This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 1, "America's Best Music and More..." Find more from that issue here.

Our freckled faces sparkled then like diamonds in the rough

With smiles that smelled of snaggle teeth and good ole garrett snuff

If I could I would be trading all the fatback for the lean

When Jesus was our Savior, and cotton was our king.

(Billy Joe Shaver, Return Music Inc.)

I grew up listening to Minnie Pearl’s “Howdy” and knew in my mind what her hat with its dangling price tag looked like long before I saw her in person. Back then she had a bantering sidekick named Rod Brasfield who came from Hohenwald, Tennessee, and talked about the “Snip, Snap and Bite Cafe.” We used to pass through Hohenwald on the way to the big city of Nashville, and I’d always crane my neck to see the inconspicuous store-front cafe that I considered a major landmark. Down the road apiece off to the left there was a sign pointing the way to Grinder’s Switch, Minnie’s home crossroads. I always found these tangible evidences of Rod and Minnie’s life reassuring, and they reinforced my assumption that the Opry was one of those things in life you take for granted.

Those were the days when June Carter was appearing on the Opry in pantaloons, when Ernest Tubb and Hank Snow were the big stars, when Martha Carson was belting out the gospel and Kitty Wells was stirring my latent-liberated soul by replying that “It Wasn’t God who Made Honky Tonk Angels.” Those were also the days when my cousins who went to the “county” schools got to go on an overnight trip to the Opry for their eighth grade school trip. I went to the “town” school and only got to go to Shiloh National Military Park. I had also been taken to Shiloh on my 5th, 6th and 7th grade trips, so I knew I was getting cheated. I would come home with a dime replica of the confederate flag and my cousins would come home with a picture book full of Opry stars.

Eventually, I came to believe that going to the town school had its benefits, and I left Minnie and all the other Opry stars behind about the same time that I figured out that country music was hillbilly, i.e., redneck, poor, unsophisticated, and most of all, unpopular. It was roughly about the same time I figured out that my ticket off of that West Tennessee farm was a college degree.

I made it off the farm, got a relatively useless degree, and turned my attention to politics and Bob Dylan. Lately, though, I’ve been discovering that a lot of the things I gave up are coming back in style—like farms, Jesus, and country music. My memories of farm life are not the kind that lead me to stand in line for the back to the land movement, and I still have a hard time separating Jesus from his institutional structures. But lately, I’ve been returning to country music like a homing pigeon.

Me and thousands of others. Far from being hillbilly, country music is now the in-thing. Rock stars like Leon Russell (Hank Wilson) and John Fogerty are producing country albums; bluegrass festivals are overrun with longhairs; and country has come to the Las Vegas strip and Max’s Kansas City in New York.

The ascension of country music to such prominent status has been a long, slow climb. For years, the city of Nashville ignored it, and then moved on to outright snobbishness. “You could almost feel the people draw back when you said you were a country performer,“ is the way one veteran described it. Roy Acuff, the “King of Country Music" who recently engaged in some yoyoing antics on the new Opry House stage with President Nixon entered politics in the early 40’s when the governor of the state remarked that he “was disgracing the state by making Nashville the hillbilly capital of the world.”1 It wasn’t until the mid-sixties that Nashville. reluctantly abandoned the elusive image of “the Athens of the South,” and began to come to terms with its second largest growth industry—music.

They’re gonna tear down the Grand Ole Opry

They’re gonna tear down the sound that goes around our song

They’re gonna tear down the Grand Ole Opry.

Another good thing has done gone on, done gone on.

(John Hartford, Robert Taylor, Glaser Publ., Inc.)

Nashville is a funky old town that stretches out along both sides of the Cumberland River. Slower to develop a new concrete and steel façade than most other cities, it is now a combination of worn-out shabby houses, stretches of debris-covered land left by the recent onslaught of urban renewal bulldozers, and an increasing number of shiny new office buildings. Crisscrossing the city is a network of superhighways connecting it with other large southern cities and points north.

On Music Row in particular, the newness is taking over. The major recording studios of Columbia, RCA, and MCA (formerly Decca) now dominate the “Row,” which is headed by the Country Music Hall of Fame. Interspersed with the larger structures are the smaller, remodeled houses which now serve as offices for various publishing companies, talent and booking agencies and small recording studios.

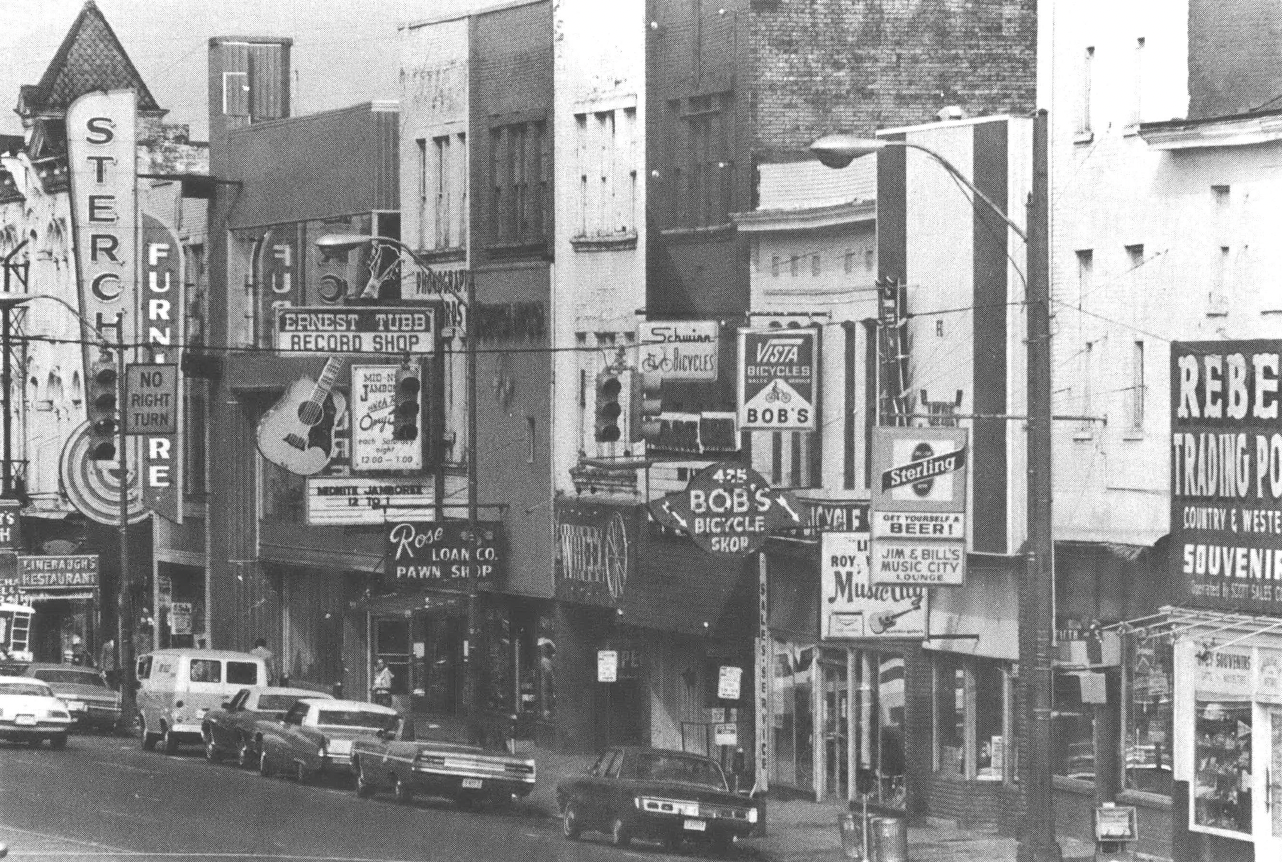

A few blocks away on downtown Broadway, the seedier aspects of the old country music capital are still evident, dominated by the hulk of the Ryman Auditorium, home of the Opry. Until recently crowds continued to line up around the block—reserved seats on one side, general admission on the other.

Ranking next to the Ryman in order of importance and legend is Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, a dark unimpressive hole-in-the-wall which, nevertheless, has a back door directly across the alley from the Opry stage. The walls are covered in photographs, some easily recognizable as Opry stars; others simply the freshly scrubbed faces of Opry-goers who wanted to leave their pictures at Tootsie’s. Those that don’t leave their picture leave their names and occasionally some scrawled message. There is something encouraging about the equality of Tootsie’s; anybody can write their name (magic markers are available behind the bar) or leave their picture on any piece of wall they can find.

Tootsie Bess, the proprietess, watches over the raunchy crowd. She looks like somebody’s grandmother who should be sitting at the head of the table for Sunday-dinner-after-church, but I’ve heard that she actually uses the diamond studded hatpin that Charlie Pride gave her to chase away drunks and stragglers. Other places along the strip have “live” music, but not Tootsie’s. Tootsie’s has a jukebox, and like the walls, about half the names are not recognizable. (“I take the big hits off of the juke box a lot of times. The big guys don’t need it so much because they’ve already got it made.”2) I read somewhere that Willie Nelson was discovered playing the guitar at Tootsie’s while he was half-drunk, and popular history has it that Tom T. Hall and Kris Kristofferson were rather fond of hanging out there and drinking beer while they waited for someone to record the songs they were pitching.

Next door to Tootsie’s is the strip’s newest business establishment, a massage parlor. (Tootsie doesn’t seem to have much competition. I wonder if people write their names and leave their pictures on the walls there.] The rest of the block is taken up by a few souvenir shops, another record store, and a few tacky furniture stores.

Across the street is “live” music at the old Merchant’s Hotel, the Wheel, and the Music City Lounge. All of them have house bands, but no one is too possessive of the microphone; anyone who is really itching to sing or play a few hot licks can easily do so.

Linebaugh’s is tucked in the middle of the block, conveniently close to the Ernest Tubb Record Shop. Open 24 hours a day, Linebaugh’s is the place to hang out and watch for familiar faces. The faces, if not familiar as persons, have familiar looks to match the guitar cases they carry by their side.

No one is quite sure what will happen on Broadway now that the Opry has moved. This particular area will no longer be the focal point for Opry festivities, having been replaced by Opryland’s new amusement park. My suspicions are that at least some of the Opry goers will find their way to Broadway out of nostalgia for the Ryman, and of course, Tootsie’s, Ernest Tubb’s, and Linebaugh’s are landmarks within their own rights.

Out along the Row, the rumblings are of a different kind. Here people speak of “the Industry,” and the Industry is a very hot item at the moment. All together the music industry brings in over $200 million annually to the city of Nashville, and the figure is climbing drastically every year. In 1970 Nashville had 20 recording studios; a recent count put the number at 74. In 1968, some 5500 recording sessions were chalked up; today the number is above 15,000. In addition to the recording studios, the industry includes 29 talent agencies, 750 music publishers, offices for three performing rights organizations, seven trade papers, and seven record pressing plants.

Turn your radio on and listen to the music in the air

Turn your radio on, heaven’s glory share

Turn your lights down low, and listen to the Master’s radio

Get in touch with God, Turn your radio on.

(Albert E. Brumley, Stamps-Baxter Music and Printing Company)

The Opry and the music industry have grown together in Nashville. It all started in 1925 when George D. Hay, the “Solemn Old Judge,” stood in front of a microphone in WSM’s downtown studio and introduced an eighty year old fiddler by the name of Uncle Jimmy Thompson on the WSM Barn Dance. Within a few weeks, the Barn Dance had 25 performers, mostly string bands such as Paul Warmack and the Gully Jumpers, George Wilkerson and his Fruit Jar Drinkers, Arthur Smith and his Dixie Liners, Sam and Kirk McGee, the Delmore Brothers, and Uncle Dave Macon. There was also a Mrs. Klein who played the zither, and the Opry’s one black performer, Deford Bailey on harmonica.3

It was Bailey’s harmonica playing that launched the Opry under its new name. The choice of the name by George Hay was a direct dig at Grand Opera. Hay was waiting in the WSM studio for an NBC network program featuring the New York Symphony to end. In response to a remark by the program announcer about realism in the classics, Hay responded, “You’ve been up in the clouds with Grand Opera, now get down to earth in a four hour shindig of Grand Ole Opry.”

The Opry was an immediate hit with WSM radio listeners, and folks began coming to the studio to watch the show in person. Official Opry history has it that the show was moved when two WSM executives, returning to their offices to work one Saturday night, were not allowed to get inside by an Opry crowd that was on the lookout for linebreakers. The Opry then had successive homes in the Hillsboro Theatre, a large tabernacle in East Nashville, and the old War Memorial Building, where for the first time tickets were sold for 25 cents “to discourage the crowds.”

Finally, in 1941, the Opry moved to its home at the Ryman, an auditorium built originally for the revival meetings of the Rev. Sam Jones by one of his converts, riverboat captain Thomas Ryman. Legend has it that Captain Ryman, who was known for his drinking and gambling, went to the evangelical meeting with the intention of breaking up the meeting, only to be brought to his knees by the good Reverend’s sermon on motherhood. Completed in 1892, the building was used exclusively for religious purposes until 1898, when it was secured by the Confederate Civil War Veterans for their annual reunion—an affair that no doubt was as evangelical in nature as the revivals and certainly matched them in fervor. It was for this meeting that the United Daughters of the Confederacy raised the money and built the Confederate Gallery.4

Later, as Nashville’s city fathers actively pursued the image of the “Athens of the South,” the auditorium was used extensively for classical concerts. But when the Opry made its permanent home there in 1941, the cultured atmosphere began to evaporate in the onslaught of funeral parlor fans of the Last Supper, chewing gum stuck judiciously under the pews, and the general unrefined nature of country fans.

In 1902, C.A. Craig invested in an insurance company on the theory that “unlimited success could be attained by “. . . offering insurance to the lower classes, many with little or no formal education.” Years later, his brother, Edward, who was also one of the original founders of the National Life and Accident Insurance Company, lobbied to begin a radio station because the publicity “the company would gain by use of the radio would help the company’s field men sell insurance to the listeners.” The new station was christened WSM for We Shield Millions and began operations in 1925.

In keeping with their intention to sell insurance to the lower classes, WSM’s prime weapon became the Grand Ole Opry. According to the National Life Corporate Fact Book, “The Opry is probably the most unconventional sales promotion tool ever used by any insurance company. WSM’s radio combination of low frequency and 50,000 watts of clear channel enables it to beam the Opry and the National Life and Accident name every Saturday night into more than 30 states comprising the American heartland. The following week National Life and Accident agents are out knocking on doors identifying their company as ‘the one that puts on the Grand Ole Opry’.” The fact book goes on to say that company officials regard it as a “tremendously valuable sales tool.”5

William Ivey, Director of the Country Music Foundation believes there have been times that the company has been divided over whether or not to keep the Opry. There were periods when the company was divided internally. . . over whether the Opry should be kept because it didn’t always make money. It was not always thriving by any means. Country music didn’t dominate the scene anything like it does now. So, I suspect they were divided on it.6

Those who were in favor of keeping the Opry were on the winning side, and what may have initially paid off only in insurance sales and good public relations has now proved a sound business investment. In March, 1974, the new Opry House opened at Opryland, a $40 million complex that includes an amusement park, the Opry House, and a planned development called Opry Town which will include motels, shops, and a convention center. Just as it was able fifty years ago to effectively project and capitalize on the use of radio to sell its product, the National Life and Accident Insurance Company is demonstrating the same business acumen today in their move toward television. The new Opry House is fully equipped with the latest recording and television facilities. In addition to the main auditorium, there is a smaller television production center behind the main stage for smaller productions. There is some speculation that before too long, there will be a regularly scheduled network show originating from Nashville.

The success of the Opry was important to WSM for selling insurance, but it was also important in establishing Nashville as a recording center. According to William Ivey: I think one of the main functions of WSM is that it provided an almost endless supply of talent to the Nashville music industry, both artists and executives. Fred Rose, who started Acuff-Rose with Roy Acuff, had worked with WSM for awhile as a staff pianist in the 30’s. Jack Stapp, who started Tree Publishing—which had all the Roger Miller songs, and really took off with “Heartbreak Hotel’’—was the Manager of the Grand Ole Opry for a good number of years. Jim Denny, who started Cedarwood Publishing—they have songs like “Daddy Sang Bass’’ and “Detroit City’’— was manager of the Opry. Now, you see this is purely on an executive level. Frances Preston, who was then Frances Williams, was a receptionist for WSM. She is now head of Broadcast Music Inc. [BMI]. You can just go right down the list. I don’t know that WSM was always excited about the fact that they were getting people involved in the music and entertaining business, and then they were leaving to set up their own things, but WSM was very important in that way.7

It was WSM personnel who started Nashville’s first recording studio, Castle Records, in a hotel dining room on Eighth Avenue close to the radio station. According to Aaron Shelton, one of Castle’s founders, “We saw the need for a recording studio because of the great talent the Opry attracted.” But even then, Nashville was looked down on according to Shelton: Artists just weren’t sure it was the thing to do —to record in this little hick town in Tennessee. The big talent would sneak into town, record and leave without anybody knowing it. It took a while for the stars to be sold on Nashville as a recording center. Recording really was an unknown art then. The main thing that attracted the artists was the cooperation of all the people involved . . . the feel that the musicians and engineers had for music . . . something like the personal touch, and maybe more sympathetic treatment of the materials ... or just plain talent.8

The recording industry got a major boost in the early 50’s when Paul Cohen, who was then with Decca Records, guaranteed Owen Bradley one hundred recording sessions a year if he would build a new studio. Bradley had been operating primarily out of a small concrete block structure doing primarily industrial film work, but on the basis of Cohen’s guarantee, he purchased an old duplex on Sixteenth Avenue, South, for a mere $7500. For another $7500 he and his brother, Harold, purchased an old quonset hut and placed it at the back of the duplex. The quonset was used initially for filming commercials and storage, but when the sessions became too large for the house, burlap bags were hung around the walls to absorb the acoustics and the quonset became a recording studio. The first recording session in the makeshift studio produced a smash hit for Decca called “The Battle of New Orleans.”9

Bradley’s studio was the beginning of what is now known as Music Row. Columbia Records purchased the original studio in the 60’s and built a new studio around the quonset hut, and today all the major recording studios are either on the Row or nearby.

As the recording industry began to grow, so did its related industries. Acuff-Rose was the first publishing company to set up in the early 40’s. One of their early recording artists was Hank Williams, the tortured Montgomery blues singer who died at the age of 29 from “too much living, too much sorrow, too much love, too much alcohol and drugs."10 Williams’ impact on the music today is as magical as it was in 1949 when he appeared on the Opry for the first time and was called back for six encores. The story is told that when Hank wanted to record “My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It” Fred Rose thought it was so bad, he walked out of the studio. Williams recorded the song without his A & R man, and Acuff-Rose had another smash hit. Acuff-Rose is still one of the most powerful publishing companies in the city and now has international operations. In addition to Hank Williams, their catalogue includes such notables as Pee Wee King, Charlie and Ira Louvin, Martha Carson, Bill Carlisle, Marty Robbins, Boudleaux Bryant, the Everly Brothers, John D. Loudermilk, Kitty Wells, and Mickey Newberry.

As the industry boomed, new offices continued to open: booking and talent agencies to handle personal appearances for the artists, more publishing companies, record pressing plants, and eventually trade publications. More recently, the impact of the industry has spread to areas unrelated to music. Bill Williams, the Nashville editor of Billboard, estimates that today there are fifty lawyers devoting full time to performing rights whereas several years ago there were only two. One of the most obvious by-products of the recent growth can be seen in the numerous hotels and restaurants sprouting up in the vicinity of Music Row. Another boost has come from the universities; today almost all of them offer courses or seminars related to the music industry.

I bought this rhinestone suit in California

And these boots came all the way from Mexico

This Cadillac ain’t nothing son, you ought to see the greyhound

I bought to take my band from show to show

You’ve seen my face a thousand times on TV

And heard me on your local radio show

And in your eyes, I see the admiration there for me

But son there is something that you ought to know

Well, I’ve got to take a drink to keep from shaking

And motel rooms ain’t nothing like a home

And money can’t make love grow any stronger

When you leave your woman home alone

She can’t raise the children with no daddy

She can’t love a man who’s always gone.

It takes a whole lot more than pride

To keep your feelings locked inside

While you sing another pretty country song

Well, its true I took some pills to stay awake son

And this diamond ring I wear is just for show

And I’ve got a little cabin in the country

When I’m not on the road, that’s where I go

Try and put my feelings down on paper,

Right or wrong the show has to go on

And I cry deep down inside and keep on smiling

While I sing another pretty country song.

(David Allen Coe, Window Music, Inc.)

In the early days of the Opry, instrumental music dominated, particularly the fiddle and banjo, and whatever singing occurred was incidental. This changed, however, when Roy Acuff and his Smokey Mountain Boys came to the Opry in 1938. His renditions of “The Great Speckled Bird” and the “Wabash Cannon Ball” became Opry favorites and Acuff was soon followed by Eddy Arnold (then known as the Tennessee Plowboy), Cowboy Copas, and Ernest Tubb.

The Opry book describes Tubb as having childhood dreams of being a screen cowboy until he heard and admired the records of the late Jimmy Rodgers. H He bought his first guitar for $5.95, began practicing his yodeling in the pasture, and eventually got his own radio program in San Antonio. Tubb joined the Opry in 1943 after his song “I’m Walking the Floor Over You” became a hit. He opened his now famous record store three years later a half a block away from the Ryman. In an interview with Marshall Fallwell on one of the Opry’s final weekends, Tubb reminisced about his own career and his friend, Hank Williams.

Oh, I guess I been everywhere. I still go out on the road about 200 days a year. I figured it out once. Since I began, I’ve averaged about 100,000 miles a year. Back when I started, it was hard travelin’. You see, there weren't no buses or planes like there are now. Another thing, you had to be back in Nashville every Saturday night, come hell or high water, for the Opry. No matter where you were. In the forties, it was rough, too, because of the war. The hardest thing was finding bootleg tires. I wouldn't do anything else though. I had a lot of jobs and I hated them all. During the Depression, I worked all over Texas doing everything from threshing wheat to digging sewer ditches at Randolph Field.

Back in 1949, when I finally got Jim Denny, who was the manager of the Opry, to let Hank Williams come on my show; Hank promised me he wouldn’t drink for six months. He said, “Lord, I'd crawl all the way to Nashville on my stomach if they’d let me be on the Opry. Ernest, if you let me come with you, I’ll never take another drink.’’ I said, “Son, don’t say something you can’t do, but if you quit for six months, I’ll try to get you on the show." Well, not many people know this, but Hank Williams, to my knowledge, didn't take a single drink for nine months. And I know, because he was on my show and I worked closely with him.12

Throughout the 40’s and early 50’s, Nashville continued to grow as the country music capital of the world. Stars like Hank Williams, Martha Carson, Kitty Wells, Marty Robbins, Ferlin Husky, Patsy Cline, Grandpa Jones, Stringbean, Charlie and Ira Louvin, Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters, Webb Pierce, Bill Monroe, Lefty Frizzell and Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs were launched from the Opry stage.

One of the Opry listeners was a young man by the name of Porter Wagoner in West Plains, Missouri. I started off in a grocery store. I worked in the butcher shop and I was a stock boy. The man I worked for knew that I played the guitar and sang so he asked me to bring it down to the store and sing some songs for him. So I did and he liked it and he said he’d like for me to do a 15 minute show on radio from the store each morning early and tell ’em what our specials that day was, you know. So, I started on the air at 6 in the morning. I’d go down and open the store and just when it’d come 6:15 they'd give me a cue and I’d start picking and singing. A bus driver passing through West Plains heard Porter and persuaded the manager of a radio station in Springfield, Missouri, to go down and listen to him. Porter moved to Springfield in 1949 to become a regular on the station, and started recording for RCA Victor one year later.

I started recording in 1950. I never did have a hit for five years. Anymore, of course, if you don’t get a hit with a company within a year, they drop you. But back then there wasn’t that much talent around and they gave me that long. In 1955 I had “Satisfied Mind’’ which was the Song of the Year. That opened many doors to me.

Porter became an Opry regular in 1956—and like many other Opry stars realized one of his greatest ambitions.

Well, we listened to the Grand Ole Opry. I never drearned of getting to come to see it, much less be on it, because it was like a million miles away. I liked all the stars on the Grand Ole Opry— Roy Acuff, Bill Monroe, Ernest Tubb—and then Hank Williams, of course, was an idol of mine. I liked his songs because they all said something, they told a story.

I used to be plowing in the field and I’d pretend I was on the Grand Ole Opry. And I’d emcee and introduce, “Now here’s a great star of country music, ladies and gentlemen, let’s give him a big welcome to our show. ...” I’d be down there by myself in the dust. One day the boy that lived on the farm next to ours—I didn’t know there was anybody in miles—he was standing at the end of the field and he heard me talking to myself, emceeing you know, and he asked me what I was a-doing. And I told him I was practicing, someday I was going to the Grand Ole Opry. He said, yeah, I know you are. You’ll be looking at these mules you’re plowing when you’re 65 if you’re able.13

After going through a major slump in the late fifties and early sixties, when the full impact of rock and roll hit, Nashville began to slide into a period of major growth in the mid-sixties. Chet Atkins, head of RCA Victor in Nashville had always had trouble in the country music business because he wasn’t “country” enough, and had been fired from several radio jobs for that reason. As the Vice-President of RCA Victor and a major country producer, he began to develop a “sound” that was not traditional country, utilizing choral groups, horns, and strings as background in lieu of the traditional country accompaniments of steel guitar, fiddle, and banjo. The result was a sound that enabled many country records to gain popularity in the pop field as well as country.

Word also began to spread about the Nashville Sound that was being generated by the studio sidemen. The Nashville style was to go into a studio, run through a song several times to let everyone get the feel of it, and then put it down on tape. More and more artists began to gravitate toward Nashville in search of relaxed recording sessions. New names were added steadily to the star list during this period. Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, Bill Anderson, Tom T. Hall, Tammy Wynette, Merle Haggard, and many more. Johnny Cash, Conway Twitty and others who left during the slump returned to country.

Today the city is a rich amalgam of its not-so-popular past, and its very-bright-looking future. The entire town is suffused with a sense of growth, excitement, and change—perhaps best symbolized in the opening of the new Opry House. Rhinestone suits, superstars, Cadillacs and custom-made buses are still very much in evidence, co-existing alongside some scroungy looking longhairs who are making the scene as writers, musicians, producers, and record company executives. William Ivey believes that Nashville is still a relaxed and friendly atmosphere, but sees changes coming:

The country music industry is really small-townish and personal, and the big-time show¬ biz paranoia which you see taking over some other segments has not yet taken over Nashville or Bakersfield, or even the country music people in Los Angeles. It still is a community; there is still a feeling you could get all the important country music executives into a medium sized room, and they would all know one another. . . . The super big media business, where you protect yourself with a lot of paper and a lot of contracts, four attorneys between negotiating people and so on, hasn’t yet developed in the country music scene.

It probably will, because country music is very hot right now. It’s coming because it is a natural accompaniment to success. But it is still not present in country music in the degree it is in motion pictures, straight pop music or television, and that is an advantage. That gives Nashville a lot of strength.

I think the people who are running the country music industry are mainly people who started out with nothing, got into country music when there was no status in it of any kind, and no money. So they were in it for the love of the music and love of the other people, and all of a sudden they have become successful. But that is still a secondary thing. They would still be there if things were back where they were in the 40’s and 50’s—no status, no money. Now, maybe the next generation is not going to be that way. The next generation may just be in Country music because it is profitable.

It is changing. Partly because the people who started the industry are reaching retirement age, and it just happened that way you know. Like Chet Atkins, he is not retirement age, but he decided about two years ago to move into more personal things — do a little more playing and less administrative work. He was here in the middle and late 40's, actually when it was just getting started. And Don Law who was a super producer for country stuff for Columbia back in the middle 30’s. He co-produced many of the original Bob Wills sessions. He is semi-retired. Owen Bradley is in his early 60's; he was the head of Decca, which is now MCA, for years and years.

So as this group of people hands over control to the next generation, I suspect there will be some changes.14

The changes are occurring rapidly: an influx of new record labels setting up Nashville division offices with accompanying changes in personnel and style; a “new” audience that is younger, better-educated and wealthier; and an “old” audience that has steadily become more urban and consumer oriented. Purists are apt to dismiss the recent era as '‘commercial,” and while it may be an appropriate adjective, it is an insufficient label. Country music has always reflected the culture from which it comes, and its recent success at the market place is no exception.

Country music today and the country music you heard on the Opry in 1938 is parallel to the difference between the music you heard on the south side of Chicago in 1948 when Muddy Waters and Howlin'Wolf had just come up there from Mississippi and the music you heard in Detroit with Diana Ross and Stevie Wonder and that crowd. It is just what happens when you start to get sophisticated musical minds, and sophisticated songwriters and businessmen involved with a whole tradition. It gets to be this hybrid that takes something from commercial music, from tin pan alley, and also something from the folk tradition.

It’s gained an urban intelligentsia. It’s gained the middle, middle class. But college kids are not a very good audience; they are extremely fickle. They move from fad to fad, and they’ll love bluegrass for a while and drop it and then move on to B.B. King for five years, and then go on to this or that. So I don’t consider that change to be all that important. I don’t think the music will ever play to that audience, and I don’t think that country music has lost or abandoned its traditional audience. That is why I think the new Opry House will succeed.15

Willie, you’re wild as a Texas blue northern

Ready-rolled from the same makings as me

And I reckon we’ll ramble till hell freezes over

Willie the wandering gypsy and me.

(Billy Joe Shaver, Return Music, Inc.)

The new audience cannot be ignored, however, and regardless of how fickle it may eventually turn out to be, it is there now. Its representatives in Nashville are the laidback country cowboys, sometimes referred to as “underground,” third-generation country, or hipbillies.

It’s hard to get at what distinguishes Nashville’s new breed, although surface indications are easy enough—denims and leather as opposed to Nudie’s rhinestoned and sequined suits. Long hair. Beards, sometimes. The more subtle importance of the cowboys is harder to figure. Musically they are closer to, and in the case of Waylon Jennings, come out of—the rockabilly tradition of the mid-fifties, the raunchy gut-country blues that Sun Records was producing in a makeshift studio in Memphis under the tutelage of Sam Phillips. Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, and even Charlie Rich were on the Sun roster, producing hit after hit that let the country know that music wasn’t just for easy listening.

The rockabilly influence was soon put in check, however, as the Nashville sound moved toward strings, horn and choral background provided by the Anita Kerr Singers—not exactly the kind of music to get down and get it on with. Could be, though, that rockabilly is coming back to haunt Music Row in the persons of the cowboys, who, like their early counterparts, are just too successful to be ignored.

It is unclear whether the cowboys take themselves more seriously than the rest of Nashville. One writer, who is definitely not underground, wondered if there wasn’t some “putting on” going on. Others simply shrug and say there is “room for everybody” in Nashville. A few others openly express hostility. Whatever their associates think of them, the underground cowboy image is comfortable for the cowboys themselves. And while there may be room for everybody in the town, the atmosphere around Glaser Recording Studio, the Burger Boy, or just any old pinball machine you can find is definitely more relaxed for most of them.

Willie Nelson is sometimes credited with beginning the irreverent cowboy movement. (Sometimes it’s Kris Kristofferson. Sometimes Mickey Newberry.) Nelson was under contract to RCA Victor for years, produced a number of albums for them, and wrote a good many of Nashville’s hit songs. But as Billy Joe Shaver remarked, “I don’t think they knew what they had a hold of.” Willie Nelson left Nashville and went back to Texas and is now in the center of a whole new blend of music that is seeping out over the Texas border.

The cowboys may be chaffing right now about Nashville’s uneasy acceptance of their music, but it seems likely that their time is at hand. Song¬ writers like Kris Kristofferson, Willie Nelson, Billy Joe Shaver, David Allen Coe, Lee Clayton, Johnny Darrell, Linda Hargrove and Buzz Rabin are becoming increasingly popular within the Nashville scene while people like John Prine, Leon Russell and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and others look to Nashville for influence in their own music.

Hell, I just thought I’d mention my grandma’s old age pension

Is the reason I’m a-standing here today

I got a good Christian raising and an eighth grade education

There ain’t no need in y’all a-treating me this way.

(Billy Joe Shaver, Return Music, Inc.)

Traditionally country music has not strayed from the theme of broken hearts and very discreet cheating—with occasional references to the Bible, Mother, and how hard it is for poor folks to make a living. Regardless of the seeming limitations of the topic, country lyrics have always been direct and to the point—articulating in songs familiar feelings and situations that their audience might otherwise have been hard pressed to find a way to express. The words seldom present the world as pretty; they’re more apt to tell you how bad it is and where you can go for a little comfort.

Dave Hickey, writing in Country Music magazine summed it up well: “.. .lyrically pop songs present the world as it ought to be, as it exists in the dreams of various record executives, and adolescents. Country lyrics, on the other hand, are about the world as it is; they are made by adults for adults—not rich and famous ones, just grown-up people making it from day to day. ... If pop music is about that distance between the stars above and the audience below, then country music, at least for me, is about the community they share.16

One of the shared communities has been the hillbilly ghettoes of the northern industrial cities, where they have gone to make $5 a day on the assembly line when the farms gave out. “Detroit City,” “Streets of Baltimore,” and the more recent “Streets of Chicago” are stories about displaced homesick migrants.

Home folks think I’m big in Detroit City

From the letters that I write they think I’m fine

But by day I make the cars and by night I make the bars

If only they could read between the lines

Oh, how I wanna go home.

(Mel Tillis, Cedarwood Publishing Company)

I sold my farm and took my woman where she wanted to be

We left our farm and all our kin back there in Tennessee

I bought those one-way tickets she had often begged me for

And they took us to the streets of Baltimore.

(Harlan Howard, Tree International Publishers)

Merle Haggard, one of country music’s most successful writer/performers writes hard-hitting songs that have endeared him to blue collar workers all over the country. Although he is often better known for his “Okie From Muskogee” and “Fighting Side of Me,” his songs like “Hungry Eyes,” “Tulare Dust,” and “Mama Tried” are reminiscent of those penned by Woody Guthrie in the 30's.

He dreamed of something better and my mama’s faith was strong

And us kids were just too young to realize

That another class of people kept us somewhere just below

One more reason for my mama’s hungry eyes.

(Merle Haggard, Blue Book Music Corp.)

Johnny Russell’s hit, “Rednecks, Whitesocks and Blue Ribbon Beer” plays on the same theme as “Okie” and “Fighting Side,” but in a less aggressive way. “Rednecks” doesn’t put anyone else down; It is just a proud song about why people stick together:

No, we don’t fit into that white collar crowd

We’re a little too rough, and a little too loud

There’s no place that I’d rather be than right here

With my redneck, whitesocks, and blue ribbon beer.

(Bob McDill, Jack Music, Inc.)

I’ve always been particularly grateful for Dolly Parton’s song “In the Good Old Days (When Times were Bad).” Nostalgia for the good old days and recurring romanticism about poor folks is running rampant, and Dolly’s song is as good an answer as any for those who for some uncanny reason think that being poor and being righteous is the same thing.

We’d get up before sunup to get the work done-up

We’d work in the fields till the sun had gone down

We’ve stood and we’ve cried as we’ve helplessly watched

A hail storm a-beating our crops to the ground

We’ve gone to bed hungry many nights in the past

In the good old days when times were bad.

No amount of money could buy from me

The memories that I have of them

No amount of money could pay me

To go back and live through them again

I’ve seen daddy’s hands break open and bleed

And I’ve seen him work till he’s stiff as a board

And I’ve seen mama lay in sickness and suffering

In need of a doctor we couldn’t afford

Anything at all was more than we had

In the gold old days, when times were bad.

(Dolly Parton, Owepar Publishing Company)

Country lyrics have always implied a strong class consciousness, but its consciousness about race and women is of a different nature. Hillbilly, redneck music is as close to southern black music as are the two communities in a Mississippi delta town, and as far away from acknowledging that closeness as the history of the times. Hank Williams learned to play guitar from an old black man in Montgomery while he helped him shine shoes; Jimmy Rodgers learned to accompany his lonesome yodels by hanging around Negro workers in the railroad yards; and Carl Perkins, the son of a white sharecropper, used to trek across the fields at night to the other side of the plantation to learn to play the guitar from a black sharecropper. Paul Hemphill in his book, The Nashville Sound, notes:

The influence of the Negro on country music has been considerable over the years, for obvious reasons. In the beginning, country music belonged to the poor white rural southerner and “soul” or “blues” belonged to the Negro. Living side by side in the South, their hopes and fears and joys and failures essentially the same, it was natural that they should share musical tastes and borrow from each other.17

But like other things borrowed from the black community, it was carried safely back to the white side of town. When the Opry started, it had one black performer, Deford Bailey, who could play a mean harmonica and was one of the first artists to record on the Victor label. Bailey left the Opry after 15 years: “I wasn’t getting but four or five dollars a night and they kept me standing in the back.” (George Hay referred to him as the Opry “mascot” and “like others of his race, lazy.”)

The blatant kind of racism that characterized country music in earlier years is now as subdued and institutionalized as it is elsewhere in the country. Country Charlie Pride, a black man from Sledge, Mississippi, who grew up listening to the Opry, is one of RCA’s hottest recording stars and plays to packed houses wherever he goes—to white audiences who, if they can afford it, probably send their kids to Christian academies to avoid busing. But Pride is the only black performer to make it in any significant way. The music remains essentially the property of the white community. Perhaps more significant in the long run will be the acceptance of songs like Bobby Goldsboro’s recent hit, which talks about black and white sharecroppers:

Mama never had a flower garden

Cause cotton grew right up to our front door

Daddy never went on a vacation

He died a tired old man at 44

Our neighbors in the big house called us rednecks

Cause we lived in a poor sharecropper’s shack

The Jacksons down the road were poor just like we were

But our skins were white and theirs was black

I believe the South is gonna rise again

But not the way we thought it would back then

I see everybody walking hand in hand

Yes, I believe the South is gonna rise again.

(B. Braddock, Tree Publishing Company).

Kitty Wells gained the title “Queen of Country” in the mid-fifties when her answer to “The Wild Side of Life” called “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” was a big hit. But it was hardly a contest; she was one of the few women singers around. Kitty Wells, Martha Carson, and Wilma Lee Cooper were all overshadowed by their male contemporaries, and it is still difficult even now to track down information on women singers in the early days of country music. Wilma Lee and Stony Cooper remember the reluctance of companies in the early days to record female singers:

Wilma Lee: When we started, there weren’t many women singers in the business at all. Just a few. Back then, they always said they couldn’t sell a woman singer on records.

Stony: Now, there was a woman singer by the name of Cousin Emmy. Terriffic showman. Done well enough singing, and could pick a banjo like Stringbean. Well, Decca tried her, and she did a fantastic job on “Ruby, Are You Mad At Your Man.” But they couldn’t sell it, I never could understand why they couldn't sell women singers in the country field, but they just didn't do it. Now there were very few when Wilma and I started recording; I think I can say there probably wasn’t over five girl singers.18

Eventually, “girl” singers did begin to sell. Kitty Wells hung in there (she had been singing for 15 years before she made it with a hit), and was followed eventually by Patsy Cline, and later Loretta Lynn, Dottie West and Jean Shepherd. Today women are some of Nashville’s biggest superstars.

Although their professional status has improved drastically, the portrayal of women in the lyrics has not. Women are presented in a variety of roles: cheaters (Putting on my makeup/ putting on the one that really loves me); loving wives who passively accept a double standard (I guess someday she knows I’ll come home to stay/ That's why my woman keeps loving her man ); whores (If fingerprints showed up on skin/ wonder whose I’d find on you); lovers (Nobody knows what goes on behind closed doors); flirts (She had ruby red lips, coal black hair/ And eyes that would tempt any man); and mothers (The full cost of my love is no charge). Whether the image presented is that of a loving wife or a whore, the role is always defined within the context of the woman’s relationship to a man. Very seldom do women surface as independent human beings. Again, I think some of Dolly Parton’s songs are exceptional. “Don’t Let It Trouble Your Mind,” “That’s Just the Way I Am,” and “Just Because I’m, a Woman” reflect an independence and spirit that is rare.

Even though you may not understand me

I hope that you’ll accept me like I am

For there are many sides of me

My mind and spirit must be free

I don’t know why, its just the way I am.

I’d rather have you go than stay

And put me down, a-thinking you’re above me

Our love is so wound up, it’s best that we unwind

And if you don’t love me, leave me

And don’t let it trouble your mind.

(Dolly Parton, Owepar Publishing Company)

As more women begin to make it both as writers and performers, the image is bound to change. Linda Hargrove, for example, a young singer/songwriter says, “In my music I try to bring a total picture out ... to see women as more than just useful.”

In the end, however, the changing image of women cannot and should not be left only to women writers. For instance, I really can’t remember Tom T. Hall writing a song that diminishes in any way the people he writes about. “Ravishing Ruby” the truckstop waitress is sketched as gently and lovingly as the kid hitchhiking through Kentucky.)

Willie Nelson’s concept album, Phases and Stages, (Atlantic, SD-7291) devotes one side to the “woman’s side’’ and is very well done.

Washing the dishes, scrubbing the floor

Caring for someone who doesn’t care anymore

Learning to hate all the things that she once loved to do.

After carefully considering the whole situation

And I stand with my back to the wall

Walking is better than running away

And crawling ain’t no good at all.

(Willie Nelson, Willie Nelson Music, Inc.)

Of course, there may be some hope for down¬ right militance. Hidden away on Tanya Tucker’s latest album is a song about Molly Marlow, a woman who is raped when she is young, and gets her revenge years later when as a nurse she either kills or deliberately lets her abductor die.

What a beautiful thought I am thinking

Concerning a Great Speckled Bird

Remember her name is recorded

On the pages of God’s holy word.

Desiring to lower her standards

They watch every move that she makes

They long to find fault with her teachings

But really they find no mistakes.

Yes, of course, country music is changing. It changed when folks began moving off the farms and out of the mountains into the factories and honky tonks of the northern industrial cities; it changed again when Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis uncovered some repressed white country soul; and it changed some more when Johnny Cash and Hee Haw began making it into people’s living rooms on color TV sets. No doubt it will continue to change.

And yes, it is commercial, reflecting as always with painful accuracy the world around it. There was never any legitimate reason to believe that country music should remain a pocket of purity in a plastic environment, or “country” in an urban society. But country music has always had a knack for making bearable the hard times and immortalizing the good. There’s no reason to think now that it can be contained inside the chain link fence at Opryland anymore than it could be contained in the WSM studio in the 30’s. As long as there is the same compelling need for honesty somewhere in our lives, country music will continue to have a growing audience.

Footnotes

1. Robert Shelton, The Country Music Story (Bobbs- Merrill Co., 1966), pp. 81-82.

2. Jerry Thompson, “Tootsie: Funky First Lady of Honky-Tonk,” Country Music magazine, Vol. 2, No. 7 (March, 1974), p. 32.

3. There is some dispute about who the first performer on the Barn Dance was. Other accounts have Dr. Humphrey Bate and his band preceeding Uncle Jimmy Thompson. See “Setting the Opry Record Straight,” Billboard (April 20, 1970), p. N-10.

4. Ibid., p. N-4.

5. “Nashville’s Rich Rob the Roost,” The Real Dirt newspaper, Nashville, Tenn., 1973.

6. Interview with William Ivey, Director of the Country Music Foundation, Nashville, Tennessee, March 5,1974. The Country Music Foundation includes the Country Music Hall of Fame and Library. The Foundation publishes quarterly The Journal of Country Music.

7. Ibid.

8. Billboard, p. N-14.

9. Ibid., p. N-6.

10. Shelton, p. 91.

11. See also Shelton, pp. 55-69.

12. Marshall Fallwell, “E.T. Remembers,” Country Music magazine, Vol. 2, No. 8 (April, 1974), p. 72.

13. Gene Guerrero, “Interview with Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton,” Great Speckled Bird, May, 1971.

14. Ivey Interview.

15. Ibid.

16. Dave Hickey, “Dolly Parton’s Songs Have Real Soul,” Country Music, Vol. 1, No. 6 (February, 1973), pp. 28-29. Hickey consistently writes some of the best articles appearing on country music. His “Growing Up on the Jax Beer Highway” (Country Music, II, 3), isa real delight, and his writing on the Nashville cowboys is so perceptive, it leads you to believe he might be one. See “In Defense of the Telecaster Cowboy Outlaws” and “Billy Joe Shaver: An Overnight Success After Six Years,” Country Music, Vol. 2, No. 5 and No. 2.

17. Paul Hemphill, The Nashville Sound: Bright Lights and Country Music (Simon and Schuster, 1970), p. 109.

18. Interview with Wilma Lee and Stony Cooper, Nashville, Tennessee, March 8, 1974.

In addition to these specific sources, I interviewed several people in Nashville who were particularly helpful: Harlan Howard, Billy Joe Shaver, Tom T. Hall, Paul Tannen (Screen Gems, Inc.), Steve Young, Louise Scruggs, David Allen Coe, and Bud Wendell (general manager of Opry Land). Bill Monroe, Vassar Clements, Loretta Lynn, Natt Stucky, and Johnny Russell were interviewed in Atlanta. Portions of these interviews were published in The Great Speckled Bird during April and May, 1974.

Tags

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)