount his hide, you know. So Tom told him he’d let him have him, and bout a year after that the hair went to coming off of him. He was old — bout 13, I believe. So Tom Hall gave him back to Key Underwood. Key didn’t want to kill him, or put him to sleep or something. So all the hair come off of him and he couldn’t mount him. And when he died, why he brought him over here and buried him. Key’s the one donated the land.”

There’s a special story attached to this particular place — one that has to do with Troop and a near-legendary Supercoon. “They’d been running this coon, you see,” John told me. “Lot of coon hunters had dogs down here, and they’d run em down to Rock Creek. That coon’d come down by the creek, and that’s as far as they could get him. And the dogs’d hunt and wear themselves down, and the hunt’d be over. And they got where they’d go around here, because it’d ruin their night’s hunt. They didn’t want to strike that coon.

“Key Underwood told em he was gonna catch this coon — he had a dog that’d tree him. So they come over here, and they was all laughing, and he said I want ole Troop to strike him now, y’all keep your dogs tied til Troop strikes. And they turned loose right here on the hill of this branch, and ole Troop struck him. Run him right into Rock Creek, right down where they’d always lose him, you know, like he flew away. And the rest of the dogs all hunted for an hour or two for him and never could find him. But Troop never did quit. He just kept going up and down the creek, up and down the creek. And next morning at four o’clock Troop found him. There’s an old log that was stuck up out of a little old island out there, and that damn coon would swim under water and climb up and get in that log, and that’s where he’d go on em every time. And Troop found him, four o’clock the next morning. That’s the reason Key Underwood brought him here to the head of this branch and buried him here.”

Below the park, behind the concrete picnic tables and a few hundred feet down the hill in the back, the crystal clear spring that furnished water for Nancy’s Old Wash Place and hiding places for Depression coons still runs aimlessly and lazily around the hills. Folks who like their whiskey, I was told, find this a good place to take a swallow. “They say ain’t nothing better’n the world than whiskey and that branch water.”

It was here that John Nance told me about the role hunting played in his life. “It’s changed up so much, these roads and everything, and all that clearing back in here. I’ve walked from Pleasant Site over in through here coon hunting at night, where I could get in the next day sometime, you know. Boy, I recall them days.”

He laughed and shook his head. “Can’t do it now, can’t make it. I quit, gave up all my dogs. I deer hunt. All my best deer dogs, we was out there and somebody stole em where we run a deer across the river. And I just quit having dogs. I still hunt deer, turkey. Didn’t get one this time. Year before last I got two good gobblers with one shot. I called and didn’t even hear a turkey gobble or nothing, but I called.

Thought I might get an answer. And I sat there a good little bit. Always when I call, I sit there long enough that one might come on in. I’ve had em do that and never gobble and come in. And I’ll be durned if there wasn’t five in one drove come up to me, and they walked up as far as the edge of the woods right there, and two of em got right together and stuck their heads up, and I shot and got both of em. There was three more and I could have killed another one, but I wouldn’t do it. I seen I killed both of em. Oh, that’s my ruin. . . . I’ve hunted. . . .”

He shook his head for all he’d hunted and whispered, “God-a-mighty.”

Tags

Jim Salem

Jim Salem teaches American Studies at the University of Alabama, and has authored numerous plays, songs, reference books and non-fiction articles. (1979)