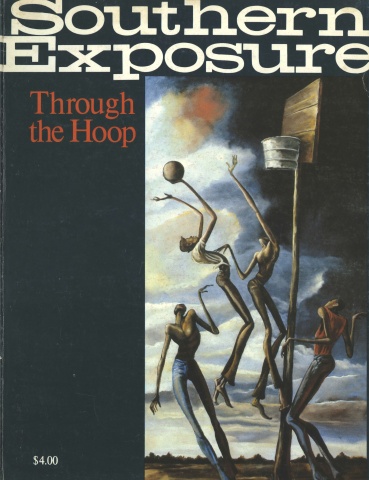

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

There will be no 3000-meter women’s race and no women’s marathon at the 1980 Moscow Olympics. The all-male International Olympic Committee feels 3000 meters is “a little too strenuous for women.” The 87 members must near apoplexy when a 26-mile event is broached. The longest race for women at the Games will remain 1500 meters, less than a mile.

The practice of blackballing women from athletic competition began as early as 776 B.C. During the original Olympics, any woman discovered watching naked Greek males compete was chucked over a cliff. At the first modern Olympics, held in Athens in 1896, a woman named Melpomene requested entry into the marathon. The Olympic Committee declined, and the modern Games’ founder, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, commented, “Women have but one task, that of crowning the winner with garlands.”

Unpersuaded, Melpomene began women’s long-standing custom of jumping into a race welcomed or not. She finished in four hours and 30 minutes.

Thirty-two years later, a limited track program for women was finally included in the 1928 Amsterdam Games. But American women physical educators, in one of many misguided and destructive actions, asked the IOC to omit women’s track from the 1932 Los Angeles Games. The 800-meter race was dropped as a result of their appeal, but nothing else. Although reinstatement was often petitioned, it wasn’t until 1960 that the race returned.

Multimillionaire Avery Brundage, president of the IOC for 20 years, had frequently suggested that women be omitted from the Games altogether — or, if they remained, that their events and sports be reduced, rather than expanded. Before the IOC will even consider allowing a women’s marathon, it wants the race held in 26 participating nations. Jacqueline Hansen, twice former world-record holder in the women’s marathon, pointed out the absurdity of such a demand in a Runner’s World column. In the 1972 Games, she said, only eight countries entered teams in women’s volleyball, six in men’s field, and 16 each in water polo and team handball.

“How many nations participated in the white water canoeing in Munich?” asked Hansen. “How many African and Arab countries, often cast as the villainous objectors to women’s distance running, support the Winter Olympics or yachting? The IOC would appear to feel terribly threatened by the women’s running movement. Perhaps beneath all of the physiological and political arguments lie cultural and psychological problems of male dominance and ego protection.”

Leal-Ann Reinhart, 1977 women’s AAU national marathon champion, wrote a letter with Tom Sturak to Runner’s World about the lack of a women’s marathon in the 1976 Montreal Olympics. Reinhart submitted that Jacqueline Hansen’s 1975 world marathon record of 2:38:19 would have placed her — had she been male — on every American Olympic squad up to the 1960 Games. Furthermore, she would have placed among the top six finishers in seven Olympic marathons — and she would have won five of those races. In future Games, Reinhart continued, each nation should enter three qualified women — those who have run under three hours — to compete in an integrated marathon. “And odds are that no official or spectator would have to wait for one of them to stagger into the stadium dead last.” This letter drew boos from some male readers.

The AAU was itself slow to recognize women’s marathon as a legitimate field of competition. As late as 1970, Dr. Nell Jackson, then head of the AAU’s women’s track and field committee, said, “If they want to run marathons, they should do them by themselves or in some other program. They don’t need to be in the AAU. We’re not concerned about those who want to run long distances. There aren’t many of them. . . . Our concern is with hundreds of little girls running cross-country rather than a few older women out for a lark.”

That year, 1970, only one woman entered the New York City marathon. Eight years later, there were 1,100 in the New York City marathon out for a lark. The AAU by then was convinced of its error. But others remained skeptical.

Hoping to demonstrate again the need for women’s marathons in the Olympics, Avon Products sponsored the Avon International Marathon in Atlanta in March 1978. It was the first international all-women marathon held in the U.S., and the largest run anywhere. Nine countries were represented, with Avon inviting and footing the bill for all foreign and many American competitors. The 186 starters included 14 of the 24 fastest women marathoners in the world.

Racing conditions tested their endurance. Instead of Atlanta’s ideal March weather, the temperature reached 75 by the 1 p.m. starting time. The morning had been quite cool, but Avon obviously wanted midday media coverage. To make things worse, most of the 13-mile loop was in direct sunlight. The hilly course had been touted as a possible setting for a new world’s record, yet it had a mile-long 250-foot climb at the nine- and 23-mile mark. The streets were bumpy and an occasional car crossed more than one runner’s path. Atlanta proved that the most progressive city in the South was in this instance a mistitle. In spite of the city’s and the sponsor’s self-congratulations, Avon was not truly top-notch.

Media coverage, at least, was excellent. ABC-TV interviewed several of the best runners for ‘‘Wide World of Sports.” Filming from a helicopter, it carried live coverage of the start. Kenny Moore wrote a first-rate account of the event for Sports Illustrated, free of the emphasis which magazines often put on women runners as attractive objects rather than as proficient athletes.

At the pre-race clinic, the first 27 runners — all invited and financed by Avon — were introduced. The 28th runner was an unknown from California named Marty Cooksey, who paid her own expenses. The next day, Cooksey, 23, won Avon in 2:46:16. Second-place winner Sarolta Monspart of Budapest was more than five minutes behind her. Monspart was the first runner from a Communist bloc country to compete in an American women’s distance race. Among the others who withstood the heat and rough course were the famous, like hometown favorite Gayle Barron — 1978 women’s winner of the Boston Marathon — who finished fifth, and the unknown, like Martha Klopfer (see sidebar), who came in 40th.

The organizers of the Avon International Marathon hoped the event would draw the attention of the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF, the governing body of running) and the International Olympic Committee to women’s long distance racing. They partially succeeded. Before the race began, Aldo Scandurra, an IAAF official, bluntly said, “This is not an international world championship. This is a race where international athletes are competing.” Seven months later, the Technical Committee of the IAAF met and passed a request that a women’s marathon be added to the IAAF-recognized World Championships.

But the 87 men on the International Olympic Committee still refuse to give the event their blessing. If women want to enter the marathon in Moscow, they’ll have to follow the model of Melpomene and jump in without anyone’s permission.

Tags

Joanne Marshall Mauldin

Joanne Marshall Mauldin, a runner and free-lance writer, is currently at work on a book about women marathoners. Her articles have appeared in Runner’s World, Running Times and Racing South.