This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 4, "Generations: Women in the South." Find more from that issue here.

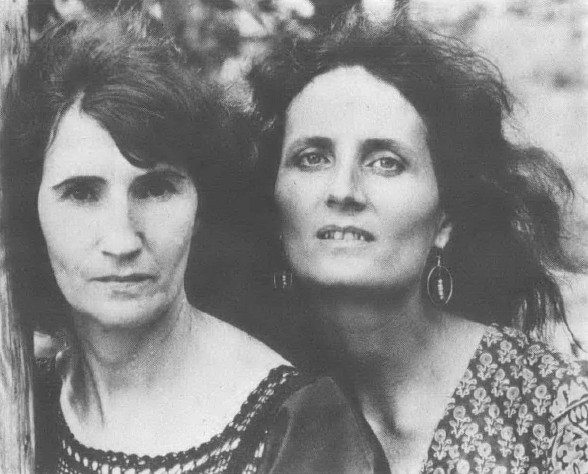

Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard have been friends for 20 years, since they met in Baltimore where Hazel sang in the all-night bars of Cozys and Blue Jays when she could get the work. They’ve been singing and playing together since 1962. You won’t hear Hazel and Alice on top 40 radio, but if you go to bluegrass and country music festivals or folk gatherings, you’re likely to hear them. Audiences love their easy manner, gutsy voices and lively music, whether it’s 10 people at a workshop or 10,000 at a folk festival. But by far their most enthusiastic fans are Southern women, who can instantly recognize and identify with the feeling behind the words as well as the sound that “puts guts into it,” as Hazel says.

It’s the combination of traditional country sounds with words of a working class or country experience that makes Alice and Hazel a unique musical duo. They have lived their music and are well-prepared to speak women’s hearts and minds, from the bottom rungs of the barstool to some new “custom-made” woman blues. Their singing relationship reflects the mix of working class “country,” with its own strong music traditions, and middle class, “city” experiences. Together Hazel and Alice have grown personally and politically, and have spoken through their music of conditions and feelings listeners could understand.

Both women credit the other’s support and encouragement as the primary reason they can create their own kind of music. “It’s an entirely different experience than I’ve ever had singing with other people,” says Hazel. “And that only comes with a certain kind of respect and love — just pure communication that you have with another person. The men I have sung with, there was always that cut-off, where you felt that you were the supporter, as opposed to being the other half of the team. But ours is a mutually supportive role. The faith and trust that Alice has had in my music has been tremendous. She was my sole support in trying to write songs, which is really putting yourself on the line.”

How did Hazel, a miner’s daughter from Montcalm, West Virginia, eighth of 11 children, meet Alice, a college-educated folksinger from Los Angeles? Hazel originally left home at 16 to work in a Virginia mill. Three years later, like countless others when mills and mines closed, she moved to Baltimore looking for work. Often singing by herself in bars and confronting the alien city, Hazel began living the life which she would sing about in later years.

“The experiences I had were incredible and I wasn’t prepared to deal with it....We were living in the slum section of the city and thrown right into the midst of it: a lot of working-class people had come from the country and a lot had got into situations they were not prepared for. I felt terribly inferior....People were always putting down my accent — even people from the South who had been to school and spoke a little better still put others down that didn’t know how to fit in. I couldn’t understand which way I was supposed to be or what I was supposed to be.”

West Virginia, Oh my home

West Virginia’s where I belong

In the dead of the night

In the still and the quiet

I slip away like a bird in flight

Back to those hills, place where I call home.

It's been years now since I lived there

And this city life’s about got the best of me

I can't remember why I left so free

What I wanted to do, what I wanted to see

But I can sure remember where I come from.

—Hazel Dickens, Rounder Records, 1976

Alice Gerrard, raised on the West Coast, married her Antioch College classmate Jeremy Foster and came to Washington in the late 1950s. In college, she was exposed to the folk revival but had been more drawn to the traditional sounds of fiddle and banjo. Like other city folk, she was interested in the instrumental sounds rather than singing — until she met Hazel.

A long list of coincidences led to Hazel and Alice’s encounter at a pickin’ party in D.C. Hazel’s brother, a black lung victim, shared an interest in traditional music with an orderly at the sanitorium where he was a patient. The orderly was Mike Seeger, bluegrass music enthusiast and high school friend of Jeremy, Alice’s husband.

When Mike, Jeremy and Alice met Hazel and her family, the music they had heard on 78’s and Library of Congress tapes came alive.

“Those were exciting times for all of us,” remembers Alice. "It was a unique kind of two-way love affair, involving friendship and closeness and learning from one another... .We learned that music and people are not separable.”

Through her new friends, Hazel began to realize that some people from the “city culture” were truly interested in her heritage and her music, in who she was and what she had to say.

“We’d been put down so much I couldn’t believe anybody was sincere about the music. When I met a lot of these people who didn’t look down on what I came from and musically what I was trying to do, I think that really sustained me.”

On the other hand, Alice met not only Hazel but a whole musical culture. “In traditional music, in country music, which is what we’re talking about,” she says, “everything is part of somebody’s experience. It’s a life music, music that really comes from people and their lives. So you can’t sing a song and not have it be part of somebody’s experience... I’m talking about a music and an orientation that basically comes from working-class women, working-class people.”

A song which profoundly reflects the impact of Hazel’s life and music on Alice is called “You Gave Me a Song.” Alice structured the song so that the verses tell Hazel’s story, but the chorus reflects what that story has meant to her own life. Alice writes simply, “Maybe I should have called this ‘Hazel’s Song’ — she was definitely on my mind when I wrote it.”

We used to be a family in our little cabin home,

Whose windows they are broken and whose chimney’s dark and cold,

But jobs were hard to find back then, it wasn't easy to survive,

So one by one we all left home to change our way of life.

Got a job in a factory on that old assembly line;

Gonna climb on up the hill and leave my past behind;

But the only climbing that I did was five flights up the stairs,

And the past I thought I'd left behind went with me everywhere.

Chorus: ’Cause you gave me a song

Of a place that I call home.

A song of then, a song of now,

A song of yet to come.

So here we are, my past and me, a-workin' in this bar;

Sing a song of broken hills and streams that once ran dear;

Sing a song of you my friend, lonely like me;

The city's taken all we have but sweet, sad memories.

But someday I'll go home again, lord it’s been a long hard road;

I’m not saying that I’ll stay but I know now if I go, I’m gonna take you with me and what you gave when I was young;

Others held me for a while but you held me all along.

—Alice Gerrard, Rounder Records, 1973

Alice’s culture opened new doors of perception for Hazel, too. She began to experience a new awareness of class, integrated with a woman’s consciousness. Looking with new eyes at the world around her, Hazel expressed a growing sense of unfairness and injustice in songs that could be called her trademark — songs about fallen women, working women, and rambling women.

“The whole way that working-class people deal with the world is different. There are a whole lot of things you let go by the wayside, things that you don’t object to because you’re afraid — and you know you can’t object because you don’t have those choices. Your livelihood depends on that paycheck every week.

“Some of these things were just earthshaking to me when I got invited to middle-class homes and became friends with people who have money. The way they relate to a situation is just so different; they have a choice — like whether or not to have a doctor, and even which doctor they may have. They have the power of money behind them. Even the simplest things, the way they buy food. They would spend more on just a little accessory to the meal than we would spend on a whole meal. It just seemed grossly unfair.”

I said I'm tired of workin' my life away

And giving somebody else all of my pay

While they get rich on the profits that I lose leaving me here with the working girl blues.

Yodel la eee

Working girl blues

I can’t even afford a new pair of shoes

While they can live in any ole penthouse they choose

And all that I’ve got is the working girl blues.

—Hazel Dickens, Rounder Records, 1976

But it wasn’t just money or class differences that aroused Hazel’s anger.

“When I first started singing in bars in Baltimore, I’d see a lot of pathetic women who would come in to pick up men. It was so confusing to me; they were so defenseless. The men would use and abuse them — and then laugh about it. Finally, I saw what was happening. It was the pot calling the kettle black!

“I realized that I could say these things if I wanted to. Up to that point, I thought somebody was going to look at me kind of strangely if I put this kind of feeling in a song. I’d never heard a song that said those things in that way.”

At the house down the way, you sneak and you pay

For her love, her body, all her shame;

Then you call yourself a man, you say you don't understand

How a woman could turn out that way.

You pull the strings, she's your plaything

You can make her or break her it's true

You abuse her, accuse her, turn around and use her

Then forsake her anytime it suits you.

Well, if she acts that way, it’s 'cause you’ve had your way

Don’t put her down, you helped put her there.

—Hazel Dickens, Rounder Records, 1973

For both Hazel and Alice, the search for identity and creative expression has been affected by relationships with husbands and, in Alice’s case, with children. Hazel’s marriage, about which she says little, lasted only a few years.

“I grew tremendously, by leaps and bounds, after getting out of that relationship,” she says.“I grew much more productive, music-wise. All my married life, I wasn’t even that involved with my music.... but then I obviously didn’t get a whole lot when I was growing up, and he didn’t either, so we were trying to get everything from each other that we didn’t get while we were growing up.”

Part of the identity search for Hazel was untangling which roles she was willing to play, just who she was as a woman. Now, through her songs, she emerges a feisty woman with a strong female response to the male country theme: ‘don’t try to tie me down, I’m just born to wander. ’ She asserts, “Now I have more of an idea of who I am and what I need and want.”

There's a whole lotta places

That my eyes are longing to see

Where there is no green cottage

No babies on my knee

And there's a whole lotta people

Just waiting to shake my hand

And you know a rambling woman's

No good for a home lovin’ man

Chorus:

Yes, I’m a rambling woman

Lord, I hope you understand '

Cause you know a rambling woman’s

No good for a home loving man

Take all that sweet talk

And give it to some other girl

Who ’ll be happy to rock your baby

And live in your kind of world

For I'm a different kind of woman

Got a different set of plans

You know a rambling woman's

No good for a home loving man.

—Hazel Dickens, Rounder Records, 1976

Alice’s life changed drastically when her husband Jeremy died in an automobile accident. Fortunately there was enough insurance money to support her and the four children, but it took time to adjust to being on her own. She grew more involved with her music, began playing more with Hazel, and helped start the magazine Bluegrass Unlimited. She remembers, more than the hardship, a growingsense of freedom in those years.

Perhaps it was this new-found freedom that allowed Alice to infuse some sense of humor into her songs about women. It seems fair to say that her early women’s songs lack the underlying indignation which Hazel’s very personal experiences brought forth. Yet in “Custom Made Woman Blues,” she touches deeply on a process known to most women:

Well, I tried to be the kind of woman you wanted me to be

And it’s not your fault that I tried to be what I thought you wanted to see

Smiling face, shining hair, clothes that I thought you’d like me to wear

Made to please and not to tease, it's the custom made woman blues.

Yes, I tried to be the kind of woman you wanted me to be

And I tried to see life your way and say all the things you'd like me to say

Loving thoughts, gentle hands, all guaranteed to keep a-hold of your man

Made to please and not to tease, it's the custom made woman blues.

Alice Gerrard, Rounder Records 1973

“It’s very important to understand what the woman’s experience has been in the past, because you can’t really move ahead without recognizing what’s come before and how to deal with it. You can’t just wipe out that whole. It’s important to recognize the attitudes that have prevailed and then try to change them. I could never write a song like “Stand By Your Man,” but if I were to sing something like “Stand By Your Man,” my responsibility would be to put the song into some kind of context that says this attitude has to be overcome, but, nevertheless, this attitude is a reflection of women’s experience.

I'm just sittin’ in this bar room

Yes, that’s whiskey that you see

And my name is Mary Johnson

And Lord, my feet are killin ’ me

I been working hard and I just stopped in

Before I head on home

And if you're thinking something different, friend,

Well you sure are thinking wrong

Chorus:

And if you think you’re reading 'want to’

In these big brown eyes of mine

Well, it’s only a reflection

Of the ‘want to’ in your mind

Now we all get lonely sometimes

And this might be your time

And you 're seeing satin pillows,

Sweet perfume, forbidden wine

And you think I’m thinking on those lines

And now and then I do

Oh, but just like you the ‘want to’ is

A thing I’d like to choose

Alice Gerrard, Rounder Records 1976

Alice eventually married her old friend Mike Seeger but later took back her maiden name. “Ours is basically a good relationship. Mike’s always been supportive and I don’t have any feeling that he would ever want to hold me back from a career....but a name can get in your way. I was always ‘Mike’s wife,’ ‘Mike’s sister,’ even ‘Pete’s daughter.’ If we were in a room full of people and someone came up to him and totally ignored me, it really bothered me. I’d say to myself, for god’s sake, you have something, too —you’re playing music independently of Mike and what you and Hazel do is really important. Yet people would relate directly to him rather than to me.”

Essentially though, Alice enjoys being married. “I like the idea very much of there being somebody in this world that knows you almost better than anybody else, that you can really expose yourself to. For me, this is very important. And I feel that Mike is just about my best friend in the world in a lot of those ways. At the same time, I go through periods where I just want to be by myself, and I don’t want to have to answer to anybody.”

She recalls one particularly bad summer when her wish for her own time conflicted with her family life. “I had a bad cough that wouldn’t go away and I couldn’t sing. All the children were there - my kids and Mike’s kids and that makes seven. And I just kept feeling like, oh God, I’m going to lock myself in a room. I did a couple of times. I’d close the door and just stay in a room upstairs for a whole day. It was really bad.”

In the early morning light I creep on down the stairs

Hush you floor, keep your squeakin’ down

And the smell of good hot coffee and the silence all around

And nothing but my thoughts, and the stirring of a song

To break the sad sweet feeling, Lord, of being all alone.

And if I'm very still I can drain this holy hour

And if I’m lucky stretch it out to two

Before the world comes crashing and down the stairs comes truth

In smiles and tears and ratty hair, and I can't find my shoes

And I don’t know, Lord, I don’t know if I can make it through

But I hope you know how much I love you

Cause I guess it ain’t showing much these days

Just old dreams of yesterday keep on getting in the way

Of picnic days and daisy chains

Of come on, let's all go into town today

Of help you make your bed and put your clothes away . . .

Well anyway, I guess I’m gonna stay

So come on now,

Your mama's gonna stay. . .

In the early morning light I creep on down the stairs....

Alice Gerrard, Rounder Records, 1976

The pervasive ideas of the women’s movement have deeply affected Hazel and Alice; they give credit to that movement, as well as to the women living their songs.

They have won many devotees the last few years, particularly among Southern women, but neither of them wants to be “boxed in,” as Hazel puts it, by the implication that they are only singing for women. Their music comes first. Hazel says, “I’ve been around and grown up with this music and if you take that away, you’ve taken the biggest part of me. Music is probably the strongest way that I express myself.”

Alice sums it up as she writes on one of their record covers, “[Our music] is the result of good friendship, lots of changes in our lives .... But the heart of the matter is really all those hours of hacking around, life confessing, amateur therapy and all the rest. Two-thirds mouth and one-third hard work, and over some time, perseverance and knowing that we love this music.”

Tags

Len Stanley

Len Stanley is an organizer with the Carolina Brown Lung Association. (1977)

Chip Hughes, a member of the Southern Exposure editorial staff, and Len Stanley have worked extensively on occupational health issues including organizing with victims of brown lung disease in North Carolina. (1976)