The Dharma Bum of Rocky Mount

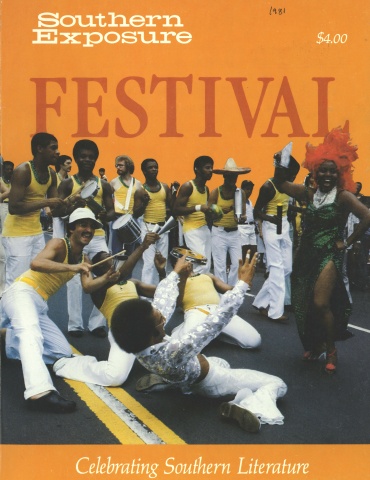

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Jack Kerouac, proclaimed on paperback covers today as “the King of the Beats,” the daddy of the Beatniks, stood out, even in a time as schizophrenic as the late 1940s and ’50s, as a mass of contradictions. Befitting his current image, he was often wild, loose, free, desperate for action. “The only people for me,” he wrote in On the Road, the book which burst the Beats into the national consciousness in 1957, “are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn burn burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’” At the same time, Kerouac spent much of his life trailing his mother, Gabrielle, across the country, taking her with him when he could, anxious to fulfill a deathbed promise to his father to care for her, though he possessed none of the financial or emotional resources necessary to do so.

From the calm and quiet of his mother’s home, Kerouac rushed to New York City for crazed day-and-night-long parties, raced across the continent to San Francisco, to Mexico City, to Denver, but always he would return, sober up, write uninterrupted and relax. And then he would leave again. His life was filled with these cycles, and the tension they produced provided much of the strength of Kerouac’s writing. Just as he moved between quiet home life and a wild party life, so did his work balance calm acceptance with paranoia, humility with great arrogance, gentleness with violence. After the second world war and until the late 1950s, Gabrielle spent much of her time in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, where her daughter — Kerouac’s sister, Nin — had settled. Kerouac visited her often, spending holidays, sometimes long months, in the small house by the Big Eason Woods. Rocky Mount was hardly a center of the Beat Movement. But there Jack Kerouac lived for parts of his most creative years. There he wrote many of his least frantic works — Visions of Gerard, Pic, much of a Buddhist volume he called Book of Prayers. There he could leave his pressure-cooker lifestyle, slow down and regain some peace. And there he was strengthened for many of the zooming cross-country journeys recorded in his most popular books, the travels and adventures that came to symbolize an alternative to mainstream materialistic America, a nation staggering from the second world war and settling into boosterism and complacency. Kerouac’s books, for their subjects and styles, became the Bibles of a movement that sought to establish new moral values for America. That movement continues today, and Kerouac’s writings (On the Road still sells 50,000 copies annually) remain an important part of it.

Jack Kerouac first visited Rocky Mount just before Christmas, 1948. He described the scene in some detail in On the Road, with the location changed to Virginia. He was completing his first-published and most traditional novel, The Town and the City, and taking classes at the New School for Social Research, when he and Gabrielle headed south for the holidays. He had written of his holiday plans to his friend Neal Cassady in California, but was surprised when Cassady suddenly arrived, unannounced, covered with the grime of several days travel, his ex-wife LuAnne Henderson and a friend still sleeping in Cassady’s new Hudson. Kerouac writes in On the Road that Cassady, “sandwich in hand, stood bowed and jumping before the big phonograph, listening to a wild bop record that I had just bought called ‘The Hunt,’ with Dexter Gordon and Warded Gray blowing their tops before a screaming audience that gave the record fantastic frenzied volume. The Southerners looked at one another and shook their heads in awe. ‘What kind of friends does Sal [Kerouac] have?’ they asked my brother. He was stumped for an answer. Southerners don’t like madness the least bit, not Dean’s [Cassady’s] kind.”

Though Kerouac hadn’t been in the South long, he needed little encouragement to leave his uncomfortable family gathering: “gaunt men and women with the old Southern soil in their eyes, talking in low, whining voices about the weather, the crops, and the general weary re capitulation of who had a baby, who got a new house, and so on.” Together, the four travelers drove non-stop to New York with some of Gabrielle’s furniture. Kerouac and Cassady returned to North Carolina 30 hours after they had left, picked up Gabrielle and took her back to New York.

In the spring of 1951, fresh from the frantic composition of On the Road — a single paragraph typed in three weeks on a 250-foot roll of teletype paper so he would not have to waste time changing pages — Kerouac again relaxed in Rocky Mount, with a book supply that included Dostoevski, Proust, Lawrence, Faulkner, Gorky, Whitman, Dickinson, Yeats and more. In the summer of 1952, he returned to Rocky Mount after a tense visit with William Burroughs in Mexico City, where Kerouac had completed Dr. Sax, his recreation of a childhood fantasy. His manner of composition demanded recuperation, and he often found it in North Carolina.

Kerouac’s sister and her husband, Paul Blake, lived in a house just outside of town, near what is now Langley Cross Roads. It was — and remains — an isolated place. On the back of the house stands a porch — now enclosed, but then walled by screens — which Kerouac converted to a bedroom from Christmas, 1955, until April, 1956. Shortly before that, he had met poet Gary Snyder and had become imbued with Snyder’s love of the outdoors. He stretched out a sleeping bag on this porch and slept there through the winter months. Twice daily he wandered into the Big Eason Woods behind the house and meditated cross-legged on matted straw, beneath twin pine trees. As Kerouac de scribes the scene in Dharma Bums, the area was beautiful: “The ground was covered with moonlit frost. The old cemetery down the road gleamed in the frost. The roofs of nearby farmhouses were like white panels of snow. I went through the cottonfield rows followed by Bob, a big bird dog. ... We were all absolutely quiet. The entire moony countryside was frosty silent, not even the little tick of rabbits or coons anywhere. An absolute cold blessed silence. Maybe a dog barking five miles away toward Sandy Cross. Just the faintest, faintest sound of big trucks rolling out the night on 301, about twelve miles away, and of course the distant occasional Diesel baugh of the Atlantic Coast Line passenger and freight trains going north and south to New York and Florida. A blessed night.”

Down the street from the Blake-Kerouac home stood two country stores, and they remain today, both run by members of the Langley family. In the stores, “the old boys there sitting among bamboo poles and molasses barrels” would ask him what he was doing in the woods. Studying and sleeping, he’d say. When he talked of his Buddhist studies, they suggested that he return to the religion he was born with. Many of those same “tobacco-chewing stickwhittlers” still sit in the stores, but now Kerouac himself is a subject they are asked about. In the last decade, dozens of Kerouac fans have visited the area, looking for a Beat memorial, Kerouac’s old haunts, hoping to hear anecdotes of him. They’re usually disappointed. Those in the store nod and chew, chew and nod. Yep, they knew him, they say. Nope, he didn’t do much, they say, just minded his own business. Nope, they don’t remember ever selling him any wine, though he wrote of long Rocky Mount nights with bottles of wine. The landlady of Kerouac’s house, his former next door neighbor, doesn’t add much more: Kerouac had wandered through her backyard often, heading for the stores. He seemed odd at the time, she says, barefoot, unshaven, usually wearing a plaid shirt, writing and sitting in the woods, never working a “real” job. “Today, of course,” she smiles, “that wouldn’t seem unusual. He was just ahead of his time.” When the book mobile from the library first came through with On the Road, she says, everyone felt proud that he had been published. She admits, though, that she never read it all.

When it was first published, Kerouac’s writing shocked many. He rejected materialism, politics, most racial stereotypes, the quest for suburban bliss, Western religions, pop music, even rationality. He promoted spontaneity, Buddhism, mysticism, expressed emotions, jazz and his alternating cycles of asceticism and wild overindulgence in alcohol and drugs. He was alternately in love with the world, and overwhelmed by its immense pain.

American prose style was then heavily influenced by Hemingway’s short, crisp, journalistic sentences. Kerouac’s sentences flowed in rambling discourse, each filled with a dozen scattered thoughts, sometimes interrupted by parenthetical phrases that filled a page. His goal was to find a natural style to present people and scenes as they came to him, as a storyteller would present them, and not just in stiff chronological order. His extensive notes and even more extensive memory (Allen Ginsberg once called him “The Great Rememberer”) allowed him to write as if he were experiencing events that he instantly put down on paper, and he included many of the inconsistencies, seemingly unnecessary details and pointless conversations in which we all fill our days. To many readers he brought great life to apparent trivialities. To early critics, his style was both shallow and indulgent, and he was widely attacked, not just for his own work, but as a representative of all those who tried to stretch the bounds of writing in the late 1940s and early ’50s.

After the publication of On the Road, Kerouac became a cult figure and a hated stereotype. Wherever he went he found that people had already formed opinions of him, had branded him and expected him to live up to their images. Ultimately his ability to write collapsed when Kerouac’s fame prevented him from escaping to the anonymity of small towns or unknown cities. The only escape he found was into booze, and his already great thirst quickly became a strong case of alcoholism. His admirers didn’t help. His hard-drinking reputation encouraged them, and they lined up to ply the great man with alcohol. One experience in North Carolina was typical: in the early ’60s, Kerouac was hitching along the east coast, one of his last hitchhiking experiences, when he was picked up by a University of North Carolina student. Excited by his find, the driver took Kerouac back to Chapel Hill, where he was paraded through every bar on Franklin Street by students disappointed when he grew too drunk to discourse on literature. He could no longer retreat, as he did in Rocky Mount, and because of that he could no longer write. “Let me tell you,” he once said, “a true writer should be an observer and not go around being observed, like Mailer and Ginsberg. Observing — that’s the duty and oath of a writer.” He died, lonely and frustrated, hiding from the public, in 1969. He was 47 years old.

Today, though Kerouac’s books still demand an uncommon patience, their energy remains strong, their rhythms often equal to good jazz riffs, and his characters are generally endearing, even sweet. While he wrote extensively of his friends and their adventures, his works concentrate as well on truck drivers who gave him lifts, buddies who worked on the railroad with him, waitresses in restaurants. The community that he described was a very broad one, broader than that presented by most of his fellow writers of the time, and included the “stickwhittlers” at the corner stores in Rocky Mount as well as hipsters in hot jazz clubs. Jack Kerouac had a sense of people — of their lives and their language — that showed a great respect, whatever their class or race, for their histories and for their voices. This didn’t develop because of his time in Rocky Mount — he found it early growing up in Lowell, Massachusetts — but it was the kind of respect that is common to the best of Southern writers, and that perhaps was nurtured for him in the South.

In the South he could relax, catch his breath, unwind before returning to the cauldron. The peace of Rocky Mount kept him from falling too much into either of his primary emotions: drunken frenzy or pounding despair. It served for Kerouac, as it has for so many writers, as a way of keeping balance.

Tags

Steve Hoffius

Stephen Hoffius is a free-lance writer in Charleston, South Carolina. For a year he edited the state newsletter of the Palmetto Alliance. (1984)

Steve Hoffius is a free-lance writer in Charleston, and a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1979)

Steve Hoffius is a Charleston, SC, bookseller and free-lance writer. (1977)

Steve Hoffius, now living in Durham, N.C., co-edited Carologue: access to north carolina and is on the staff of Southern Voices. (1975)